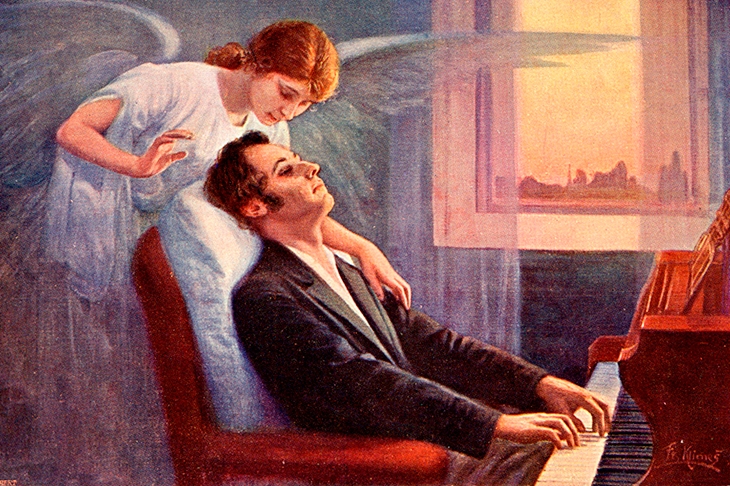

There’s a scene early on in A Song to Remember — Charles Vidor’s clunky Technicolor film of 1945 — in which the young Frédéric Chopin (Cornel Wilde) provides background music for a banquet hosted by Count Wyszynska in his Warsaw palace, plates of rubbery pig and candy-coloured vegetables in heady supply. Chopin plays his own Fantaisie-Impromptu, five years or so before composing it, and then, having insulted the Russian governor of Poland (‘I do not play for tsarist butchers!’), he avoids arrest by hastily rowing to Paris, so it seems, dressed like a military cadet.

Our real-life hero has borne an awful lot since his premature death in 1849, though this particular film — with its mushy soundtrack, red-cheeked wholesomeness and hateful portrayal of the brilliant George Sand — is a definite nadir. A Song to Remember was not even the only picture on this very subject in these decades: the same troop of characters gurns its way through Henry Roussel’s silent film La valse de l’adieu (1928), released nine years after the Germans had first raised their flag with Nocturno der Liebe.

It seems at the very least ironic that a figure as blurry as Chopin during his lifetime should be brought into keen focus following his death. Probably it’s this very blurriness that encourages such ventures: documentation can be imagination’s most unforgiving suitor, after all. So people continue to foist on Chopin their own fantasies and desires, some more lurid than others. And in the same way that the meaning of Chopin and his music has shifted in the 170 years since his death, so too have depictions of him in popular culture mutated.

Nor is it simply in popular culture. The implementation of railway lines throughout Europe during Chopin’s lifetime initiated a slow homogenisation in the perception and performance of his music — a process intensified by recordings in the next century, and the internet in the one that followed. Yet before this homogeneity there were fiercely delineated national schools of Chopin playing: the Russian Anton Rubinstein’s approach to Chopin — monumental, muscular, imperious — could not be more different from the French Alfred Cortot’s wayward, intimate readings.

Annik LaFarge shares none of Vidor’s licence or excesses, none of Roussel’s silent-film theatrics. The clue is in her subtitle, for she has indeed written an intensely personal journey through time, place and politics. Using the March funèbre from Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2 as a useful companion, LaFarge constructs a sort of travel diary through which to explore what this piece meant to Chopin (politics and place) and what it means today (time). Along the way she takes in jazz players’ riffing on Chopin; Cole Porter’s sucker-punch harmonic juxtapositions; Henry Purcell’s solemn, sparse response to the death of Queen Mary; André Gide’s long and ultimately consummated relationship with Chopin and his music (‘Chopin proposes, supposes, insinuates, seduces, persuades; he almost never asserts’, which was Chopin’s explanation of how he approached the variations in Beethoven’s Sonata No. 12); contemporary video games; political subjugation and revolution; the fate of Paderewski’s heart (mirroring that of Chopin’s, though the parallel is left unexplored in this text, a curious omission); and the sheer audacity of Sand’s one-of-a-kind-ness.

LaFarge is weighty (and great) on the importance and singularity of Chopin’s friend and patron Astolphe de Custine, though she’s not right on the significance of the small local piano Chopin had with him in his primitive quarters in Majorca. (Though LaFarge is streets ahead of Vidor, who places Chopin and Sand in an opulent Majorcan villa, replete with gold candlesticks, beautiful tapestries, a gilt-detailed piano and heavy drapes.) It’s certainly true that for a few weeks before Chopin dispatched the manuscripts of the Sonata, the Preludes and a few more things besides he had access to the Pleyel instrument that had made its way reluctantly from Paris to Majorca, yet in the months prior — the time in which he chipped away at these astonishing pieces — he worked methodically (his wont) on the local piano.

Other quibbles? Well there’s a scene in which a young pianist inside these same quarters communes a little too emotionally with his hero. Also, it remains unclear whether it was Chopin or Sand who suggested they make their relationship chaste, so LaFarge’s assertion that it was the latter is at best half true. Yet mostly she has a good eye and ear for her subject, choosing her anecdotes with care. When Józef Elsner, the young Chopin’s teacher, is asked why he gives his pupil such a free hand, he replies: ‘Leave him in peace. His is an extraordinary path, for he has an extraordinary gift. He does not follow the old rules, because he seeks those of his own.’ Though this sounds like a corny line from A Song to Remember, it actually comes from a letter Elsner wrote to another of his pupils. We live today with the glorious ramifications of this gentle rebuke.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in