They say the city you most fondly remember is the one you grew up in. In my case that’s Kabul. I spent my formative years in the Afghan capital in the mid-1960s. It was a very different time and Afghanistan a very different country. But the Kabul that’s imprinted on my mind belongs to that decade.

It was a happy city. No other description does it justice. Of course, it was poor, conservative and hierarchical but people were always smiling. They were warm, welcoming, courteous and generous. This was most obvious in their attitude to children. Everyone called me ‘bacho’. When Mummy took me out, shopkeepers would slip Hershey’s chocolates or spearmint gum into my hands and then seal my lips with their fingers. It was our little secret and it made a nine-year-old feel special.

Every morning Khan Mohammad would hold my hand and walk me from the ambassador’s residence, past the Italian embassy, to the corner of Ariana Hotel to await the school bus. Across the road was Dilkusha Palace. A little further was Pashtunistan Square and the Khyber restaurant, famous for its beef steaks and lemon meringue pies.

Daddy’s office, as I called it, was in Sharinau, not far from what later became famous as Chicken Street. In the Sixties it was literally a place to buy fowl. Carpets and antiques were nowhere to be seen. The birds were crammed into wire-mesh coops. Mummy would pick her choice and the chicken would be slaughtered in the ‘jui’ or drain that ran alongside. She would look the other way, I was transfixed by the gruesome slaughter.

Old Kabul lay beyond Pashtunistan Square. It was a warren of shops surrounding the Pul-e-Chisti Mosque, an amalgam of money-lenders, jewellers, second-hand clothes stores, naan bakeries and dingy little supermarkets. In fact, there was nothing ‘super’ about them but the American term had caught the Afghan fancy.

The grandest hotel was the eponymous Kabul. The Inter-Continental was still a few years into the future, The Serena decades away. But there was a delightful Swiss hostelry called Spinzar. Its pastries were delectable. Overlooking the Kabul river, it stood at the end of a long row of little shops selling Afghanistan’s prized Karakul caps.

On Fridays we would drive to Kargah Lake, just beyond the city limits, or even further to Paghman, where the royal family and aristocracy had summer homes. The restaurant at Kargah was rather posh. But I preferred the handcarts selling candyfloss and Coca-Cola in old fashioned bottles.

Society, in the Victorian sense, was small but sophisticated. The upper classes spoke better French than English, but they all warmed to Indian classical music. Vilayat Khan and Amjad Ali were favourites. Hindi films were adored and Dilip Kumar was every Afghan’s hero.

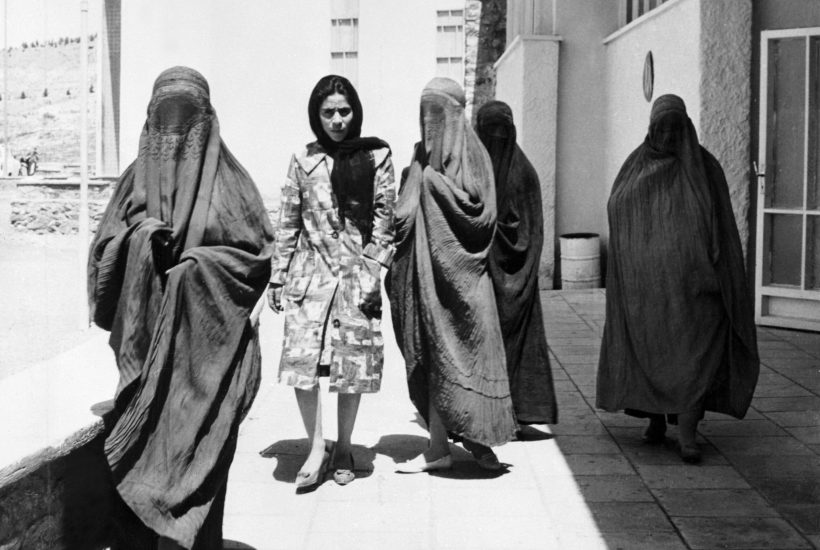

The rich lived behind high-walled compounds. Outside some women wore burkas. Indoors, however, it was Chanel dresses and high-heeled shoes. They smoked American cigarettes held by carefully manicured fingers with bright red nail polish.

Those were innocent days. Grass grew in gardens and dates were numbers on a calendar. Even parents were incredulously trusting. When Daddy fell ill he was surprised at how often the princes would drop by, until it dawned on him that the real attraction was his daughters.

Much of today’s Kabul didn’t exist. Wazir Akbar Khan was a vast barren spread. From our upstairs balcony there was an unbroken view all the way to the Pakistani residence. The American ambassador lived opposite the Indian chancery. The present-day US compound was scrubland. It was here, when he was free and feeling indulgent, that Daddy taught me to drive.

I studied at the American School at Karte Chaur. A little further was Dar-ul-Aman Palace, built by Amanullah in the early 1900s. If we didn’t go to Kargah we would spend Friday afternoons swimming in the palace pool.

When Mummy found I’d acquired an American twang and started saying ‘aloominum’ she packed me off to school in Dehradun. She was determined to protect her son’s accent. But that didn’t cure my taste for peanut butter. I have it every day at breakfast and each bite brings Kabul back to mind. Unlike Robert Graves, I cannot say ‘Good-bye to all that’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in