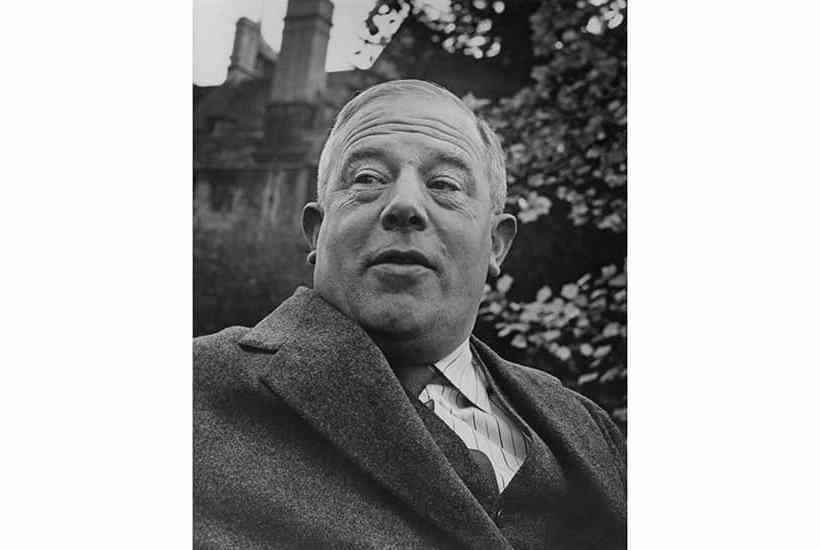

Evelyn Waugh’s Oxford friend Harold Acton, immortalised as Anthony Blanche in Brideshead Revisited, once bumped into the wife of John Beazley, a lecturer in ancient Greek pottery, while she was exercising their pet goose in Christ Church’s Tom Quad. Hopping over the bird, Acton intuitively doffed his hat. Here, Marie Beazley declared, was ‘a true gentleman’.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in