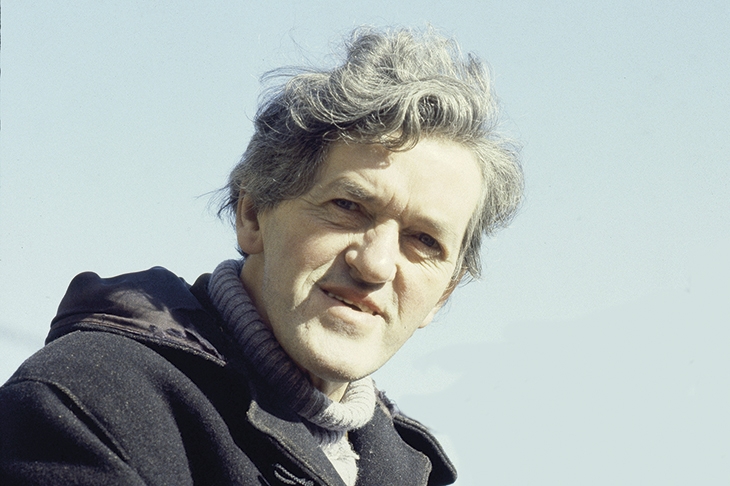

Few journalists can have conducted such a dismal interview as mine with George Mackay Brown in the summer of 1992. The Times had sent me to Orkney, and the night before we met I sat up in my B&B reading his poetry, spellbound. So much to ask him! But that first meeting was a disaster.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

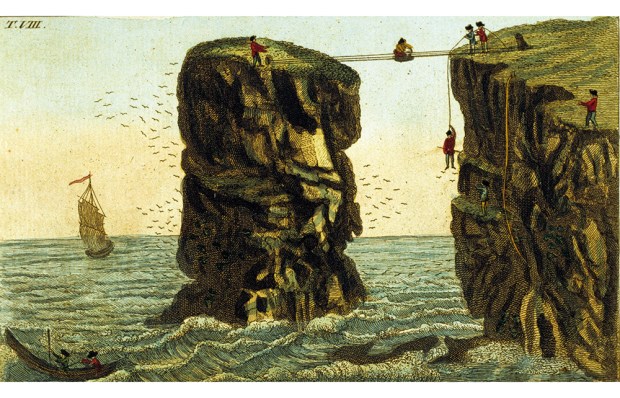

Carve the Runes: Selected Poems, edited by Kathleen Jamie; Simple Fire: Selected Short Stories, edited by Malacky Talack; An Orkney Tapestry, edited by Linden Bicket and Kirsteen McCue (Polygon, £12.99 each).

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in