I’m a card carrying, Europe-loving, wishy-washy centre-left liberal. It therefore pains me to point this out: the EU in general, Ursula von der Leyen specifically, and some of the prominent European leaders such as Emmanuel Macron are getting policy and messaging on vaccines badly wrong. They need to urgently ditch the peacock displays of tribal politics. The French president, in particular, who leads one of the most vaccine sceptical western nations, should not have so publicly questioned the efficacy of what has clearly turned out to be a vaccine that is working in the fight against Covid-19. The consequences of their words could well be long-lasting.

‘The early results we have are not encouraging,’ said Macron earlier this month, referring to the vaccine effects for 60 to 65-year-olds. His words were premature at the time and look even more so now, in the wake of fantastic data showing the effects of the ChAdOx and Pfizer vaccines in the real world, with around a 94 per cent and 85 per cent reduction in hospitalisations.

I am an investigator in the ChAdOx vaccine studies, so I have a stake in these trials, but nonetheless the facts speak for themselves: the Oxford vaccine is helping to ensure that many people do not fall seriously ill from coronavirus.

It’s true that there are important caveats in the data published yesterday. The timings of when the vaccines were given are slightly different and affected by the extended second wave and subsequent lockdown, so it is not wise to compare the two vaccines head-to-head. This is known in the business as a confounding variable in an observational study and it is why randomisation is the keystone of modern trials. It means you need to take any conclusions with a pinch of salt. Despite this, the main take home message is that once the vaccines are given time to work, they work spectacularly well.

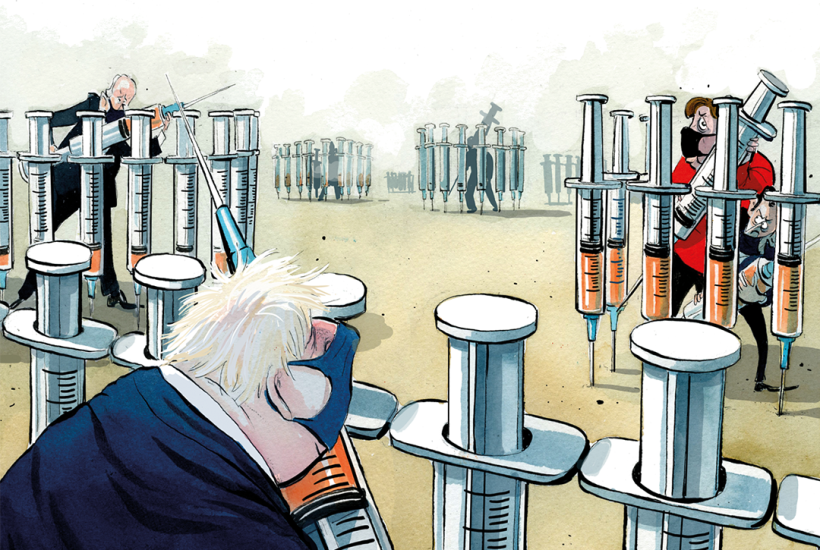

Yet across the Channel, there are reports in France, Germany and other countries of ChAdOx vaccines being left unused and even healthcare professionals expressing reluctance. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the misinformation put out by the likes of Macron has had some impact here.

The snail-like roll out of the vaccines in Europe has, of course, been well covered. But the mud thrown at the Oxford vaccine has decidedly stuck. Our government has been pleasantly restrained in not taking the bait and demonising the EU in return.

There are signs that the unfair criticism levelled at the Oxford vaccine may also be affecting decisions outside Europe. South Africa, where at least there might be mitigating circumstances with the ubiquity of the B.1.351 variant which has shown some evidence of diminished effects to most of the vaccines, has reportedly asked the Serum Institute to take back 100 million doses of the Oxford vaccine. In Australia, some scientists have suggested the Oxford vaccination should be paused.

It has been a source of enormous frustration to watch an effective vaccine that is convenient enough to be used in diverse settings and which has explicitly achieved a goal to be affordable for the whole world to be criticised by those who should know better.

So how did we get to this sorry state of affairs?

The first thing is to understand the criticism, some of which is fair. The critical Oxford vaccine trials were not run by AstraZeneca, but were funded through a mix of charitable and UK grant funding. Rather than one massive international pharma sponsored and run mega-trial, there were several smaller but linked studies.

Put simply there was less money in these trials. They did, however, have the formidable engine of the UK National Institute of Health Research infrastructure to aid them. They were run at a breakneck speed. I have written extensively about how this process had no impact on safety and these early articles are ageing well as the real world experience confirms this view.

However, the sped up timeframes used initially meant less time was available to be clear what a perfect trial would look like from the perspective of showing that a vaccine works. This is quite a technical and poorly understood point but it is important.

