In the days after the Duke of Edinburgh’s death, there was much eagerness to hear from a particular group of royal watchers: the folk of a few tiny villages in the South Pacific where the late Prince was venerated as a mountain god.

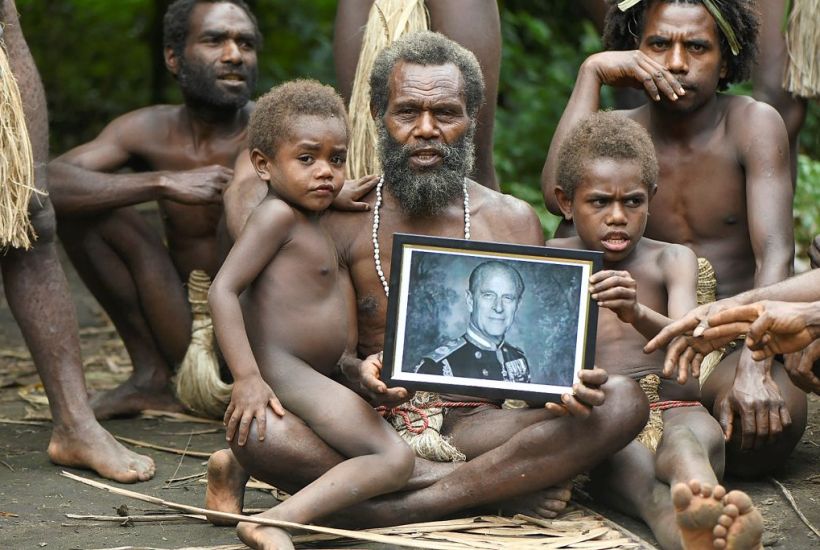

When a video message did eventually surface, rolled out among the broadcasters, the world saw a gathering of bearded faces sending solemn condolences. The depth of sentiment probably surprised a few viewers. After all, the ‘Prince Philip cult’ is often framed rather frivolously in our media. But the feelings among these people for the Duke are genuine.

I’ve spent time in Vanuatu with the Yakel tribe who believe Philip’s return was prophesied. Life there, in a village dappled with light beneath a banyan tree, remains traditional. For visitors, the elders will reverently unwrap a woven-leaf bundle of photographs of the Prince, including one that shows him holding a club, used locally for sacrificing pigs. (The photo was sent by Buckingham Palace, in the 1970s.)

But amidst the recent flurry of attention, an important thread was overlooked. For believers, Philip is an avatar of something older than royalty, and not just Mount Tukosmera nearby. It’s a rebellious spirit, anti-establishment. To understand Philip’s totemic power in Vanuatu, one has to plumb its origins.

At the start of the twentieth century, Vanuatu – or the New Hebrides as it was then inaccurately known – was jointly ruled by the French and British. With them came a legion of missionaries who taught at village schools, mandated the wearing of clothes and prohibited kava – an intoxicating juice made from a local root.

During a particularly austere period in the 1930s, a rumour went around Tanna island that a great change was coming. A man in a coat with shining buttons had appeared to some locals on a beach saying that, when he eventually returned, the old would become young, mountains would part, and the cargo arriving into the New Hebrides on white men’s boats would be given back to them, its rightful owners. Crucially, his arrival would reinstate their traditional way of life before centuries of imperial interference – especially kava drinking.

It may sound occult. But it was a portent of anti-colonial zeal, with a readymade figurehead; the mysterious messiah on the beach called John Frum.

During the Second World War, US military occupied the New Hebrides. The harbours were flooded with exotic goods and bottles of Coca-Cola. Some islanders, struck by the extravagance and the sight of black and white soldiers marching together, wondered if John Frum might be an American G.I. (Some still do – one faction raises a star-spangled banner, and annually re-enacts the old army drills with bamboo muskets.)

According to the Yakel, Frum got on an American steamer after the war and went to Europe: ‘The source of what threatens our culture,’ they say. There he dazzled the Queen, and his subsequent dukedom was a stopgap before he’d triumphantly return to Vanuatu.

How the Duke got entwined with the John Frum story is anyone’s guess. It’s thought his 1974 visit to the New Hebrides, when Philip reportedly sipped a ceremonial shell of kava, may have got locals talking.

Contrary to speculation over the last fortnight, I don’t think their movement failed because the Prince never returned. In fact, those journalists scrambling to get a quote from the tribe are just another facet of the prophecy fulfilled.

The sheer volume of people who come to Vanuatu to meet Philip-believers – international media, filmmakers, authors – is extraordinary. In 2006, a film company offered to fly some of them to the UK for a Channel Four series, Meet The Natives. The tribespeople reflected on the British class system and even got a private audience with the Prince. (A rather more crass take, Meet The Natives USA, followed.)

On our first visit to Yakel, an Australian was shooting a feature film with the villagers as the cast; Tanna ended up nominated for an Oscar.

Then there are dreamers, like Frank, a Norwegian seeking some kind of Eden, who moved out to Yakel and burned his clothes and passport. The tribe didn’t particularly mind him being there. Jimmy Joseph Nakou, their spokesperson, puts it like this:

‘When the spirits of our ancestors, or the spirits of our food crops, come to this world to live with us, they will come in the form of white people.’

He’s right. The lure of the Prince Philip story keeps us coming. We pay the Yakel for the privilege of investigating it, rightly so. Say what you will about the tribe’s beliefs but the prophesied ‘cargo’ has over the years arrived, in one form or another, and their way of life remains defiantly their own. To this day, 4pm is very much kava time.

What happens next is unclear. Perhaps Charles may unknowingly take up the mantle. What will endure, however, is the spirit of the movement: a rejection of dogmatism, of anyone telling you what to do, and a deep veneration for one’s own traditions. Philip, I suspect, would approve.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in