The outrage felt by many in the West in the face of increasing Russian aggression and the trails of blood and tears has led to some absurd, knee-jerk, excessive, and excessively impotent gestures of solidarity.

Much emotional energy has been wasted, for example, on irrational boycotts, such as recent calls to ban the Russian world number one tennis player Daniil Medvedev, or that of the famous New York establishment, the Russian Tea Room, which was actually opened by anti-communist dissidents escaping Stalinist Russia. In Australia, BWS and Dan Murphy’s have decided to dump Russian vodka, as has the supermarket chain Co-op in the UK.

While the above cases might be misplaced anger, symbolic gestures, or moral grandstanding that will have no effect on Putin or in any way help the Ukrainians, the most dangerous and nonsensical gestures are the attempts to cancel Russian art and artists.

For instance, the famous Russian soprano Anna Netrebko has been banned by the Metropolitan Opera in New York for not only 2022 but also 2023, with her being replaced for already scheduled performances. This is despite her making a clear statement opposing the war stating, ‘I am opposed to this senseless war of aggression, and I am calling on Russia to end this war right now, to save all of us.’

This was apparently not enough for the Met, which wanted from Netrebko a direct denunciation of Putin. This cynical and entirely unreasonable request goes to show how detached the Met is from the real world. While it costs them little in performing this moral peacocking, for a Russian citizen and a public figure, whose country is headed by a ruthless man who has a history of assassinating dissidents both within and outside of Russia, such a move may be fatal.

The Glasgow Film Festival decided to drop two Russian films by filmmakers Kirill Sokolov and Lado Kvataniya from its program. This is despite Sokolov having family in Kyiv and both having publicly denounced the war. The reason is ostensibly that both films, like most Russian films, had received funding from Russian government grants.

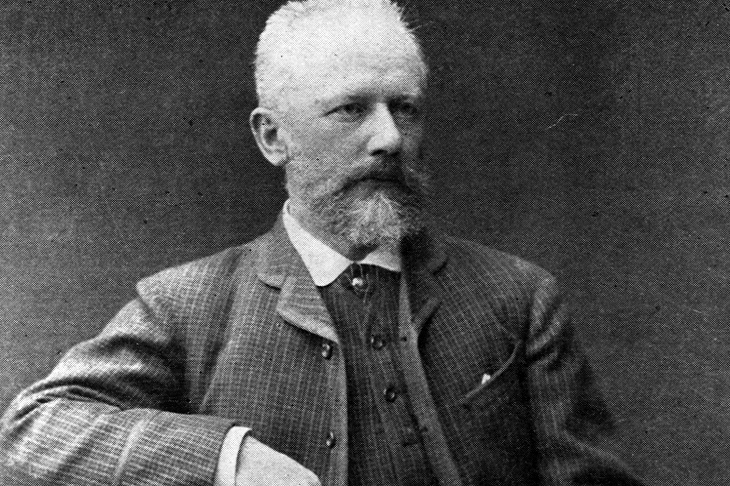

Perhaps most disturbing, the Cardiff Philharmonic Orchestra has removed the Russian composer Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture from its program. What Tchaikovsky, who died in 1893, has to do with the current war is certainly beyond me – but what all these attempts at indiscriminate Russian culturicide do give is an excuse for Kremlin propagandists, and indeed, everyday Russians to say ‘they hate us, not for what Putin is doing now in Ukraine, but us as a culture’.

Such moves may well chill the souls of the average Russian, the overwhelming number of whom are peaceable and good. With an estimated 11 million Russians having relatives in Ukraine, many have personal reasons to being anti-war. This is clearly shown by the sheer number of protesters that have braved the ruthless Putin regime in disgust at the war, despite state propaganda, and despite facing the real risk of violence. Indeed tens of thousands of Russians have already been arrested. These people need from the West, not derision and disrespect, but support and solidarity.

Too much emotional energy has been expended wantonly and in counterproductive ways, and the centre of things has been traduced in the process. And denying the exchange of art is a sure way to further taint and alienate a people who have little say in the machinations of their autocratic government.

With the backdrop of a 21st century war in Europe, art should be vivified to pierce the hides of the hypocrites, laugh at the naked emperors, and to console us in our sorrows and to amplify our joys.

Further to the effort of bringing Russian from under the shadow of dictatorial governance and towards liberty, art is a bridge that, in the words of F. Scott Fitzgerald, grants the discovery that your longings are universal longings. In other words, art is the path that can lead to the understanding of our shared humanity. And wars are made possible precisely by extinguishing such a realisation.

Killing art is the best way to sow the grounds for war.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in