Conservatism is a philosophy of change. Not that this is well recognised by its chorus of hyperventilating critics, nor particularly well understood and articulated by its increasingly rowdy proponents.

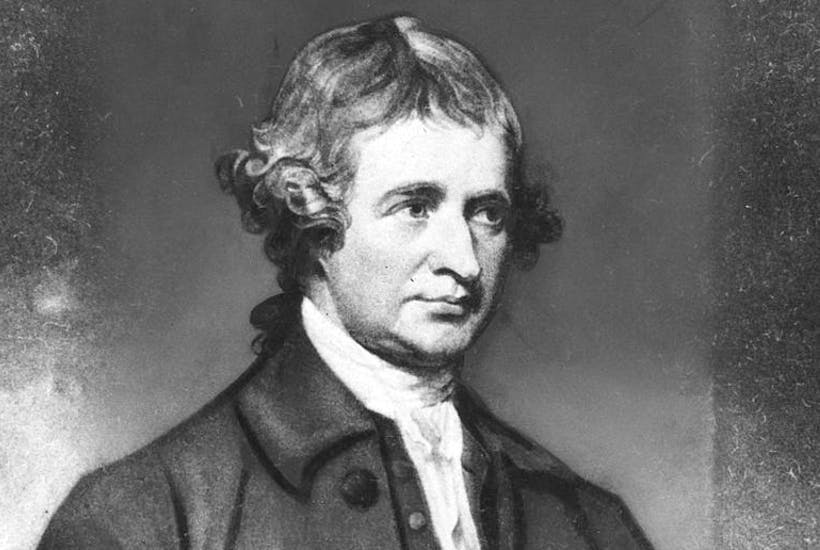

It was no less than Edmund Burke, that great unwitting progenitor of conservatism, who observed in his celebrated critique of the French Revolution that “a state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation.” The idea that social change is both necessary and positive has been essential to the meaning of conservatism since its inception.

Russell Kirk, the great American populariser of Burkean conservatism, noted that the “better men among [Burke’s] disciples” understood that “change in society is natural, inevitable and beneficial.”

The distinguishing mark of conservatism, according to Kirk, is the insight that a prospering and stable social order can only be established and sustained by successfully reconciling innovation and prescriptive truth, or the permanent things, as he so often put it (borrowing from friend and fellow conservative T.S. Elliot). Burke, and intellectual heirs like Kirk, understood that the lesson of the French Revolution was not that change is bad per se, and thus something to be resisted reflexively, but that failing to make prudent and necessary changes to preserve the continuity of an existing order risks catalysing destructive radical change.

Conservatism is far from the only political philosophy in possession of an attitude to change. Change is, after all, at the heart of politics—an arena in which rival proposals for change, sometimes euphemistically called “visions,” vie for adherents amidst opposition in the hope of implementation.

If anything, conservatism’s philosophical rivals have made a virtue out of an obsession with change. Liberalism aims to provide the maximum freedom possible for people to pursue their own individual interests and desires, which is to say the incubation of endless innovation, atomisation and diversification, albeit within a system of institutional constraints.

Libertarians want to turbocharge liberalism’s innovation and individualistic self-determination by removing most of those constraints. Anarchism wants to do away with constraints altogether in the fantastical belief that spontaneous combustion is capable of producing a stable and just social order.

Progressivism regards the existing order as racist, sexist, homophobic and transphobic, which is to say systemically unjust and oppressive, and thus in need of radical structural surgery in order to root out injustice, which apparently is to be found in social structures, not human hearts.

Marxism aspires to the creation of a new classless nirvana by revolutionising virtually every aspect of social life, from the means of production to human nature itself.

Even fascism, though animated by romantic notions of national identity, solidarity and destiny, is in actual fact driven by change, or more precisely the fear of change—domestic traitors and external enemies who threaten to bring down the sacred order.

Conservatism possesses the most coherent and pragmatic philosophy of change. The conservative accepts that society must always remain open to the possibility of change. The ineradicable presence of injustice, fallible human minds, corrupt human desires and maladministration demand it. But the conservative also knows that change is most effective and beneficial when done prudently within a framework of tradition and custom in continuity with the past.

The fact is that existence is dynamic, not static, whether we are talking about an economy, a nation-state, the geopolitical order, the climate, language, culture, the life-cycle of the human being or the expansion of the universe.

However, this existential dynamism is regulated, not absolute—the latter would amount to chaos. The perpetual evolution characteristic of all existence occurs within a system of regulating constraints, whether those that occur naturally, such as the laws of physics, or those created and imposed by human cultures, such as legal systems. Political philosophies succeed or fail to the extent that they can successfully manage, balance and integrate continuity and change.

