I sometimes pick up some food at Tesco for an 86-year-old pensioner who lives a few streets over. At the weekend, I brought him milk and cornflakes. He opened his front door; I put the bags down, retreated the required two metres, but when I looked up he was in tears. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said, quietly. ‘I’m just so lonely at the moment.’

Should I have moved closer, put my arm around him? At the moment the risk of passing on the virus is low in London. I’ve had the bug (I think) and I used hand gel after leaving the supermarket. It’s been said of the recent protests that distancing is irrelevant because racism is a deadlier epidemic than Covid. If that’s true of racism, isn’t it also true of loneliness in the old?

Perhaps I should have hugged my friend. I didn’t. Cowardice and uncertainty kept me stuck on the top step. I just stood there grimacing like a vicar, trying to show that I felt his pain and saying: ‘I’m so sorry.’

The truth is, until that moment, I hadn’t much felt his pain. I’d read the astonishing surveys that say the old are faring weirdly better than the young. Although coronavirus is catastrophic for the very old and for the most part a pretty minor bug for the very young, nonetheless 65 per cent of those aged 16 to 19 say their wellbeing has been affected, vs only 34 per cent of over–seventies. Go figure. At any rate, I’d given myself licence not to worry, quite forgetting all the elderly out of reach of polls.

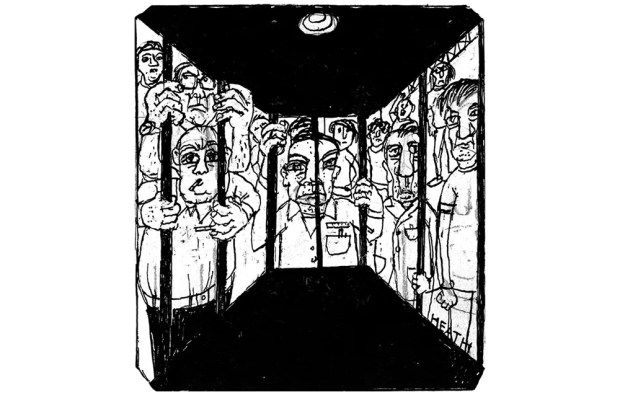

Just as pre-existing conditions can exacerbate the virus, so almost every downside of an unlucky old age has been exacerbated by lockdown. If you live alone (that’s more than a million older men and women), you’ve been cut off from contact: no cafés, churches, social clubs. If you’ve got no children (another million) there’s no Zoom tuition from grandchildren, perhaps no one to Zoom either. Those old men and women only just able to cope, on the brink of toppling into care, like 10p pieces in the coin-pusher arcade game — do they feature in the stats? I don’t know how they could. I’m quite sure my pensioner friend wouldn’t answer the phone to a pollster, and no one’s knocking door-to-door in this day and age. And what about the deaf? Almost 70 per cent of over–seventies find it hard to hear. I’m not even sure, come to think of it, that many frightened nonagenarians ever see the kind notices saying ‘Call this number for help if you’re shielding’ — because they’re shielding.

Most things about lockdown are immeasurably worse for the old. Operations on cataracts, knees and hip joints: all postponed. Dentists closed, GPs only available on the phone, if you’ve ears to hear. Pensioners have been told that it’s vital to get outdoors for both body and mind — be more like Captain Tom. But what if you fall? Who’d want to end up in hospital now? An 84-year-old friend on my street who is profoundly deaf tells me that masks are a disaster if you rely on lip-reading. She says it’s awful not to be able to see what’s being said. She’s lonely too, she says. Calls to the Silver Line, our only helpline for oldies, have risen by a third.

The country singer John Prine died of coronavirus in April, aged 73. When he was only twenty-odd he wrote the hit ‘Hello In There’: ‘You know that old trees just grow stronger/ And old rivers grow wilder ev’ry day/ Old people just grow lonesome/ Waiting for someone to say, “Hello in there, hello”.’ I’ve come to think of John Prine as the patron saint of the corona era.

Friends of my own age have for the most part loved lockdown. It’s nice having the children home again, they say, and they never knew how easy it was to order organic vegetables online. But what if you’re not online? More than four million people over 65 have never used the internet. And what if you’re unsteady on your pins? This distancing and queueing looks set to continue. It can sometimes take 20 minutes to get into my local Sainsbury’s. We queuers pass the time glaring through the window at anyone dawdling, clouding the glass with viral fog. As summer drifts on, the zimmers will emerge again. Will the young think to give up their place in the queue?

I’m often told how ethical the kids are, how upright, sober and engaged with serious issues like climate change. But I’m haunted by a train ride from Edinburgh to London a few years ago in which four twentysomethings plain refused to give their seats up to a woman in her nineties. With some difficulty, balanced on her stick, she took her ticket out of a pocket and showed the boys her seat reservation. ‘But didn’t you hear the announcement?’ said one. ‘Ticket reservations have been suspended.’ It still keeps me up at night. I see #BeKind on Twitter, I see it tattooed on the forearms of the under-thirties; is it just an instruction for others?

We’re all going to be on the streets together soon. Black, white, male, female, old and young. And everyone’s biggest concern will be for the youth. Jobs will be in short supply, the future uncertain. Polly Toynbee argued last month that the triple-lock state pension should end: ‘We older people should be grateful that younger generations accepted extraordinary constraints on their freedom and damage to their prospects mainly to protect us, not them. From now on all decisions should put them first.’

What about another quid pro quo: if the old will volunteer to risk their lives and sacrifice their pensions for the young — and they will — what about the kids return the favour and pair up with the old who aren’t coping; the childless and the left-behind? Shop for them, deliver a paper, help them switch on their iPads.

So if you’re wandering down the street sometime/ And spot some hollow ancient eyes/ Please don’t just pass them by and stare/ As if you didn’t care, say hello in there. Hello.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in