What are we to make of the decision by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to grant emergency use authorisation for blood plasma treatment of Covid-19? Is this a medical breakthrough or a dangerous move forced on it by a desperate president who sees his electoral chances slipping away unless he somehow gets on top of the crisis over the next few weeks?

It goes without saying that the approval of drugs ought to be above partisan politics. Introducing novel drugs into everyday use has the potential to bring a huge amount of good – but also the potential to cause a great deal of harm. The only satisfactory way for such decisions to be made is through an independent body that is strong enough to resist pressure from politicians, pharmaceutical companies or anyone else.

That said, is there any evidence – apart from the timing of the FDA’s announcement – that the FDA has allowed itself to be leant on? The timing, it should be noted, is not an insignificant matter. It comes a day after Donald Trump called on the body to approve the treatment and accused it of delaying the approval of Covid vaccines and treatments.

But it would be a serious charge to levy against the organisation – that it caved into an off-the-cuff remark by the President. As for the timing, one wonders whether it was the other way around: that the President had advanced knowledge of the FDA’s announcement and decided to try to claim credit for it. Or it could be pure coincidence.

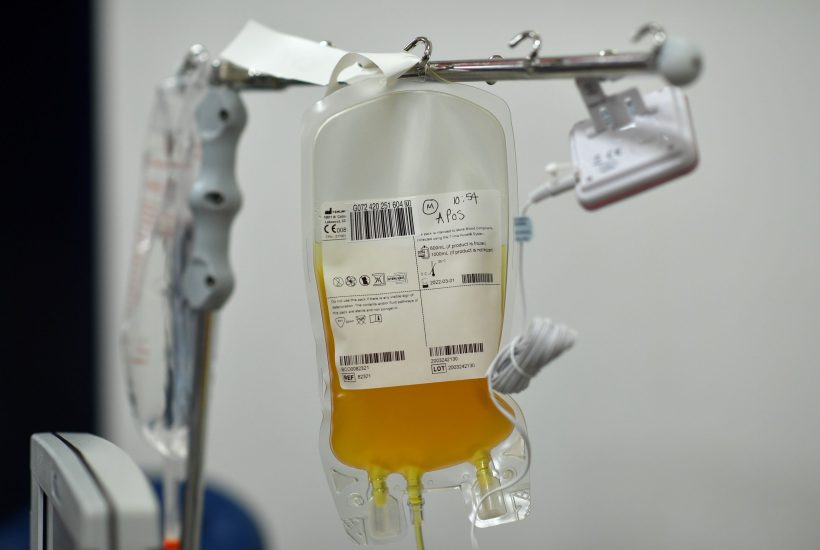

The issue with plasma treatment – which involves infusing Covid patients with the blood plasma of patients who have recovered from Covid-19, and whose blood contains antibodies to the virus which causes it – is that data from randomised control trials in incomplete. However, the treatment has already been given to 70,000 Americans and – according to the FDA – has shown effectiveness. In people under the age of 80 who have been hospitalised but not put on a ventilator, it has improved the survival rate by 35 per cent.

Should we have to wait, in the midst of a pandemic, for full results from randomised control trials before authorising its use in hospitals? There is a very big difference between authorising a drug for use with a limited number of people who are already desperately ill, and authorising, say, a vaccine that is going to be administered to almost a country’s entire population. A much higher level of risk is appropriate in the first instance than in the second. If, say, a treatment for desperately-ill people killed 1 per cent of those to whom it was administered, that might be a tolerable price to pay in return for the chance of saving other lives. On the other hand, if a vaccine killed 1 per cent of people to whom it was given, it would be a disaster – responsible for more deaths than Covid-19 itself. Such a problem has arisen before, in 1976, when millions of US citizens were given a hurried-approved vaccine for H1N1 swine flu – and the vaccine was found to cause the paralysing condition Guillain-Barre syndrome in some cases.

This morning, Trump has indeed called for emergency authorisation of the Covid vaccine being developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca so that it might be in use before November’s election. While stage one and stage two trials have shown the vaccine to be safe, the stage three trials on a much larger sample of volunteers in the community have yet to be completed. If the FDA rolls over on that one, people really will quite reasonably start to ask whether it is under Donald Trump’s thumb, but the money is on the FDA holding fire until the full trials have been completed.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in