‘Whenever you see a character in a novel, let alone a biography or history book, reduced and neatened into three adjectives, always distrust that description.’ So says the protagonist of Julian Barnes’s latest novel, the poised, droll, epigrammatic Elizabeth Finch, who is loosely modelled on his late friend and fellow Booker Prize-winner Anita Brookner. A lecturer delivering an adult education course on Culture and Civilisation, an exercise she considers ‘rigorous fun’, she introduces her students to figures such as Goethe and Epictetus. Her talks, designed to make them question what they think they know about the past, are peppered with little provocations: ‘We should always distinguish between mutual passion and shared monomania’, for instance; and ‘I happened to be reading Hitler’s Table Talk the other evening.’

We’re exposed to Elizabeth’s idiosyncrasies through the recollections of Neil, one of her students. A former actor, he’s frank about his evasiveness and his embarrassing inability to finish any project, as well as his preoccupation with thoughts of frailty (faith’s, truth’s, his own). Elizabeth, or EF as he and his classmates call her behind her back, intrigues and then obsesses him.

As EF offers her crisply grammatical pronouncements on the legend of St George or the 19th-century impact of rail travel, we may not be wholly convinced of the vaunted originality of her ideas and elegance of her teaching. But for Neil she’s an ‘advisory thunderbolt’, creating starbursts in his head. She jolts him into awareness that history is ‘not something inert and comatose’ but instead ‘active, effervescent, at times volcanic’, and boosts his self-worth when she tells him that acting is ‘the perfect example of artificiality producing authenticity’. On an impulse he asks her out to lunch, and so begins a 20-year extension of that Culture and Civilisation course, which results in his becoming the custodian of her library and papers – and of her myth.

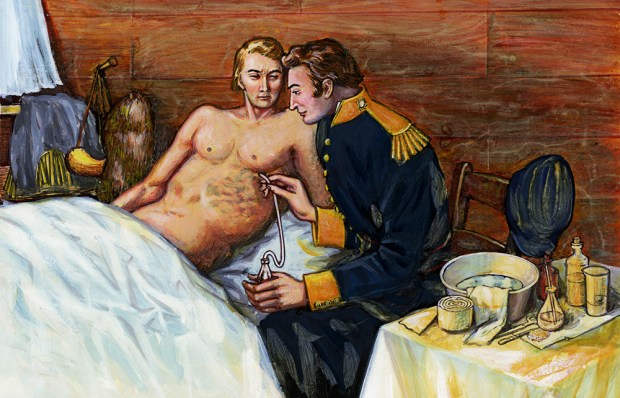

For the first 70 pages Elizabeth Finch appears to be a twinkly character study, a portrait of the sort of noble teacher who inspires poetic and political awakenings. Like most of Barnes’s recent work, it exhibits the wryness of the late middle-aged. The prose has his customary wit and precision. But then it becomes something else. EF teaches her charges about Julian the Apostate, the last pagan emperor of Rome, who in her phrase ‘attempted to turn back the disastrous floodtide of Christianity’. This, Neil gathers, was ‘the moment history went wrong’, and many years later he decides he owes it to her to produce an account of Julian.

It’s brave of Barnes to make the book’s middle third a dry student dissertation (with chatty asides) on the ups and downs of Julian’s reputation. Neil shows how the Apostate became a bogeyman for Christian polemicists, and looks at his depiction by writers such as Milton, Voltaire and Ibsen. If one accepts the more generous interpretations, he comes across as a lost leader, a sober and judicious reformer. Had he not died at 31 of a wound sustained in battle, he might have averted a multitude of ills: religious and racial intolerance and the stifling of science and scholarship.

Barnes’s novels are essayistic, with a tendency to skirt around a subject instead of focusing on it, and as Neil, having for once finished his homework, ponders other ways to pay tribute to EF, he keeps circling back to her concern about the common, ugly habit of ‘getting our history wrong’. This means two things: taking the wrong fork in the road, and using mangled notions about the past to justify reckless manoeuvres in the present. Might Neil, an eager Europhile, be thinking of some recent event rather than one from the declining years of the Roman empire? Why does he latch on to a passage in EF’s lecture notes that dwells on Britain’s record of not ‘learning from otherness’? What prompts him to relate so keenly to the Apostate’s horror at the Christian upstarts and their ‘refusal to acknowledge experts’?

‘This is not my story,’ Neil insists. A reader with an eye for self-reflexive humour may wonder whose story it is, when (ahem) Julian is portrayed as a lofty, scholarly, fair-minded author, whose central text is a three-part work – a man devoid of personal vanity, popular in France, though a bit too sophisticated to be warmly received in his own country.

But Barnes has an escapologist’s nimbleness, and Elizabeth Finch only toys with the possibility of being an anti-Brexit screed or an unblushing selfie. It’s more concerned with disappointment, hidden desires, mis-understandings and the irrecoverability of the past. Each is familiar territory for Barnes, yet here their treatment feels slight. At one point Neil accuses himself of ‘novelettish banality’, and the phrase lingers in the mind uncomfortably.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in