Why are so many people in such a muddle over the word ‘woman’? Sadly, a share of the blame falls on women’s studies and gender studies. I should know: this has been my academic field for over a decade.

As a teaching assistant, I remember repeating the phrase ‘there is more difference among the sexes than between the sexes’ in front of a group of students, without properly thinking it through. A sociology of gender professor taught me that, and I absorbed it like a sponge. It was only upon reflection that I realised the consequences of denying sex differences. Most of my cohort never changed their minds.

During the confirmation hearings this week of Ketanji Brown Jackson, who could become the first black female Supreme Court judge in the United States, Jackson was asked to define the word woman. She refused, saying: ‘I am not a biologist.’

Just a few days earlier, a fierce debate opened up in the US regarding the inclusion of male athletes in female sports, following the high-profile victory of trans swimmer Lia Thomas over other women in the National Collegiate Athletic Association swimming championship.

In Britain, some politicians are at last seeing sense on the gender issue. At PMQs this week, Boris Johnson said: ‘When it comes to distinguishing between a man and a woman, the basic facts of biology remain overwhelmingly important.’ But plenty of his colleagues in Parliament don’t appear to agree.

The subject I have spent years studying carries a great deal of responsibility for the reason why progressive politicians like Labour’s Anneliese Dodds, the shadow minister for women and equalities, become unstuck when it comes to the word ‘woman’. During an appearance on International Women’s Day, of all days, Dodds was asked to define what the five-letter word meant: ‘I think it does depend what the context is surely,’ she said. While Dodds didn’t answer the question, her response was revealing.

Why? Because focusing on ‘context’ is the way academics in my field try to deal with difficult implications of their views on gender. In Women’s Realities, Women’s Choices, a foundational text in women’s studies published in 1983, the Hunter College Women’s Studies collective pondered:

‘Do biological characteristics give us a definition of ‘woman’? The answer is not as simple as we might expect it to be. Biological and physical attributes are frequently used in defining ‘woman.’ Scientists, who are primarily men, reflect the biases of the culture. Average differences between males and females in physical behavioural attributes, such as physical strength and height are frequently cited. An average, however, is a statistical concept. The range of differences within any one sex is greater than it is the average differences between the sexes.’

While this line of thinking – which blends the barriers between the sexes – started off as a campus pursuit, it has now oozed out into the mainstream – as Dodds’ confusion shows all too clearly. Women’s studies sought to transform and revolutionise academia by applying scientific rigour to the concept that ‘the personal is political.’ Given the hostile reception to the movement at the time, this could only be achieved by squashing the idea that female biology – the ability to carry and feed children – determined our destiny.

The idea was that if a patriarchal system treats women as inherently inferior to men then it made sense to ferociously advocate that both sexes are, in fact, equal in almost every respect. So biology became an enemy that would naturally come back to haunt us. In this pursuit for equality, what we all surely know to be true – that humans are differentiated by sex on a chromosomal level – was left out of the picture.

Yet while progressive politicians – and gender studies theorists – might like to imagine there is no downside to this approach, they are wrong. After all, pretending that male and female bodies are no different from each other risks causing no end of problems: women suffering from a heart attack might be dismissed as having anxiety and stress. Why? Because the medical establishment has long been dominated by men. It seems natural that male doctors are more likely to educate students on male bodies and ‘male symptoms’ for many ailments. If women and men are viewed as one and the same, these differences can get ignored.

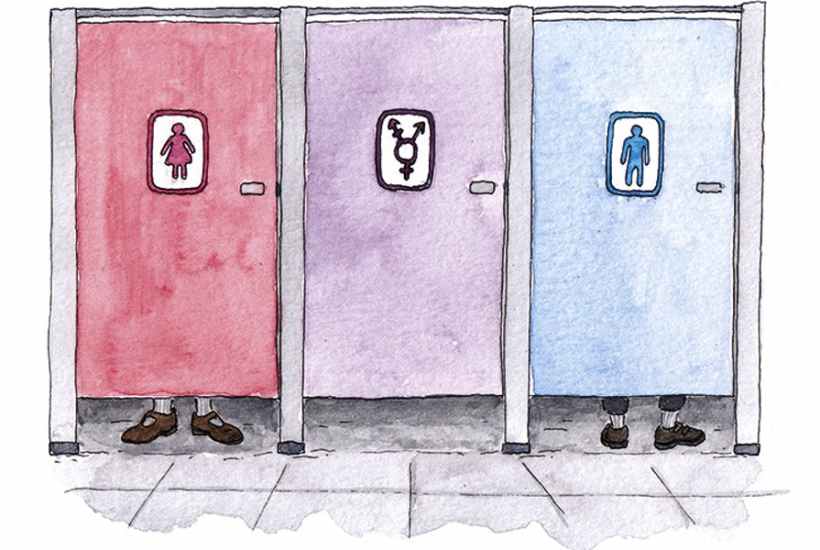

More broadly, feminists have rightly raised concerns that blending the two sexes could represent a green light for a man to access women’s prisons, refuges and sport competitions. There is also a risk that statistical data needed to understand the scale of male violence against women is muddled up.

As for women’s studies, this gender confusion also poses an important conundrum: if there is no material difference between men and women, why do feminists need an academic field devoted solely to one sex? This argument, along with the parasitic emergence of postmodernism, saw women’s studies shape shift into the more encompassing gender studies, and lately into a cooler incarnation in the form of queer studies. The revolutionary project was torpedoed from within.

Now as these departments churn out ‘gender specialists’ and ‘gender consultants’ into the world, intent on erasing biological differences from policy and legislation, we are all paying the price. Mediocre male athletes take gold in women’s sports competitions; women feel uneasy about whether their locker rooms and safe spaces are indeed safe.

Although I was never a true believer of ‘gender identity’ theories, I realised I needed to change my mind about some of the most strident arguments I had accepted as received wisdom. Will Labour do the same and ever come back from this brink? Under Keir Starmer’s leadership, it seems unlikely.

If so, they are making a grave mistake. While blurring the lines between the sexes has a certain appeal to both the academic and the political fringes, there are life and death conversations to be had about women’s health, safety and privacy. None of us need a dictionary to define half the planet’s population. We just need common sense and a backbone.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in