This is not always straightforward and easy in a complex and dynamic world, as the policy challenges of climate change and the covid pandemic demonstrate. Neither a de-carbonised economy nor social distancing form part of the norms and customs of Australian social existence. In that regard, both represent novel circumstances which necessitate some degree of innovative response.

The primary response to covid has been lockdowns, which constitute extreme disruption to multiple traditions, including those of socialising, commerce, work, entertainment, education, travel, and more. The most compelling argument in favour of lockdowns is to buy time to build hospital capacity, especially ICU capacity, given it is evident that the unsuppressed spread of the disease can place a significant burden on health resources. But the case for lockdowns and other covid-related restrictions are only compelling insofar as they are temporary and proportionate, given the manifest and widespread harms they generate.

As such, the conservative can in good conscience support the minimal restrictions required for the very specific goal of enhancing hospital capacity and only for the absolute minimum time required, but must stand against any attempt to pervert existing institutional norms and customs beyond covid, or to impose new norms that are simply unnecessary or harmful. This includes a principled stand against vaccine mandates for both employees and patrons, except in very limited contexts (a reasonable case can be made for aged care facilities and ICUs given our knowledge of how deadly the disease can be in those settings).

Australia has no tradition of denying employment and service to the unvaccinated. We have no tradition of two-tiered citizenship. In fact, long before covid we managed to live a fruitful existence in the presence of citizens who chose not to receive one or more vaccines for any number of reasons. Moreover, given the vaccination coverage in Australia looks set to be very high, and given the fact that it is still possible to be infected with covid and spread it while double-dosed (albeit at lower rates than the unvaccinated), there is simply no need to adversely interfere with the traditional freedoms that have long defined Australia.

The conservative is not blind to the need to adapt and respond to unprecedented emergency circumstances, such as those of a pandemic. But nor is the conservative willing to let a passing emergency radically and permanently reshape the traditional norms and customs of society.

To say that the issue of climate change has seen the conservative side of Australian politics tie itself in knots would be a gross understatement. For some it is scepticism about the science, for others it is scepticism about the capacity of green technology, for yet others it is the impact on jobs in threatened industries, like coal, concentrated in regional areas that has led to caution or outright resistance to the idea of Australia making a transition to a carbon-neutral economy.

But the truth conservatives need to confront, at least those still sceptical about the science, the costs or the capacity to make the transition, is that the climate ship has already sailed. The only choice now is to steer the ship or wave at it from the shore.

The rapidly evolving global investment and regulatory climate, in conjunction with massive and growing research and investment in green technology, make a transition to a carbon-neutral economy (or something approximating it) a question of when and how, not if. The idea that Australia can hold out and prosper in this new global paradigm, and that jobs in coal and other carbon-heavy industries can be preserved in perpetuity, is no longer credible. The global (and domestic) investment and regulatory environment will inexorably move in one, and only one, direction from here.

Acceptance of this reality leaves only one prudent option for conservatives: seize the reigns of transition to ensure that it is done sensibly, effectively and with the minimal harm possible. The alternative is not non-transition; It is a Labor government, egged on by the Greens, that pursues an aggressive, accelerated and radical transition pregnant with risk.

Discerning both the necessity and efficacy of change is an act of wisdom. It requires a heavy dose of empirical realism, a strong sense of justice, a set of true, yet practicable principles and careful consideration of effects. In short, it is an art, not a science.

Sadly, not all social problems can be resolved effectively and justly, not all proposed changes address real and urgent problems, and necessary changes implemented poorly can wind up doing more harm than good. Some changes, as climate change and covid demonstrate, are undesirable, but necessary and unavoidable.

In a world dominated by inflexible ideologues obsessed with change, from covid fanatics to climate catastrophists, conservatives increasingly find themselves tempted by the false allure of revolutionary fervour (think January 6), postliberal (read authoritarian) promised lands, quixotic theocratic fantasies and fetishistic daydreaming of bygone ages.

Such temptations not only represent an abandonment of the legacy of Burkean conservatism, they promise to relegate conservatism to the margins of society, leaving the door wide open to those with an insatiable appetite for change.

If conservatism is to have any influence over the course of our inexorable social evolution, it must urgently rediscover its essence as a philosophy of change in order to “lead,” as Kirk put it, “the waters of novelty into the canals of custom.”

Jonathan Cole is an academic and host of The Political Animals Podcast: “Honest conversations about the political, theological and cultural ideas that shape who we are in the 21st century”. He tweets at @polanimalspod.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in