Well, at least Covid is over. No sooner had Vladimir Putin’s tanks rolled into Ukraine than the UK’s Covid advisory group Sage disbanded. The same effect was felt in the US, where the outbreak of war in Europe led to the immediate, unlamented disappearance of Dr Anthony Fauci. After two years on primetime, suddenly the good doctor was nowhere to be seen. Covid already seems so very last season.

The ‘climate emergency’ likewise seems to have drifted away. For years, whenever the world was facing no more proximate emergency, every politician from the Scottish parliament upwards insisted that we were all doomed and heading to hellfire. Such thinking captured most developed governments and terrified a generation of young people with an insistence that we had, at various times, only a decade, a month or a minute to save ourselves.

Now those folks have more than piped down. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has actually made some of them about-turn. Now that a real crisis is occurring in the neighbourhood, even Germany’s Green party has realised that you can’t farm out your ethical energy dilemmas to another country. Germany was all set to be reliant on Russian gas while pretending that it was as green as green could be. All it achieved was to hobble itself and outsource its energy future to a madman.

A similar awakening appears to be occurring here in the UK. Only weeks ago Boris Johnson could be found blithering on about net zero being the priority of his Conservative government. Now he is starting to recognise that abandoning the most effective forms of energy while relying on the least is not a good policy. It took a war to persuade him of this. ‘You’ve got to reflect on the reality that there is a crunch on at the moment,’ Johnson manfully conceded this week.

I do not wish to mock. Or at least not to mock excessively. Rather I mention it because it highlights something deeper. As I have commented before, it has seemed to me in recent years that our era has a tendency, even perhaps a desire, to lurch from disaster to disaster. The disaster of the current moment is Putin. Before that it was Covid. Before that it was Green. I can’t remember what it was before that. Racism? Brexit perhaps? Somewhere in the middle there were parties. But society has developed an appetite for focusing on one thing at a time, putting all our attention on it, like the Eye of Sauron, and then moving on. In the process it is easy to affix ourselves to cause after cause in search of meaning. It is also possible to fall prey to cynicism, not to mention hopelessness.

As it happens, I was thinking about this recently while in Savannah, Georgia, helping to launch a new liberal arts college called Ralston College which is opening for students later this year. The aim is to give them the sort of education that used to be regarded as a proper education. There will be teaching of the classics and the great works of the western canon, and an understanding of civilisation and the riches it has produced. At these moments such efforts can erroneously seem inadequate. One professor told me that a student of his had recently said that she wished to go to Ukraine to fight. It turned out her parents had experienced Russians tanks before, and she wanted to do something to help. In reality a student in the humanities, untrained in the arts of war, is little help against an invading horde.

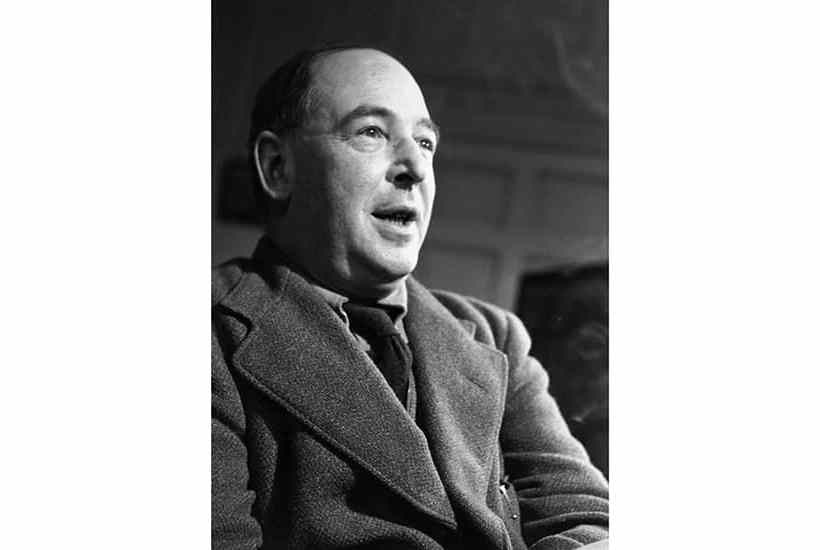

And here a certain hopelessness can creep in. Perhaps it already has for many people. But I was suddenly reminded of a sermon C.S. Lewis gave at the university church in Oxford in the autumn of 1939. I mention it not because I think we are in a remotely similar position to our situation then, nor am I one of those many people who believe that humanity seems endlessly doomed to replay the 1930s. I mention it only because the content of what Lewis said in ‘Learning in War-Time’ seems appropriate to this moment.

For one of the many points Lewis made is a point I have occasionally tried more inadequately to convey, which is an invitation not to put off what we should be doing simply because there is catastrophe in the world. As Lewis said: ‘Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice… If men had postponed the search for knowledge and beauty until they were secure, the search would never have begun.’ Life, in other words, has never been ‘normal’, and even those periods of history that we imagine to have been so show themselves, on closer inspection, to have been full of alarms of their own. ‘Plausible reasons have never been lacking for putting off all merely cultural activities until some imminent danger has been averted or some crying injustice put right,’ said Lewis.

Our species distinguishes itself by ignoring those plausible reasons. The insects have chosen their way, and have their rewards, says Lewis. But it is not our way. ‘Men are different. They propound mathematical theorems in beleaguered cities, conduct metaphysical arguments in condemned cells, make jokes on scaffolds, discuss the last new poem while advancing to the walls of Quebec and comb their hair at Thermopylae. This is not panache. It is our nature.’

While Lewis seems to me to be correct, that nature he describes could in fact be changed. It could be changed if that nature was widely perceived – and taught – to be wrong. A dominant voice of our era says that everything else must be put off until this season’s crying injustice or wrong is addressed, until inequality is fixed, justice reigns every-where, or the temperature of the planet is made forever clement. I do not underestimate the danger or misery of what is happening in Ukraine. But the history of the past few years should have shown us, if nothing else has, that this is what human life is like – a lurching from one disaster to another. The catastrophes are endless and come in succession. But they cannot define our lives any more than they absolutely have to. It is what we choose to do in the moments in between catastrophes that counts.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in