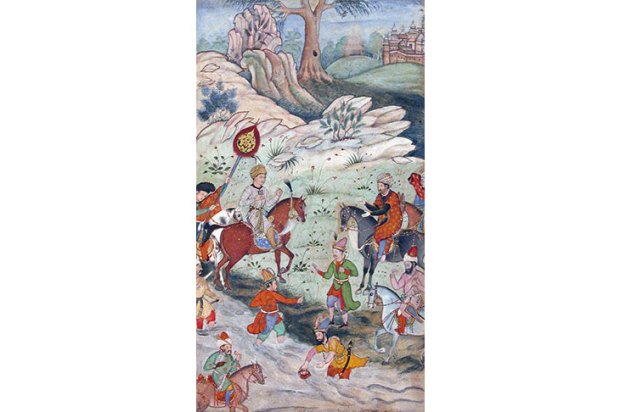

In this luminous, erudite book, Christopher de Bellaigue tells the story of the early years of Suleiman the Magnificent, the best known and most powerful of the Ottoman sultans.It is far from a standard narrative history. Drawing on sources in English, French, Italian and German, de Bellaigue has written a gripping account that evokes an epic poem, saga or ‘book of kings’ rather than a familiar biographical plod.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in