If MI5 had a Cold War file on you – paper in those happy days – it didn’t mean they thought you were a spy. Nor even that you were especially interesting. Files were a means of storing and retrieving information. They could be general subject files or personal files (PFs) relating to individuals. Some PF holders were secretly investigated, but many were merely monitored – i.e. information about them was collated until it was clear there was no need for further investigation.

Following their seizure of power in Russia in 1917, the avowed mission of the Soviet government was to foment worldwide revolution in order to impose communism. MI5 was tasked with investigating, monitoring and – within the law – preventing subversion. This was defined as ‘activities designed to undermine or overthrow parliamentary democracy by political, violent or industrial means’. By the 1990s, when the Cold War was rashly assumed to have ended, many on the left were convinced that MI5 had abused its powers by investigating and persecuting patriotic trades unionists, honest journalists, truth-seeking academics, democratic freedom fighters and honourable members of parliament.

InRed List, David Caute – scholar, author, journalist and renowned man of the left (but no communist) – trawls MI5 files released to the National Archive, citing references to such diverse figures as the two Amises, Kingsley and Martin, Harriet Harman, Benjamin Britten, Jacob Bronowski, Paul Robeson, Doris Lessing, Michael Foot and many others. He seeks examples of MI5 exceeding its brief by investigating those who posed no threat to national security but were merely exercising their civil liberties. Too often, he concludes, MI5 ‘pursued’ people simply for being ‘unafraid to express dissenting views of the national interest’, assuming them guilty ‘by association, real or imagined, with the Communist party and the Soviet Union’.

There are, indeed, such examples, but Caute is too true to what he finds for his broader case to stand. The overwhelming impression of this compilation of assumed injustices is that MI5 were right to investigate or (more often) monitor those they identified, and right to close files on them when they found no threat to national security.

Most of the files are boring, largely comprising press cuttings, attendance lists, police reports, gossip from the (bugged) headquarters of the Communist party and the opinions of colleagues. The truth which emerges is that many of these people were initially thought to be worth looking at because they were active members of the Communist party, or sympathetic to it, and were in positions with the potential to threaten national security. In fact, they mostly didn’t – either because they never intended to, or because they lost faith in the Soviet Union, or simply changed their minds.

There were exceptions. The publisher James MacGibbon was an active communist, who spied for the Russians while serving in military intelligence during the second world war. He was investigated and interviewed but – as often happened – never charged. Without a confession there was no evidence that could be used in court.

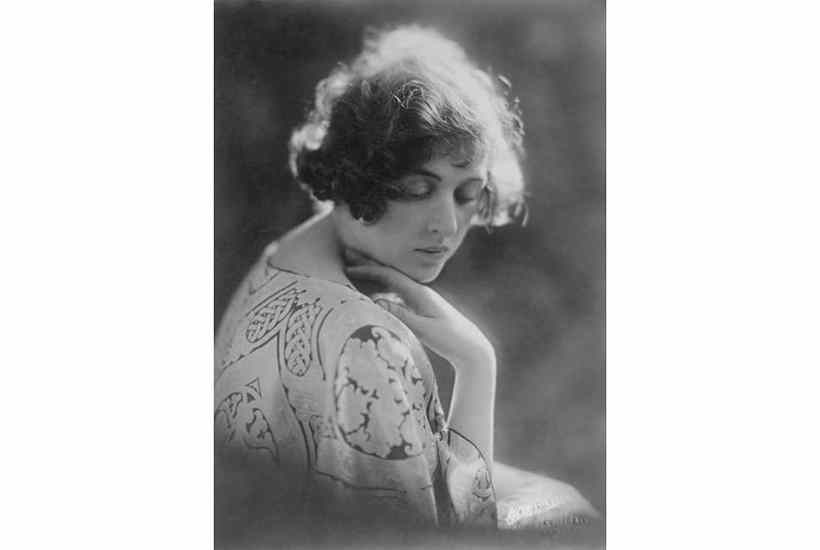

More colourful was the glamorous sculptor Clare Sheridan, Churchill’s cousin, who adopted the Soviet cause in 1920. Although never a Communist party member she got herself to Russia, lived in the Kremlin and sculpted busts of Soviet leaders, including Trotsky, Zinoviev, Dzerzhinsky and Lenin himself. She subsequently had a relationship with the pro-communist Charlie Chaplin and survived attempted rape by Mussolini. She travelled the world broadcasting anti-British views and was monitored by MI5 until they concluded that she was neither a spy nor a security threat but merely ‘extraordinarily indiscreet’, and had ‘a passion for international mischief-making’. She was later reconciled with her cousin, spent time at Chartwell during the second world war and converted to Catholicism.

Caute devotes considerable attention to relations between MI5 and the BBC, which used to involve a discreet vetting arrangement intended to prevent infiltration by communists and their sympathisers. He describes it as ‘MI5’s method of leaning rather than stifling’, and makes clear his disapproval. Ditto the informal manipulations by which academics seen as subversive were sometimes diverted from the posts they desired. Caute seems to give credence to Harold Wilson’s and Tony Benn’s fantasies that they were bugged and burgled by MI5. With regard to CND, he argues that MI5 saw it as its ‘task to prove the infiltration or domination… by the Communist party’. In fact, MI5 concluded the opposite: although CND was a target for communist infiltration, they judged it a broad-based popular movement that was not subversive.

Caute’s file survey reads as if he is hoping for more abuse and error than he finds. But he is too fair-minded, and too good a historian, to allow himself to be overruled by his political inclinations. As he concludes, in the UK ‘dissident intellectuals were not normally deprived of their passports and the right to travel, and their books were not purged by public and university libraries’. MI5’s assessments of threat were – he implies, but does not say – generally well-balanced.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in