A veteran Tory MP, who I’ve known for almost 30 years, just laid into me – and my colleagues in much of the media – for allegedly exaggerating the seriousness of how Covid laws were systematically broken in 10 Downing Street.

He hadn’t read Sue Gray’s report into the rule-breaking parties and did not attend the PM’s statement on her findings. He has already decided that all is for the best in Boris Johnson’s best of all possible worlds.

His decision to ignore Gray’s report is not what most voters would expect from their elected representatives. What many would see as his negligence is all the greater because in my lifetime there has never been a report into misconduct at the heart of government as damaging as Gray’s.

The respected official gives a dizzying number of examples of senior and junior officials and ministers – including the most senior official, Simon Case, and the prime minister – behaving as though laws they formulated to protect the NHS and save lives didn’t apply to them.

Here are just a few manifestations of the rottenness at the heart of government. The government’s former director-general of propriety and ethics brought a karaoke machine to one party. Another especially raucous party did not end till after 4 a.m., on the day of Prince Philip’s funeral. At another, lasting several hours, ‘there was excessive alcohol consumption by some’, ‘one individual was sick’, and ‘there was a minor altercation between two individuals’. And after yet another, a cleaner, on the morning after, noted wine had been spilled on a wall and all over photocopy paper.

Gray concludes that the gatherings were ‘not in line with Covid guidance’, there were ‘failures of leadership and judgment in No. 10 and the Cabinet Office’, and that ‘the senior leadership at the centre, both political and official, must bear responsibility for this [rule-breaking] culture’.

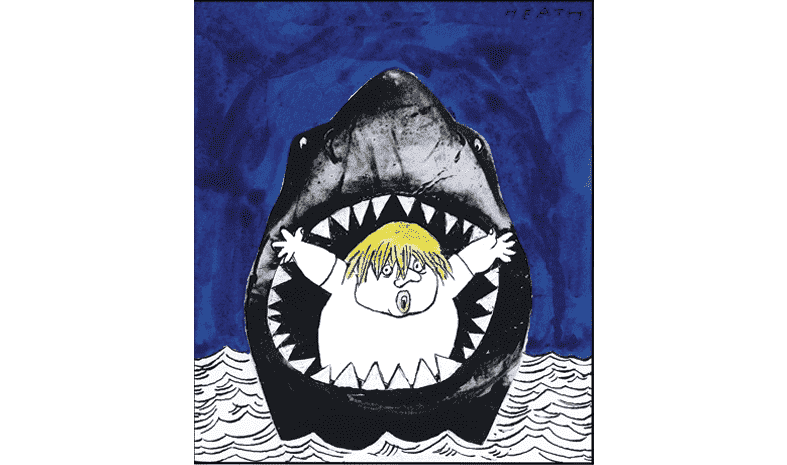

The PM’s excuse today is that he never stayed at the parties long enough to see them descending into drunken, chaotic revels. So although he has been fined for attending his own birthday party, he insists his hands are clean, so to speak.

Johnson’s may well be seen as an eccentric defence since the laws he wrote were clear that all parties were banned, whether at lunchtime or in the early hours. And he may not have been drunk and disorderly at the Downing Street dos, as others were, but drunkenness – while inappropriate in the workplace, as Gray needlessly points out – was not the test of whether the law was being broken.

What is perhaps most damaging for the prime minister and for the cabinet secretary is that Gray was made aware of ‘multiple examples of a lack of respect [for] and poor treatment of security and cleaning staff’.

The implication is that they were uncomfortable about the parties, but did not have the authority to break them up. Which points to the huge unspoken question in every line of Gray’s opus: why didn’t those with the authority to break up or ban the illegal parties, namely the cabinet secretary Case and the prime minister, even once break up a single one?

And given the revealed rottenness of the culture at the apex of the government, why is this failure not a resigning issue for either the cabinet secretary or the prime minister?

Gray is explicit that although everyone who attended the parties was at fault, ‘senior leadership at the centre, both political and official, must bear responsibility’, because ‘some of the more junior civil servants believed that their involvement in some of these events was permitted given the attendance of senior leaders’.

The prime minister’s principal private secretary Martin Reynolds said in a WhatsApp after the bring-your-own-booze garden party: ‘We seem to have got away with it’.

The point about Reynolds is that as the PM’s most trusted adviser, when he sent out emails to staff inviting them to parties, he was seen by those officials as speaking with the PM’s authority and knowledge – whether or not Reynolds actually consulted the PM not. As a former senior adviser to another Tory PM told me, ‘that’s how the system works’.

So has the PM ‘got away with it’? In the weeks ahead that will be decided by Tory MPs – who alone have the power to force him out. And if the anger of the one who accosted me just now is a guide, some have forgiven him without troubling themselves with the facts.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

This article originally appeared on Robert Peston's ITV blog

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in