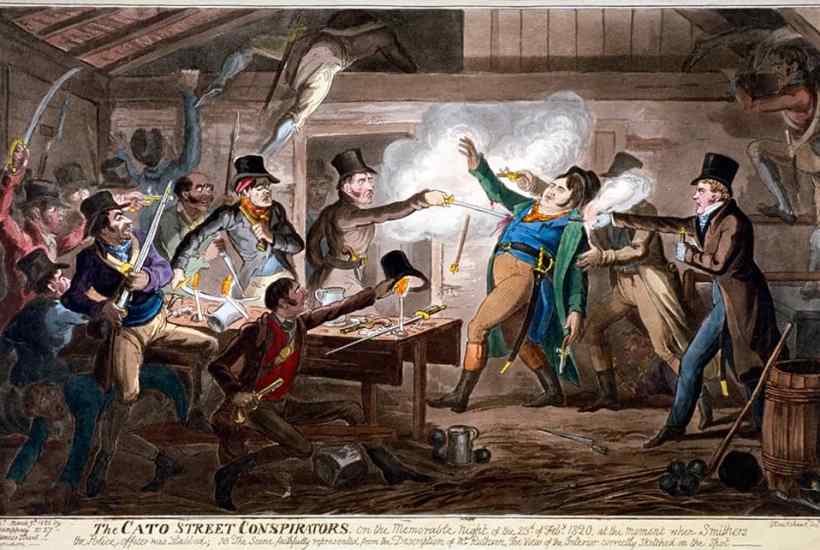

Almost half of the terrorists hadn’t even turned up. Still, on the night of 23 February 1820, 25 men, including a butcher, several shoemakers and a cabinet maker, met in a hayloft on Cato Street, just off the Edgware Road in central London. Led by the semi-respectable son of a tenant farmer, Arthur Thistlewood, their plan was to assassinate the prime minister Lord Liverpool and his cabinet, who were thought to be dining together at the Grosvenor Square mansion of Lord Harrowby, the president of the privy council.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in