Richard Curtis’ iconic Love Actually airport scenes may fall on the wrong side of saccharine, but they capture something of the human story at the centre of the travel experience. As the Government pursues an ‘Australian-style’ hotel quarantine scheme for the UK’s borders, we should not lose sight of these human moments.

With the UK’s hospitals stretched to the limit and the population’s patience wearing thin, it is tempting to envy Australia, where images of seaside holidays and packed summer festivals filter out from the antipodes, shimmering like a desert mirage. Like many of its counterparts in the Asia-Pacific, Australia moved swiftly in the early phases of the pandemic to shut its borders, and imposed hotel quarantine systems for all arrivals. Now, it seems, its citizens are able to live a gilded life of unimaginable freedoms, while we here in Britain stagger our way through an endless winter of discontent.

We can all agree that the policing of Britain’s borders during the pandemic has been mind-bogglingly lax. The persistent absence of testing, tracing and home quarantine enforcement has been unacceptable. The proposed imposition of a hotel quarantine system, however, takes us from 0 to 100 in one fell swoop.

If closing the nation’s borders feels like a simple panacea, a false promise is being sold. We only need to look under the surface of Australia’s apparent success to begin to understand the tremendous logistical, social and economic price of such an endeavour.

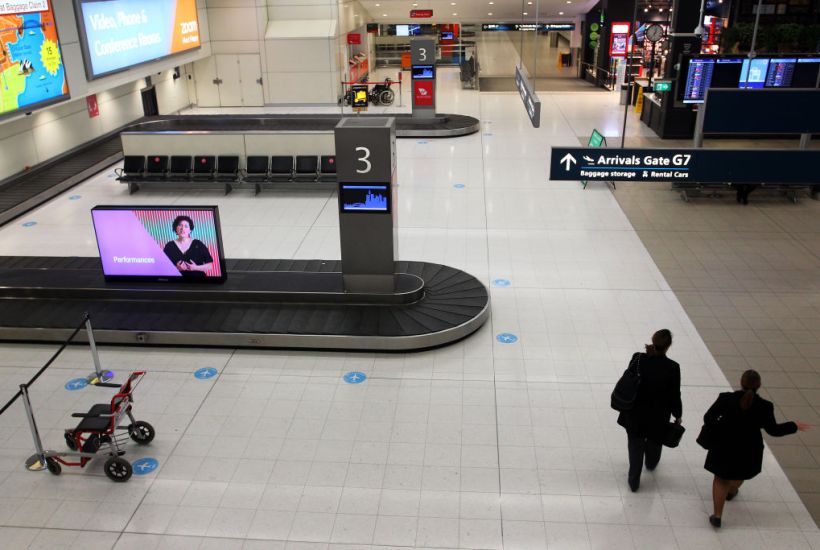

In Australia, the scale of the personnel required to manage the complex, militaristic quarantine system compelled its states to impose caps on the number of arrivals able to enter the country. These caps have, in turn, rendered commercial aviation unviable – driving up costs and cancellations, leaving around 40,000 Australian citizens stranded abroad, and many tens of thousands more, like me, separated indefinitely from our immediate families.

These marooned Australians are not hedonistic holiday-makers. They are citizens with a right enshrined by human rights law to return to their home country, and a human need to be reunited with their loved ones. Meanwhile, two of Australia’s most important industries – international education and tourism – stand on the brink. It is hard to see how the nation’s leaders will secure the consent to open up again. A nation once proud of its internationalism increasingly surveys the world with fear and suspicion.

This dirty underbelly of Australia’s quarantine system has received scarce attention in the UK. I’m sure many Britons would find something satisfying in watching the glitzy influencers camping out in Dubai being forced to TikTok from the Heathrow Travelodge. But hotel quarantine is not simply about clipping the wings of selfish sun-seekers. It is a policy that will bear asymmetrical costs on those for whom mobility is an essential component of their work or family life.

Britain is an open and connected global nation, with an increasingly multicultural population whose links stretch across the seas. Australia’s system – particularly harsh compared to its neighbours – reveals something unique about the nation’s character, and something practical about its geographical isolation. The zeal with which Australia’s population has embraced its isolation reflects the stimulation of a reflex muscle that would be difficult to reconcile with our own ambitions to become ‘a truly Global Britain’.

The UK Government may well conclude that the potential costs of hotel quarantine are worth bearing. The arguments for a partial, adaptable scheme focused on reducing the introduction of new mutations are strong. But it would be folly to pursue the wholesale carbon copy of a system that has precipitated such extraordinary failings – especially when we have never really invested in the enforcement of a more liberal system better-suited to our needs.

If its day must come, simple steps can be taken to improve hotel quarantine. A compassionate and flexible exemptions scheme must be put in place, and the mental and physical health of arrivals provided for. A clear roadmap should be prepared to manage the transition out. It may be insanity to repeat our failures, but we will find no greater salvation in repeating the blunders of others.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in