Should Stanley fall? Debate is raging over whether a statue of the Victorian explorer Henry Morton Stanley, which was erected in his home town of Denbigh in Wales a few years ago, should be pulled down because of his racist views.

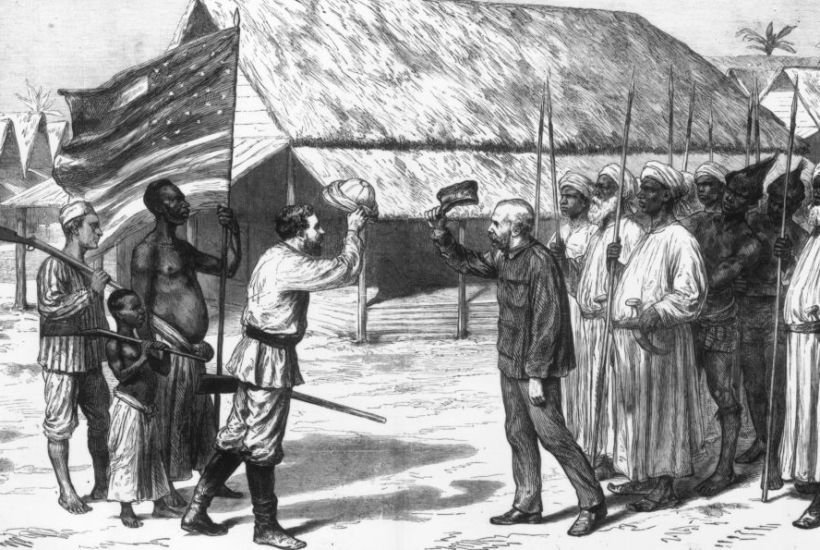

Stanley is, of course, best known for the four words he uttered when he found Dr Livingstone destitute in the middle of Africa. But his lesser-known activities during his travels have now led to a public consultation being set up in the wake of last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests. That consultation is tasked with deciding the fate of his statue. So should the monument follow the lead of Edward Colston and be taken down?

Stanley’s defenders point to the explorer’s writings, in which he passionately rallied against the evils of slavery, to suggest that Denbigh’s most famous son has been unfairly maligned and his statue should stay. Missing from the debate though is Stanley’s dark record when it comes to slavery, and how he actually behaved in Africa.

When he set out to find Dr Livingstone, Stanley bought three boys, Kalulu, Bill Ali and Majwara, from slave traders to act as his gun bearers, paying $20 for each child. In his diaries, Stanley freely admitted that he would have bought more were it not for the cost. Slavery had long been abolished by Britain by that point, but he was in the territory of the Sultan of Zanzibar and was passing himself off as an American.

Many explorers in East Africa used slave labour for their expeditions to the centre of the continent, but often they hired them so they could claim to not be directly involved in slave trafficking, or suggested they were only dealing with free men. In the last expedition he made across Africa, 15 years after he found Livingstone, Stanley even dropped this pretence that his porters were free. In February 1887, before his trip, he entered into an agreement with Tippu Tib (the world’s most notorious slave trader) to hire 600 men, knowing full well that Tippu Tib would need to capture and enslave local Africans to meet the order.

On his return to the coast, Stanley was forced to recruit more local men and women to act as porters and did so through coercion. As one of his companions explained:

‘Stanley sent Stairs to make a raid on the natives who had not come in to make friends with us and seize cattle, he went out and brought in 125 in a very few hours.’

Stanley then put the word out that locals would get their cattle back if they agreed to help the expedition.

It gets worse still. As Jephson explained in his diary entry of 20 April 1890:

‘This morning Stanley told us to count over the slaves, chiefly women and children, whom our people had caught and hand half of them over to the Pasha to give to his people. This Stairs and I did and handed him over 20. We brought them over to the Pasha’s house, upon my word it was a most shameful scene and was every bit as bad as the open slave markets which existed in the East till virtuous England set her back up. Orders are however orders and we must obey them in spite of the heartrending scenes and shameless brutality we see in these raids.’

The truth is that whatever Stanley wrote about the evils of slavery, he travelled with, negotiated with, befriended, supported and encouraged the men who controlled the trade. In the process, he became directly involved in the wholesale killing, kidnapping, ransoming, sale and maiming of people he claimed to be helping.

He also had a terrible record for violence against indigenous people, but has often been excused on the basis that he was bravely defending himself from attacks on his expedition. Is this right? Stairs describes one incident where Stanley attacked a group of natives, unprovoked:

‘While we were clearing a place for camp a Washenzi canoe sailed quietly by without seeing anything of us. All kept silent for a few seconds, till Stanley and I opened fire with our Winchesters. We each killed one and wounded two others.’

In truth, Stanley deliberately adopted shock and awe tactics on the continent to overwhelm the local people. In one instance, Jephson writes

‘Stanley stepped out and taking a good steady aim with his Winchester Express fired at a native 550 yards distant and shot him through the head. The natives all rushed up to the body and were so utterly thunderstruck at the possibility of our being able to kill a man at such a distance that they took to their heels as hard as they could pelt and a body of our men pursued them until they were out of sight. Stanley had the dead native cut up, the Zanzibaris mutilated the body in a horrible way. He said it was the only way to put fear into the natives so that they would cease to attack us…’

As the debate rages on about whether the statue of Stanley should be pulled down, it seems incredibly foolish to focus solely on his racism when his actions in Africa were so terrible. Have we really reached the point when the worst thing we can say of Stanley was not that he was a murderer and slave trafficker, but that he was a racist?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in