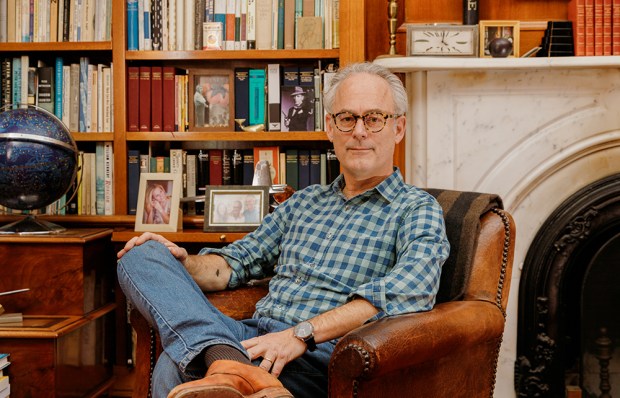

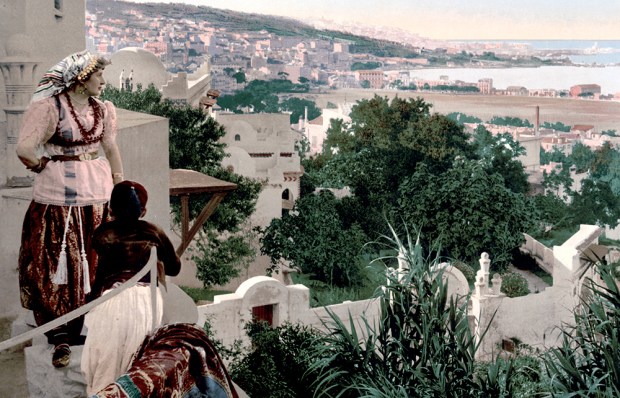

Thanks to the Booker Prize, Richard Flanagan is probably the only Tasmanian novelist British readers are likely to have heard of. His reworking of the life of the Australian hero ‘Weary’ Dunlop, a doctor who became a prisoner of war on the notorious Burma Death Railway, in The Narrow Road to the Deep North was a winner of a traditional kind of literary storyteller that has recently become extinct.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in