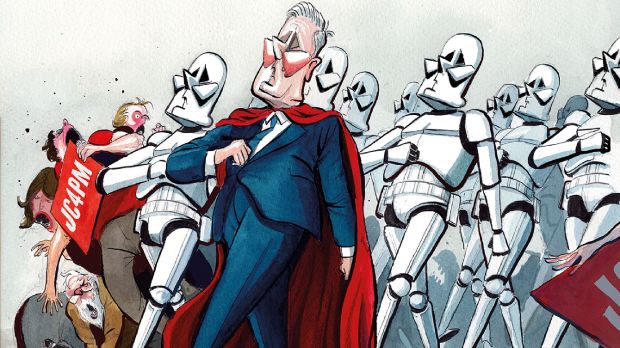

If you want to understand how Russians see the world, it helps to watch Russian TV. The Kremlin’s control over the airwaves permeates every part of Russia’s television schedules. There are no longer soaps or series during waking hours, just relentless TV shows about Russia’s place in the world. The popular and execrable ‘news’ discussion show 60 Minutes now often lasts two to three hours. It is as if EastEnders and Coronation Street were replaced with 200 minutes of state propaganda.

Such shows depict Russia’s horrific assault on Ukrainian towns, cities and people as a special military operation. They are punctuated with clips of Vladimir Putin celebrating a successful and pre-emptive mission to free Donbas from genocidal Ukrainian butchers. Russians and non-Russians alike see the human misery and detritus of an unprovoked invasion by a fascistic army – except Russians think that army belongs to Ukraine.

Clips and quotes from Putin’s interviews are repeated across Russian media for days on end. Vesti Nedeli, a flagship weekly news roundup show fronted by propagandist-in-chief Dmitrii Kiselev, is a good example of the genre. It intersperses Putin’s wild accusations with stories about Pentagon bioweapon networks in Ukraine, Nazis torturing children, economic collapse in the West, efforts to cancel Russia, and transgenderism.

Despite clear evidence the invasion has stalled, the mood on Kremlin TV is assured. According to Vesti Nedeli’s military correspondent and army mouthpiece, Evgenii Poddubny, it is Ukrainian fighters that are deserting, not Russians, and it is Ukrainian supplies and equipment being destroyed, not Russia’s. By way of evidence of Russian success, the camera zooms in on the corpse of a young Ukrainian soldier. This brutalising image is followed by efforts to humanise the Russian invaders, one of whom starts his interview by telling his wife that he loves her.

Lots of the programming is designed to reinforce the image of Russians rescuing Ukraine from Nazi tyranny. On Tuesday, news channel Rossiya-24 was broadcasting stories about Nazi battalions fleeing the wreckage of Mariupol dressed as women and using civilians as shields. The report suggested that the benevolent Russian army was refraining from attacking with full force to protect civilians. Viewers were also shown tales of Europeans protesting food price rises, snippets from Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene’s criticism of US support for Ukraine, and stories insinuating that the USA developed Covid-19. Russian news paints a picture of global misery that not only justifies the ‘special military operation’ but also tells Russians that the country’s economic woes aren’t the government’s fault and that everything is far worse abroad.

There is also plenty of unconvincing footage of impoverished Ukrainian villagers welcoming considerate soldiers bedecked in St George’s ribbons (a symbol of the second world war). In one video, soldiers decamp to a nearby field before retaliating, ostensibly so as not to give the Ukrainian army an excuse to shell populated areas. The viewer learns that this same field was the site of major battles between the Wehrmacht and Red Army in the second world war and that now, Russian soldiers, descendants of the heroes of that war, are back to liberate Kyiv from Nazis once again.

Flicking through some of the other channels, historical analogies and second world war references are a constant among a vast range of claims about what is really going on in Ukraine. There are comparisons made between modern Russophobia and Nazi anti-Semitism. Documentaries about western-sponsored terrorism in Crimea are shown alongside videos about Ukrainian shrines to Adolf Hitler.

But while these stories may seem confusing or even confused, they are better understood as forming a part of Russian popular historical myth. In this alternate reality, Russia is under attack from the West, as so often in its history, and must either fight back, like in the second world war, or be destroyed like the USSR. Russian audiences are led to believe that history will repeat itself, either as triumph or as tragedy. Millions of Russians believe that Nazis have ruled Ukraine for years, and have been crucifying Russian children, burning people alive and pursuing a genocide in Donbas.

One of the first things Putin blew up after invading Ukraine was the Kyiv TV tower. It echoed his first moves on being elected president some 22 years ago, when he shut down and took over independent television. And like a terrorist recruiter, the Russian state and its media puppets have been luring audiences down a path of radicalisation for years with increasingly extreme tales.

If you look at Russian polls, it appears they have succeeded. State television has flaunted the latest Russian Public Opinion Research Center surveys showing that more than three-quarters of Russians approve of Putin’s actions and that almost 80 per cent trust their president. The same poll shows that 62 per cent trust federal television, up 16 points since the start of the war. Only 22 per cent trust social media. Of course, these figures are massaged but they are not imagined and, in cases like these, they also encourage doubters – those who worry that maybe the pro-war Z symbol looks a lot like a swastika – to keep quiet because nobody else thinks like they do.

There are other, darker encouragements to keep quiet, such as Putin’s carefully chosen comments about the need to cleanse society of national traitors, a deliberate invocation of Stalinist language to conjure the memory of the repressions and murders of that age. As in the 1930s, baseless allegations of treachery are being thrown around. Marina Ovsyannikova, who interrupted state TV with an anti-war protest, has now been accused by her boss of being a British spy. In this atmosphere it is frightening – and illegal – to tell the truth. I have seen plenty of people arguing that those who support the invasion are simply brainwashed or terrified. How else to explain videos and stories of Russian mothers refusing to help or even believe their captured sons?

This is a comforting explanation, but it is not sufficient. I lived in Moscow when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014. The intensity and effectiveness of the propaganda led me to leave Russia (and conduct PhD research into its state media). I witnessed how, despite the insanity of the Kremlin’s narratives, despite the accessibility of BBC Russian and independent media, despite the option to travel to Ukraine, many Russians really do want to believe the government’s narrative. In particular, I recall when Russian fighters shot down passenger jet MH17, killing 298. I remember discussing this crime with two highly educated friends and my shock when they repeated the Kremlin’s unhinged stories about imagined Spanish air traffic controllers who knew the real truth, about Ukraine thinking it was Putin’s plane, about the plane being pre-loaded with dead bodies. They must have known they were spouting nonsense, but they chose to believe it.

But before we scapegoat the Russian mentality or ‘soul’, it is worth noting one of these erstwhile friends was British. Propaganda works because of general context and individual choices, not genetic predisposition. Even with the recent censorship of social media, most Russians have internet coverage and access to VPNs.

If Russians wanted to look for alternative realities elsewhere, they could. They could choose to believe and to spread online the unpalatable truth of what their army is doing to Ukraine. They could choose to turn on the Kremlin and its own warped reality. But many ordinary Russians have made a choice to believe a narrative where they are the heroes or the victims, but never the perpetrators.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in