Covid transformed the role of the state. During the pandemic, the government did things it would never normally even contemplate. At the same time as it restricted civil liberties, it intervened in the economy to an extent never before seen in peacetime. Through the furlough scheme, close to £70 billion was spent on paying people’s wages.

Other government economic interventions seem minor in comparison. What is a few hundred million here and there when the state has been spending billions so regularly?

History suggests that when the state expands in a crisis, it doesn’t revert to its pre-crisis level once the emergency is over. The second world war led to the industry nationalisations of the Attlee government, along with the creation of the National Health Service and the modern welfare state. After the first world war, the Lloyd George government extended unemployment insurance to most of the workforce, fixed wages for farm workers and introduced rent controls.

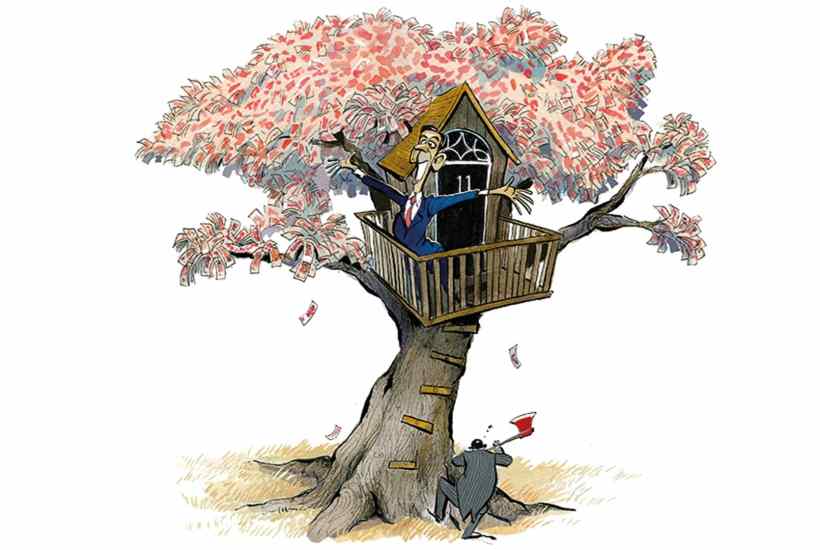

Last year, state spending exceeded 50 per cent of GDP for the first time since 1945-46. The question for the Conservatives is how quickly that share should be reduced, and how big, and active, government should be.

This philosophical question is what lies beneath the row in government over what to do about rising energy prices for businesses. The Business Department, supported by No. 10, wants state support for the industries hit hardest by the rise in the gas price. The logic is that the huge increase in costs is making otherwise viable businesses unsustainable, so the sensible thing for the state to do is to intervene, as it did during the pandemic. The Treasury, however, is nervous about the precedent.

There are significant differences between the energy price increase and the pandemic. Firstly, there is good reason to think that gas prices are going to remain high. As countries move away from coal, demand for gas increases. China is connecting 15 million homes a year to the gas grid, which creates a knock-on effect for supply worldwide. Europe’s own supplies have fallen by close to a third in the past decade. If the state steps in now, when it is hard to see how prices will return to their previous levels, it may find itself supporting these companies for the foreseeable future.

The UK is not the only country facing such challenges. The European Commission will, according to the Italian Prime Minister, Mario Draghi, bring forward a proposal to buy energy on behalf of all EU states at the next EU Council meeting. Leaked documents suggest that the most likely outcome is that the Commission will buy gas on behalf of any member state that asks for help. The thinking is that this would allow countries to build up strategic reserves that could be released when prices spike.

If the Commission were to do this, there would be pressure on the UK government to do the same. This idea is too much even for more interventionist ministers. One dismisses the idea of ‘the government trying to turn itself into a gas trader’. But stranger things have happened in the past 18 months.

There is another danger in all this intervention: can the country afford it? During the pandemic, the link between government spending and taxes was broken. Huge sums were spent without personal taxes going up. Instead, the government put most of the expenditure on the national debt. The Bank of England made borrowing not just possible but extremely easy. By nearly doubling its entire quantitative easing programme in the space of a year, the Bank ensured that there were enough buyers for all this new debt.

This was clearly a legitimate and reasonable response to a war-like situation. The question now is whether government can carry on doing this indefinitely without facing the consequences.

One of the reasons the Treasury was keen to ensure that the extra money going to the NHS and social care was funded, and not simply paid for by further borrowing, was to re-establish the link between public spending and taxation. The view among most Conservative MPs is that people have just about accepted the case for raising National Insurance contributions to tackle the NHS backlog. There’s a broader feeling within the party, however, that further tax rises will not be tolerated by its voters.

Even with total borrowing expected to be £50 billion under March forecasts, it’s thought the Chancellor has little room to manoeuvre as the country braces for inflation and a rate rise. The public-sector net debt is five times bigger now than it was during Margaret Thatcher’s first term, when her government was trying to tame inflation. A 1 per cent rise in interest rates and inflation would require the Treasury to find an additional £25 billion to service the debt — equivalent to the Department for Transport’s entire budget. The IFS estimates the Treasury already needs to find an additional £15 billion, which is more than the Home Office budget, just to pay the debt interest this year.

The Bank of England predicts that inflation will reach 4 per cent by the end of the year. Some think this underestimates the problem. One Secretary of State told me that they expect inflation to be at 6 per cent by the end of the year, three times the Bank of England’s target. Markets think similarly. Little wonder that there’s a growing expectation in Whitehall that there will be an interest rate rise before the end of the year.

The UK is on course for its highest ever sustained level of taxation. The country’s ageing population will lead to demand for increases in spending on health and social care. The state will grow only larger unless there is a concerted effort to both control spending and boost the growth rate of the economy. Without that, the UK will drift towards an era of higher taxes and lower growth. The longer the Covid mindset lingers, the harder it will be to stop that drift.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in