If 2020 has given us something to talk about other than Covid, it’s been history — and, more precisely, to whom history belongs and how we’ve chosen to define it. Well into the modern era, the philosopher Thomas Carlyle’s definition of the subject as ‘the biography of great men’, seems to endure. Most remember their school history lessons as a force-fed diet of monarchs’ names, battles and key dates, or as a narrative about palace-dwelling elites whose experiences seemed utterly removed from reality. It is undoubtedly why the subject in its most uncut Victorian form can seem so unpalatable to the general public.

Conversely, it also goes a long way to explaining the popularity of the BBC hit series Who Do You Think You Are?, now in its 17th season. While the programme’s success can partly be attributed to the celebrity pedigrees laid out for inspection, the power of the series’ subversive message shouldn’t be underestimated: no matter who one is or what one’s origins, history has played a role in shaping all of our lives. Removed from its mountain top and presented in this form, grass-roots history on a micro level can be everything we believed history wasn’t — personal, intimate, surprising and, dare one even suggest it, exciting.

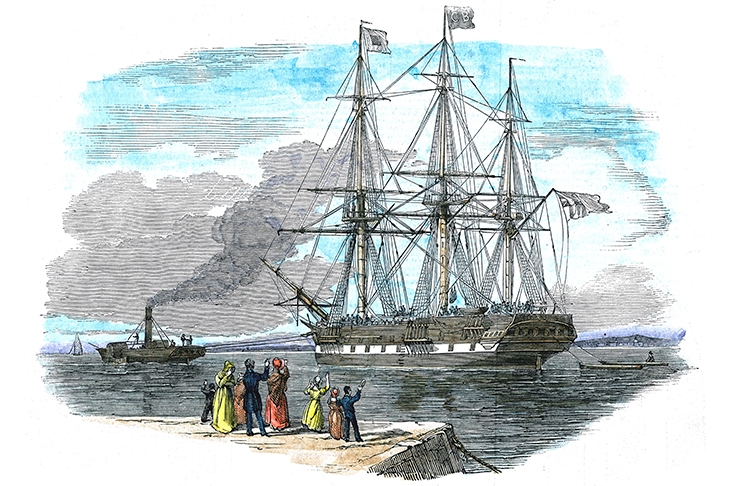

If ever there was a time for Carmen Callil’s pensive and lyrical telling of her family’s humble history it is now. Oh Happy Day! masquerades as a small narrative about Callil’s impoverished ancestors, but unfolds into an epic examination of the Victorian era, its corrosive mores, oppressive rules, its well-intentioned ideologies and punitive institutions. We are taken through the industrial slums of the Midlands, into the mouldering hovels of cottage workers who toiled through sickness and starvation. We are thrown into the draconian machinery of the workhouse. We are manhandled by the justice system for minor misdemeanours. We are lashed on a prison ship and worked like a dog on the red Australian soil. Our tour guides through this Dantean hell are not the usual reforming politicians or literary giants, preaching their observations to us from a safe distance, but, appropriately, the ‘Nobodies’ of Eduardo Galeano’s poem, ‘Who do not appear in the history of the world, but in the police blotter or the local paper’.

Callil weaves the three stories of her Leicestershire and Lincolnshire ancestors through this rich but darkly coloured 19th-century tapestry. The first strand belongs to Sary Lacey, her three-times great grandmother who was born a Georgian in England and died a Victorian in Australia. Like so many daughters of the labouring class, Sary came into the world illegitimate, and went on to give birth to children out of wedlock. One of those children was by the Dickensianly named George Conquest, a canal worker who had the misfortune to get caught stealing some hemp from a boat. A young, strong and able man, Conquest made a perfect candidate for transportation to Australia, which left the unmarried Sary to fend for herself and their daughter, Eliza, who died young.

Callil traces the forced footsteps of George through the penal system, aboard a prison hulk and eventually to the Melbourne estate where he served his seven years hard labour under the searing anti-podean sun. But it was here, in the employment of the relatively sympathetic Dr David Reid, that Conquest’s fortunes began to turn. Between the goldfields and a carting business, Conquest was able to earn an income better than any he could have imagined possessing in England. By 1858 he was the owner of six houses. His new wealth enabled several of his relations as well as Sary and her son to emigrate to Australia. For them, as well as for another branch of Callil’s workhouse-confined family, the Brookses, both transportation and emigration to Australia proved to be their happy day.

However, Callil is correct to add in her epilogue that it certainly wasn’t a happy day for the indigenous population of Australia, who were forcibly displaced by the British government in a programme to steal their land and eradicate their way of life. She makes a heartfelt plea for schools to incorporate Britain’s ugly ‘warts-and-all history’ when teaching about the empire, asserting that the ‘denial of historical villainies is no way to bind a people’. Callil provides a fascinating and emotive case study of just what those villainies were, both at home and abroad.

Past historians have argued that as we know so little about history’s disenfranchised people it is an impossible task to reconstruct their narratives. With this triumphant family memoir, not only has Callil proved this to be untrue, but she has shown how these voices might be restored to the record, and why, for the integrity of our national story, we must do it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in