‘Free Tibet!’ used to be a rallying cry for Hollywood A-listers and rock stars. Richard Gere hung out with the Dalai Lama; the Beastie Boys organised a series of giant benefit concerts. Global attention has shifted to other regions suffocating under the jackboot of the Chinese Communist party (CCP), notably Xinjiang and Hong Kong. But the Tibetans’ fight for freedom continues — though only just.

Since 2009, 156 Tibetans have set themselves alight in protest at China’s repressive policies. Nearly a third of them are from Ngaba, a small county on the south-eastern edge of the vast Tibetan plateau. Ngaba (pronounced Nabba and known as Aba in Chinese) is home to 73,000 citizens and a mind-boggling 50,000 security personnel. When the immolations began, the authorities unplugged the internet, severed all communications and set up checkpoints to keep out snooping reporters. Barbara Demick, best known for her prize-winning account of life in a North Korean city, was one of the few who sneaked in.

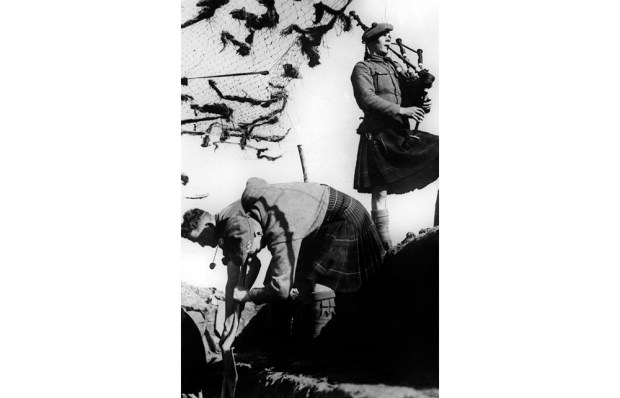

She made three trips to Ngaba, where the military presence reminded her of wartime Baghdad and the level of fear of North Korea. But the meat of the book is an oral history of the lives of local people under Chinese occupation, stitched together from exhaustive interviews with Tibetans living in exile. She interweaves their memories into a novelistic narrative, using Ngaba as a window on to the broader history of modern Tibet.

The CCP insists that Tibet has been a part of China for 800 years, but it was only ever nominally under Beijing’s control. After the Qing empire collapsed in 1911, Tibet established its own national flag, currency and travel documents. When the Red Army first arrived on the grasslands near Ngaba in the 1930s, they presumed they had left China. Chairman Mao certainly felt that way, later describing his troops’ confiscation of the locals’ food as ‘our only foreign debt’. In the Buddhist temples that dot Tibet, his starving soldiers found devotional figurines made of barley flour and butter. They set about literally ‘eating the Buddha’, giving this book its title.

Soon after the invasion of Tibet in 1950, the CCP launched a series of ill-conceived schemes to rid Tibetan society of its feudal past. Tibetans refer to the catastrophic ‘Democratic Reforms’ of 1958 as the time ‘when the sky and earth changed places’. Nobles were thrown off their land, monks turfed out of monasteries and ordinary people banned from cooking their own food. Starving children picked seeds from horse manure or collected bones — sheep, yak, dog, even human — to boil down for soup. In 1959, the young Dalai Lama fled Lhasa for exile in northern India, settling in the crumbling colonial hill retreat of Dharamsala.

Another shocking fact: Chinese bombers flew thousands of sorties, obliterating villages and monasteries in what was supposedly their own country. Demick puts the death toll in the 1950s and early 1960s at around 300,000, perhaps a quarter of the Tibetan population. While the whole of China suffered terribly under the twin calamities of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, for the Tibetans ‘the abuses started earlier and lasted longer’. One of the early victims was Gonpo, the last princess of Ngaba. When her palace was burnt down and parents killed, she was forced to assimilate into Chinese society, singing paeans to the ‘peaceful liberalisation’ of Tibet.

The 1980s initially brought hope of a freer future, but when the young intellectual Tsegyam was caught distributing ‘Free Tibet’ posters he was jailed. After his release in 1990, he sneaked over the border to India, becoming the Dalai Lama’s private secretary. Two decades later he was joined by Tsepey, a handsome dancer who was propelled to join the fight after picking a dead girl out of a ditch, shot when a crackdown ahead of the Beijing Olympics sparked a violent uprising. After the arrest of 600 monks, Ngaba transformed into ‘the undisputed world capital of self-immolations’.

Three generations of Ngaba residents have suffered at the hands of the CCP, and Demick’s meticulous and tenaciously researched book tells their stories for the first time. But it is neither a dissidents’ rant nor a misery memoir. We hear about an entrepreneur who grows rich through trading cheap goods across the Tibetan plateau, and a sulky teenager who’d rather watch Chinese TV dramas than worry about politics. Demick acknowledges the falling population of exiles in Dharamsala and the queues of unemployed Tibetans seeking passports at the Chinese embassy in Delhi. The economic gains Chinese development have brought to Tibet are ‘not all propaganda’.

Tibetans want the same infrastructure, technology, education and jobs as everyone else. They also want to keep their language, culture and religion. ‘I have everything I might possibly want in life,’ says one affluent businessman in Ngaba, ‘but my freedom.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in