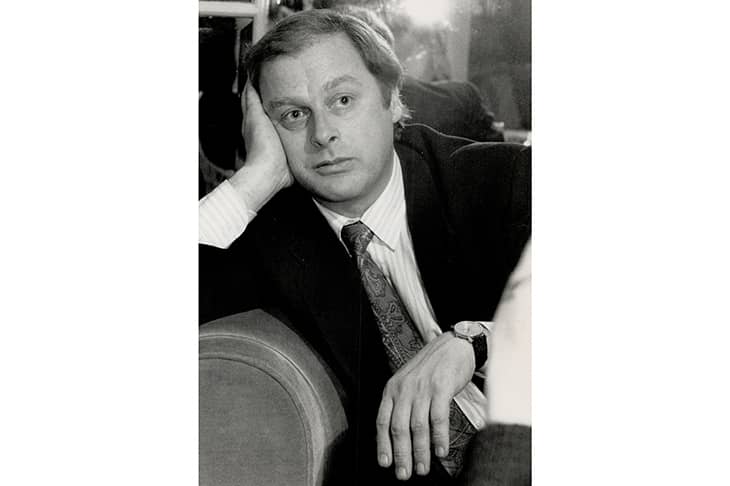

After a career spanning 50 years, 40 books and about a million parties, Anthony Holden has written a memoir. Based on a True Story is bookended by touching accounts of his childhood and old age. Born in 1947, Holden grew up in Southport. His adored grandfather, Ivan Sharpe, played football for England, winning gold at the 1912 Olympics.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in