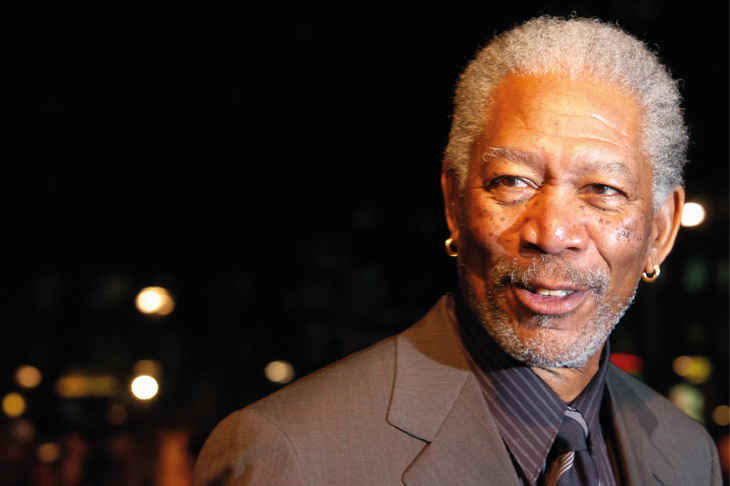

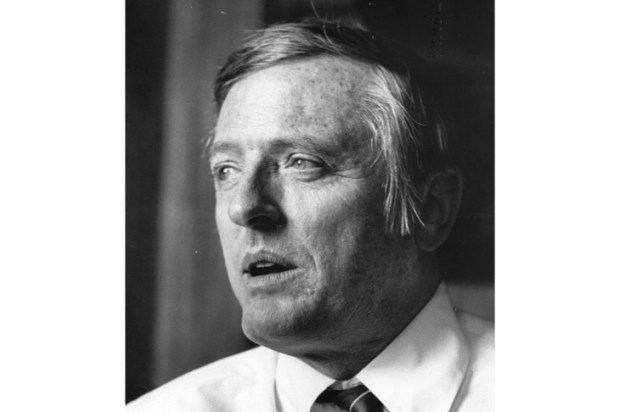

It’s an extraordinary thing that a director of Bruce Beresford’s reputation should be directing for Melbourne Opera until you remember that opera is one of the performing arts the famous film director lives for and that he has never been interested in position, only in what fires his imagination. The man who effectively discovered Morgan Freeman, who is entirely grateful to Tommy Lee Jones for making the ‘shithouse dialogue’ of Double Jeopardy ‘sound like Flaubert’ and who knocked unannounced on the door of the Irish novelist Brian Moore to persuade him to let him film Black Robe – his best film, he thinks, because he wanted to bring to the screen that capacity to step back to 1629 when the Algonquin encountered the Jesuits – is in love with opera.

Shakespeare’s Scottish tragedy written for that witch-watcher James I is a generation earlier than Black Robe though it belongs to the formative modern period by which we define ourselves and Verdi’s Macbetto comes from his earlier period though he was already an artist, in Shaw’s phrase, whose every bar of music furthered the drama. Beresford has created a production of the operatic Macbeth which has a constant intensity and a magnificent performance from Helena Dix as Lady Macbeth and a tough, probing stab at Macbeth from the baritone Simon Meadows whose every pulse is devoted to the delineation of the excruciated thane who takes evil as his good in his fated groping for the crown.

This is a potent and satisfying Macbeth even though the Verdi of 1847, revised for the Paris Opera eighteen years later (1865), does not have the towering majesty of, say, Don Carlos or indeed Otello in matching the power of Shakespeare’s dramatic articulation, its unreachable fierceness and grandeur.

None of which is to deny that this is a better Macbeth whether in music or in verse, than you’re liable to see on any crow-haunted winter’s night. Verdi’s Macbeth is one of the great Callas roles and it begins in speech with this fortress of a wife reading Macbeth’s letter about ‘the day of success’. Dix has a musical range, from high soprano to deep, deep contralto but she can also startle with a capacity to render the unknowable. And the fact that all the glamour is in the voice box not the singer’s physical form somehow works to highlight the way in which a woman shaped by marital devotion and the pieties of partnership comes to surrender to an idée fixe that will destroy all.

But she can conjure thought, she can manifest obsession and a fear that can only be conquered by being surrendered to. Simon Meadows is a credible noble warrior gone bad. The voice quivers with doubt then desperation as it clings to convey the searing poignancy of a world that has ceased to signify anything. That last aria – the prospect of troops of friends lost forever – is very fine.

Much of the stage is dark. The costumes by Greg Carroll are rich and medieval. Adrian Tamburini is a fine capable Banquo and Samuel Sakker is a magnificent Macduff. Verdi’s witches are like an ensemble of young Milanese fashionista wannabes and their flightiness is a winning variation on Shakespeare’s old crones because it highlights the claustrophobia of the central drama of marriage and murder. Greg Hocking conducts with consistent sprightliness and verve and feeling for the shifts of the drama.

But this is a fine flawlessly consistent Macbeth, full of darkness with flashes of blinding revelation and Beresford ensues that in the face of the impossible it retains dramatic weight and human credibility.

Macbeth is often thought of as a curse of a dramatic venture and legend has it that the American baritone Leonard Warren actually died singing Verdi’s version. Peter O’Toole had the great disaster of his stage career as Shakespeare’s thane and the Australian actor Keith Michell said that Olivier, the most highly regarded Macbeth of the twentieth century, almost blinded him when he was laying on against his Macduff. Callas’ recording has a sibylline subtlety and Sean Connery said playing Shakespeare’s silken villain taught him how to play James Bond.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in