There has been an argument recently on Twitter about how to do nature-writing. Should it involve the self? Should it be poeticised? Has the oh-my-oh-me-ism of recent nature books got out of hand? Can one not see a blackbird now without considering the nature of consciousness and the tragedy of existence? In short, shouldn’t the nature writers calm down a bit and become ‘more honest’, as one contributor to this row put it?

Egregious sentences were quoted out of context. Angry and hate-filled expressions were used. The tone seemed wildly out of whack with the slightly technical question at hand — how to describe plants, places and animals — but was perhaps fuelled by something larger and more anxious. In the current state of things, how are we to meet the world? Is the apparently objective and ‘unselfed’ description the truest? Or would that not remove the one quality that can seem most central to the encounter, the sense that in nature there is the possibility of hearing, seeing and feeling a kind of significant connection with another reality that is often absent from the rest of life? Is nature best described as an it? Or through the lens of us-in-it?

Helen Gordon’s Notes from Deep Time (whose title rather pointedly resembles Robert Macfarlane’s recent, vast, baroque and richly self-engaged Underland: A Deep Time Journey) seems to be an experiment in the unselfed nature book. Gordon is a novelist and has edited an anthology about the writer’s life and craft and yet this is the most non-self-present book about an aspect of the natural world that I have read for years. In no way is it about her. Its method is journalistic: visit a scientist, discuss things with them and come home educated. Elizabeth Kolbert of the New Yorker is the master of this technique, and with great care and patient attention to correctness Gordon follows that path, hearing about ancient ice cores, the discovery of the nature of stratigraphy, the allure of meteorites, earthquakes and faults, chalky oceans, volcanoes, ammonites, the first plants, dinosaurs, the whole question of the Anthropocene and what might happen in the future to nuclear waste.

This is not unfamiliar territory and as well as Macfarlane many writers have been here before, including Richard Fortey, Neal Ascherson, Barry Lopez, John McPhee, Jacquetta Hawkes and Hugh Macdiarmid. The models are there for all sorts of sublime encounter — allowing the rocks to provide paths out of the ordinary — but Gordon holds back from any temptation that way. What she describes is all part of the real world, and for chapter after chapter the actual remains consistently actual. Her accounts of the scientists are respectful and respectable. Their beards and haircuts are described, but at no greater length than a sentence or two. We learn nothing of their lives or deeper motivations. ‘If people are interested,’ one of her scientists concludes about his own work, ‘then it’s worth doing.’

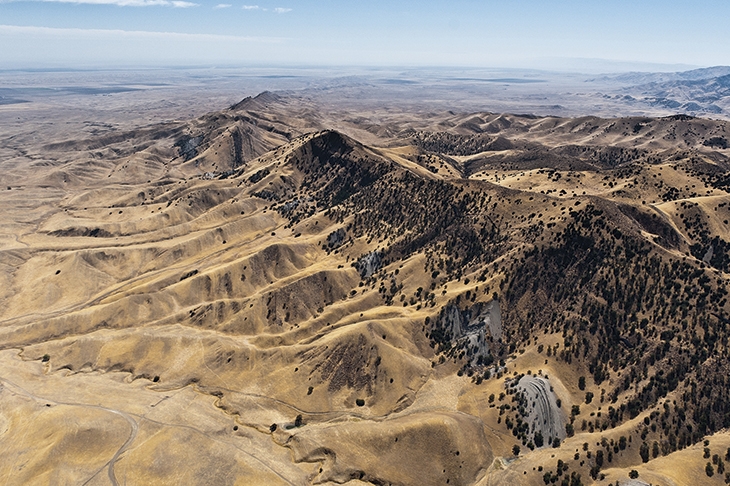

She looks up further information on the internet and watches YouTube videos. She sees where a volcano has erupted and might erupt in the future (but never one erupting now). She goes to the San Andreas Fault in California, where earthquakes have happened in the past, probably will in the future but aren’t happening now. Others inspect the fault from hang-gliders. She looks up at them from the ground.

This rigorous externality to the world she investigates means that her manner never tips in the stream of life. She doesn’t grieve for or lust after anything. She doesn’t do transcendence and has no drum to bang. Neither fear nor excitement, nor desire, nor loathing play their part. The method is consistently and carefully prosaic; one learns things about chalk and ice, maps and plants. There is no over-precise attention to the making of sentences. It is an almost scientific description of a science.

I fear I may be the wrong reader, because I hungered for the feeling of a transcribed reality, the vivid and the actual, a sense of embedded time, our own finitude, time’s lastingness, and the ways in which the tangible earth embodies a scale of being to which ours is of no significance. I longed for it to be more of an adventure, to read of the utter oddness of an earthquake or of the fearfulness of going deep underground, or the time-collapse on unpicking a fossil from its matrix for the first time in 200 million years.

It may be unkind to quote one writer in response to another, but I remembered words Christopher Stocks wrote recently. The noise on a beach of pebbles being ground together, he said, is both the sound of their being made and the sound of their being destroyed. He asked:

Could it be that, perhaps without really knowing why, we take pebbles home with us to preserve them? By taking pebbles away from the beach, we arrest an otherwise ineluctable process of decay. It’s as if we are trying to stop time in its tracks.

That thought is scarcely rational, but in its out-of-the-wayness does at least suggest a connection to the deep processes of the earth.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in