All of the trials took slightly different approaches in what they defined as a ‘positive case’, how big they were and how fast they might accumulate the all-important ‘events’ (those positive cases). They took different approaches to boosters and whether to do screening for asymptomatic cases. This field has now settled, partly because most companies will do what the FDA want them to do, but the Oxford vaccine was not aimed primarily at the FDA and for a variety of reasons it looked different.

Next we come to the much publicised initial problems surrounding the batch manufacture ‘error’ and dramatic headlines across the world when individual possible adverse effects were being reported. Because the Oxford vaccine was effectively the first to be rolled out in large populations, these events were reported in real time, inaccurately and with a megaphone. Science should not work like this but it is understandable. Further down the line, neither of these things appears to be of any major importance but mud sticks.

Next up on the slate is the decision to publish a ‘meta-analyses’ of results from the differing trials early. This was taken by an independent committee who had reviewed the results of the trials. They felt the ethical thing to do was to publish early, largely because this data passed the bar that international regulators set out for a successful vaccine. While this decision was commendable, it meant the early data was more complex to interpret. Inevitably, some conflicting international reporting followed and political agendas could be seen creeping in. That some countries have still not licensed the Oxford vaccine on the basis of this data should be a matter for reflection on their part, but each country has its own local tensions.

Lastly is the older population issue. The bulk of ChAdOx participants in the biggest trial were healthcare workers (HCWs) and by definition not going to be over 65. This was partly pragmatic, as unfortunately HCWs were the most high-risk and therefore most likely to generate positive cases.

If you think back to last May there was still uncertainty over what the second waves might look like, so this was a decent bet. Starting in a younger, healthier population is also always the safest way to do something as you are less at risk of unrelated but significant co-existing problems being potentially associated with your therapy. The additional trials in older subjects are still ongoing but I personally feel all of this was poorly explained generally and mendaciously misrepresented in some places.

Now we come to the bigger problems. All of the above would normally be minor, interesting technical issues for nerds like myself to mull over in conferences. They have unfortunately fallen victim to international good- and bad-faith scrutiny and the worst impulses of nationalism (and in the case of the EU bloc-ism). There has been some very poor quality reporting and unwise interventions from scientists who should, but often don’t, know better.

In the UK we have done a good job of maintaining vaccine confidence. This is partly historical, partly accident and partly, I like to delude myself, due to enthusiastic amateurs like myself trying their best to counter vaccine myths.

However this is also undoubtedly because we had skin in the game. The historical part is that we are usually quite a vaccine confident nation. On top of this, there was definitely some jingoism that one of the front-runners was home-grown and so reporting in the UK was generally more lenient and restrained.

The government was positive but muted. There was no central-led strong public information campaign. This was in some ways a positive thing because government voices are not necessarily the most trusted in this area. The regulators were brilliant and kept it simple. Trials were obviously safe and effective. The trees did not obscure the wood. The unequivocal success of the vaccine roll-out has created a positive feedback loop in the UK. It is notable that I no longer feel a compulsive nightly need to tweet much about vaccine hesitancy, the battle definitely feels like it is being won. We have become a serendipitous roadmap for how you do this. So here it is

- Message discipline from government, scientists and media. Don’t comment early, wait until data is clear. Address vaccine hesitancy with patience. Keep the big picture in mind.

- Vaccines do not need kid gloves. They are unbelievably safe in general. By applying kid gloves you raise concerns (why the kid gloves?). Trust your regulators and the regulatory process. Countries that ostentatiously delayed when they had the same data are now being viewed as ponderous and have spread undue concern. Regulators should be allowed to regulate.

- Don’t play vaccine nationalism. We really are only as strong as the weakest link on this one. A handful of countries going epidemic can kick off pandemic 2.0. We may not avoid this anyway but, either way, vaccine confidence needs to be rock solid. The UK’s decision to pledge excess vaccines to developing world is a step in the right direction but we need more than one half step. The WHO attempts to unite us all need serious buy-in.

- Roll out quickly and confidently and watch as momentum gathers and people start to see for themselves that the vaccines are safe.

Prominently vaccine hesitant countries where governments, commissions, journalists and even scientists are currently complicating what is a pretty simple picture, need to reflect on the success of countries like Israel and the UK. It is one of the few areas we can claim any success at all. But in the same way the UK has had to painfully learn lessons in every other area of Covid-19 management, we are currently succeeding here.

If leaders like Emmanuel Macron and Ursula von der Leyen continue to play tribal small politics with this, the effects will be long-lasting and profound. It is highly likely that we will end up all needing regular vaccination, and if we start off on the wrong foot internationally, recovering our balance is going to be possibly as painful for all of us, as the last year has been for the UK.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in