After years of post-Brexit rancour,the last few weeks have been a striking display of European (not just EU) unity. Britain was the first to send arms to Ukraine, now the EU is (for the first time) buying weapons so it can follow suit. No one forced Norway’s strategic wealth fund to disinvestall Russian assets, but it chose to. Even Switzerland is marching in lockstep with the sanctions. Putin had counted on European divisions, which had certainly been on display when Germany was still going ahead with the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, in defiance of protestsand pleas from Eastern Europe and the European parliament. The invasion turned this squabbling into unity: Britain may have left the European Union but when a European city is being shelled by the Kremlin what we see is a united Europe and a united West.

This is why it was not just misjudgedbut damaging for Boris Johnson to use his conference speech to compare the Ukrainian fight for national survival to those who voted for Brexit. We discuss this on today’s podcast. In his speech, the Prime Minister said:

I know that it’sthe instinct of the people of this country, like the people of Ukraine, to choose freedom, every time. I can give you a couple of famous recent examples. When the British people voted for Brexit in such large, large numbers, I don’t believe it was because theywere remotely hostile to foreigners. It’s because they wanted to be free to do things differently and for this country to be able to run itself.

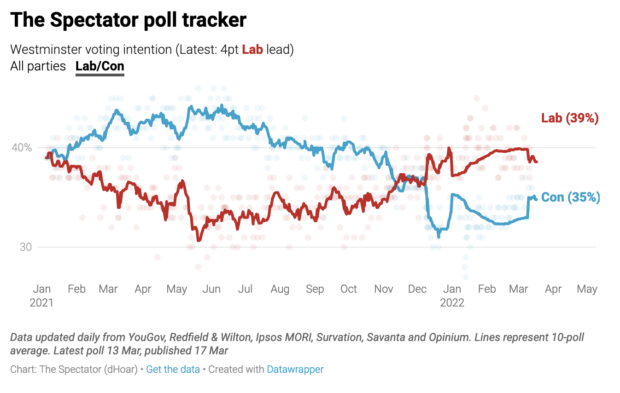

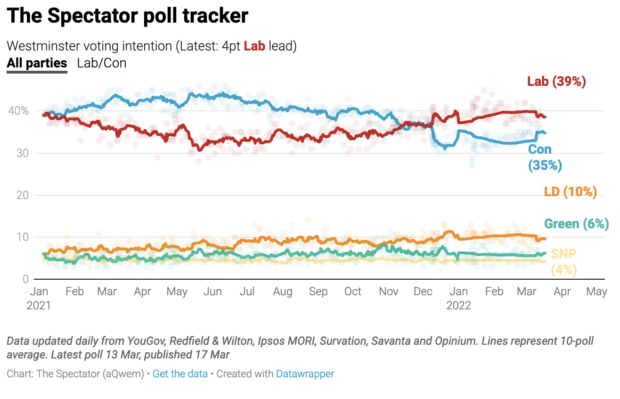

To do so was incendiary: he’d haveknown that. What does this imply about Remainers? That they were somehow less keen on freedom and (to extend his Ukrainian metaphor) white-flag raisers when freedom was threatened? Or might they have defined freedom as the ability to choose alliances? What Johnson may have hoped his speech had done was rally the Brexit faithful and reawaken partisan instincts at a time when he worries that the 52 per cent Brexit vote is far larger than the 35 per cent who support Tories (an11-point Tory lead has turned into a four point Labour lead – and he may well see leadership of the Brexit project as his main vote-winner).

But while a controversy might be helpfulin some ways, it is damaging in two other ways. The referendum did create a deep schism in the country and Johnson came to power as Tory leader saying he’d unite the country. It was the second letter in his ‘Dude’ leadership manifesto (Deliver Brexit, Unify the country, Defeat Labour, Energise the Country). But what if ‘unite’ (i.e. moving beyond Brexit schism) softens support for the Tories? It seems that Johnson isn’t as keen on that and now wonders whether, when it comes to Brexit, waris peace.

But he had another objective: to showEurope that Brexit did not mean Britain walking away from Europe but, instead, showed a better way of working with Europe, as an ally to the EU27 but independent from its structures. Ukraine was (and remains) a very powerful way of making that important pointto Europe and the world. A few days ago, No. 10 was lettingit be known that the PM was open to attending the coming European Council meeting.

But to insult the EU member statesmidway through – implying that they are somehow less keen on freedom because they stay inside Brussels – reawakens the old enmities. It redraws the divides that Johnson had been keen to rub out with his Global Britain agenda. It drew predictable condemnation from abroad – as well as from pro-Brexit commentators in Britain from Iain Martin to Julia-Hartley Brewer. (“Comparing the vote to leave the EU with the Ukrainian people fighting for their lives against a foreign invader,” she said, “is an insult to their bravery and sacrifice”.) The temptation to revive Brexit tribalism was stronger than his desire to reposition Brexit Britain as a the no1 ally of the bloc we left behind.

What did he stand to gain from throwingthat rhetorical Molotov cocktail in Blackpool? Revving up a Brexit tribe that has disbanded over the past few years and rallying them back around him. And what does he stand to lose? His position among ex-Tory voting Remainers and his reputation in European capitals, who had been starting to see him in a different light (and are now saying he should be a persona non grata in their coming summit). For a leader who wants to be seen as unifying rather than a divisive figure, I’m not sure it was worth thistrade.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in