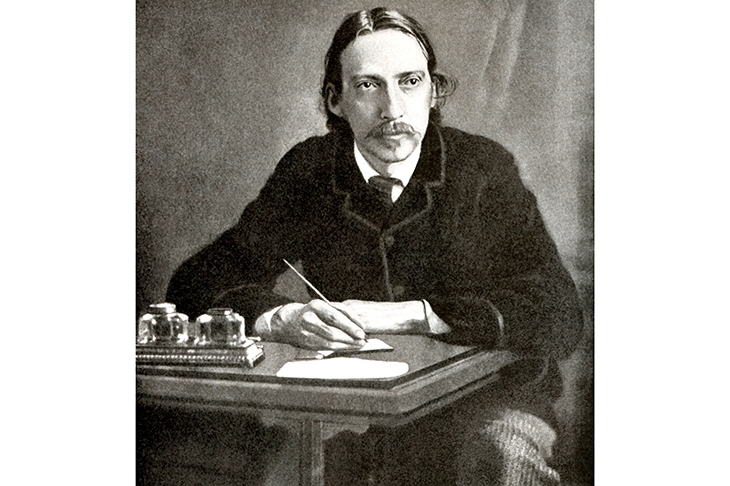

This book has appeared with no fuss or fanfare and yet by any account it is something of a scoop. For here, published for the first time, is the correspondence between J.M. Barrie and Robert Louis Stevenson, revealing one of the most intriguing literary bromances of the 19th century.

The existence of the letters is well documented. In the early 1890s, gossip columns were agog with the news that two of the most popular writers of the day were corresponding, with Barrie reported to be writing ‘reams of letters’ to Stevenson. But while Stevenson’s letters to Barrie were published after the former’s death, Barrie’s letters to Stevenson never surfaced. It is thanks to their recent discovery by Michael Shaw, an academic at the University of Stirling, that we can now read the correspondence in full.

The first letter is dated February 1892, when Stevenson was at the height of his fame, while Barrie, ten years his junior, was already known for popular books such as The Little Minister, but yet to write Peter Pan. As Shaw notes in his informative introduction, one of the key themes in the letters is the authors’ ‘respect for each other’s “genius”’. But what is fascinating is the shift in authority. In the earlier letters, Stevenson takes the role of literary mentor to his ‘brither Scot’, doling out advice about plots and characterisation: ‘You should never write about anybody until you persuade yourself at least for the moment that you love him,’ is one nugget of wisdom. But as Stevenson reads more of Barrie’s work, his tone changes. He writes to him in December 1892, after reading Barrie’s novel A Window in Thrums: ‘I am a capable artist; but it begins to look to me as if you were a man of genius.’ Some of Barrie’s skills, Stevenson notes, are ‘beyond my frontier line’.

But it is Barrie’s letters that give the correspondence its peculiar piquancy. The Victorian critic Andrew Lang noted: ‘Stevenson possessed, more than any man I ever met, the power of making other men fall in love with him’ — and Barrie appears to have been no exception. In one letter, responding to Stevenson’s praise, he speaks of his ‘sufficient sense to continue to sit at your feet’. Upon hearing that Stevenson had fallen ill, Barrie writes: ‘To be blunt I have discovered (have suspected it for some time) that I love you, and if you had been a woman —.’ And he ends one epistle: ‘I wish I was this letter now and that I might see you in the flesh.’

On the one hand their intimacy seems surprising, given that the two authors never met. They both attended Edinburgh University in the 1870s, but by the time they started corresponding Stevenson had settled in Samoa while Barrie was living between Angus and London. As Shaw points out, however, it is this distance that lends the correspondence its charm. In one letter, pressing for information on Barrie’s next book, Stevenson writes: ‘No harm in telling me; I am too far off to be indiscreet […] I am rushes by the riverside, and the stream is in Babylon; breathe your secrets to me fearlessly.’ Barrie accepts this logic. To Stevenson, he writes, he can reveal ‘the real JMB who has been so far carefully concealed from his “intimate friends”’.

They also enjoy a bit of literary back-stabbing. Stevenson finds Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles ‘languid and false to every fact and principle of human nature’, while Barrie, a friend of Hardy, finds the novel ‘wrong-headed’, and Angel Clare the ‘greatest prig in fiction’. As for ‘the new lady novelists’, they can for the most part, according to Barrie, ‘be divided into those who shriek because some one has seduced them and those who shriek because no one will seduce them’.

Stevenson repeatedly urges Barrie to make the journey to Samoa (‘Your soul’s health is in it. You will never do the great book… till you come’); but Barrie confides that the reason he cannot travel, which he dares not tell his friends, is his ‘passion for my mother and my young sister’. So instead he is left to imagine Stevenson ‘in a suit of bananas… enticing the monkeys to fling cocoanuts at you, which is my notion of life in Samoa’.

Shaw draws parallels between Samoa and the Neverland of Peter Pan, arguing that Barrie associated Stevenson with the spirit of youth: ‘Just as Pan feels sorrow for leaving his mother, Barrie expressed guilt at the thought of leaving his own mother when he considered visiting Stevenson in Samoa.’ Peter Pan has inspired a torrent of academic theories, and Barrie’s letters will doubtless give rise to more. But who knows what else we might have learned had the correspondence not abruptly ended in 1894 when Stevenson died, aged 44, after suffering a suspected brain haemorrhage while making mayonnaise. As Barrie wrote shortly afterwards to Stevenson’s stepson: ‘To me it is as if a bit of myself had died, the romantic part, which was for ever running after him.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in