At the beginning of the Covid crisis, some expressed the hope that a pandemic might at least bring a divided country back together. Instead, public discourse descended to new levels of bitterness as a fresh schism replaced that caused by Brexit. On one side were those who thought tens of thousands would die because government action was too slow and half-hearted, and on the other, those who thought lockdown to be an over-reaction that inflicted grave damage on our economy and society.

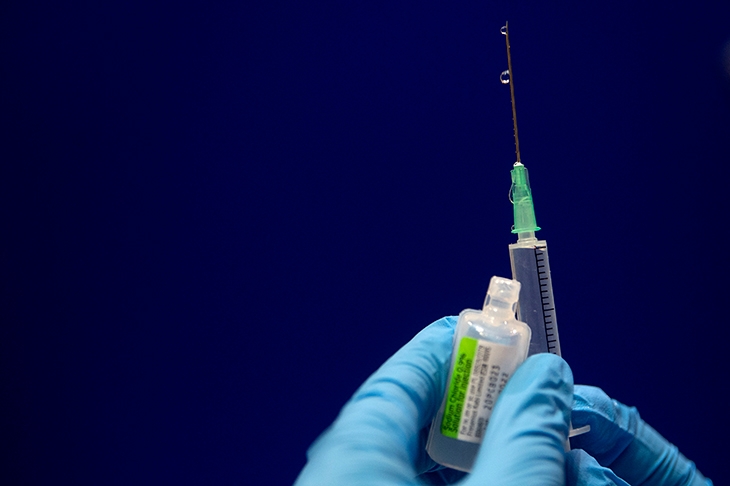

Both sides ought now to be able to agree that this week marks a significant turning point in the pandemic. The first shot of an approved Covid vaccine to be administered in a public programme anywhere in the world was given to Margaret Keenan, a 90-year-old woman in a Coventry hospital. There are still some uncertainties: we don’t yet know how good the vaccine is at preventing transmission of the virus, or how long immunity will last.

But as far we can tell from the phase 3 trial involving more than 40,000 volunteers, the Pfizer is 95 per cent effective at preventing infection with the Sars-CoV-2 virus. While a small number of the volunteers given the vaccine did show signs of infection, only one went on to suffer serious illness. As soon as the most vulnerable elderly groups in the population have received their two jabs, the vaccine should start to make a very big difference to the progress of the disease.

For all the government’s many failures during the Covid crisis, ministers deserve their moment in the sun. Whether it was foresight or a gamble that paid off, the government’s decision to purchase a portfolio of vaccinations early on in their development has given Britain a head start in recovery. We can hope that life will return to normal before any other country, certainly in Europe or North America. That is something to be celebrated, whatever your stance on lockdowns or travel bans.

That said, there is still a small but vociferous minority who are not celebrating the arrival of a vaccine and who will refuse a jab. They are against all vaccines, believing them to be some dark conspiracy with hushed-up side effects. The concerns of this group can be dismissed. Those with a general objection to vaccination ignore the evidence that it has transformed health outcomes. The eradication of smallpox in 1980, for example, is a crowning achievement.

But there is another group whose concerns should not be brushed aside: those who believe the development of the vaccine has been rushed. Why, it’s asked, does it normally take ten years for a vaccine to be developed but this time one arrived just nine months after the virus? Ministers should welcome such questions, which offer the opportunity to explain how the science has advanced, the rigorous nature of the regulation — and just why we can be so confident in vaccine safety now.

Under the old technology, it took time to modify, grow and inactivate a virus (or its proteins) to be included in a vaccine. An inactive or weakened version of the virus was injected into the body in the hope of generating an immune response but not a dangerous infection or reaction. The Pfizer vaccine contains no virus and no proteins. It uses innovative gene-based technology called messenger RNA, which stimulates the body to respond to Covid-19, prepping the immune system without nasties. This is a breakthrough that once proven to work can be repurposed for other infectious illnesses, and perhaps even cancer and heart disease.

It is demonstrably untrue to say that the Covid-19 vaccine trials have been skimped or undertaken in a less rigorous manner than normal. The trials have involved far more volunteers than for most jabs. Side effects have been properly noted, and all participants in the trials will continue to be observed. Procedures have been accelerated, but through running trials in parallel rather than series. This was because the stakes were huge and vaccine approval could not be undertaken in a rush. So, instead, it started early.

Covid-19 is far from the deadliest disease to strike mankind, but its infectiousness has ensured massive economic disruption. The quickest way out of the crisis is for as many people as possible to take the vaccine, whether or not they feel vulnerable.

Unless the government does something to undermine trust and goodwill — such as issuing ‘vaccine passports’ — the vaccine should be a success. The power and influence of the anti-vaxxer lobby is vastly overstated. Vaccination rates of British children for common childhood diseases are above 90 per cent. If 90 per cent of UK adults take the vaccine it should be more than enough to bring the epidemic to an end.

It would be too much, however, to hope that the vaccine will put an end to recriminations, which will go on for years regardless. But we can be confident that by the second quarter of next year it will lead to a huge improvement in life in Britain and the world.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in