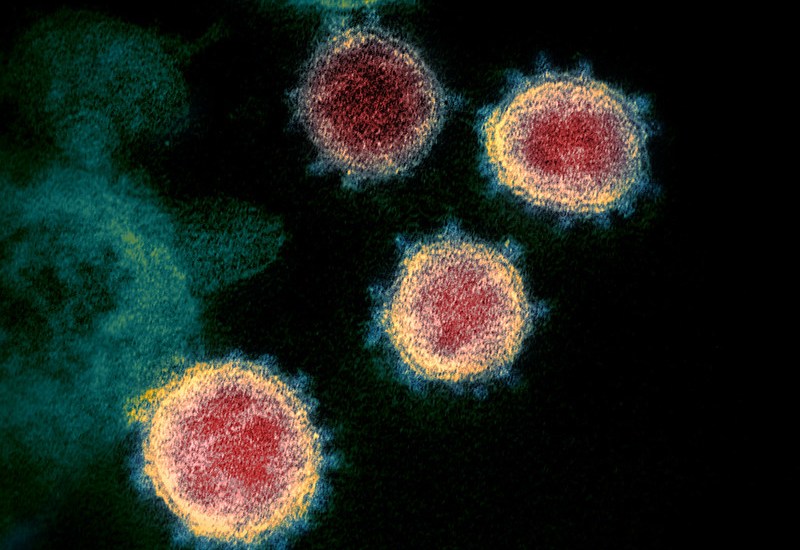

Over the last few months, the management of severe Covid-19 cases has effectively been turned on its head. At first, reports from China and Italy, coupled with initial guidance from the World Health Organisation (WHO), had doctors preparing for acutely ill and breathless patients whose lungs were being starved of oxygen.

The natural reaction of any self-respecting intensivist once oxygen levels drop, particularly if the diagnosis is a new and potentially fatal virus, is to put the person on a ventilator to give their immune system time to fight the infection. But it quickly became clear that with Covid, the pattern was somewhat different. The danger was not a direct coronavirus attack on the lung itself but a disordered immune system response to it. This is significant, and it may mean that we should give much greater prominence to the optimisation of our general health and regulation of the response to infection.

The initial rush to manufacture ventilators around the world produced machines which are now unneeded for Covid patients who appear often able to withstand lower oxygen levels better than originally expected. Those that did deteriorate were possibly not helped by artificial breathing. Their lungs were liable to become stiffer and more swollen and their oxygen levels failed to improve. Soon there was a subtle change in treatment and ventilators became a treatment of absolute last resort. Instead, it appeared that the virus was triggering an uncoordinated upsurge of immune activity, something termed Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome.

The recently discovered benefits of an immune suppressant (dexamethasone) for treating severe lung infection associated with the coronavirus entirely fits this pattern. The initial hypothesis that the body needs a heightened immune response to fight the virus was incorrect. As also shown by anti-viral agent Remdesivir, what has actually proved most useful is the lowering of the immune system and resultant reduction in swelling that is the main effect of this steroid medication.

Further possible evidence of this comes from the initial success of the Oxford group in finding their vaccine stimulates a significant immune response from the virus. Their findings show that the virus has the potential to heighten the immune system. This is encouraging in terms of providing immunity but a possible danger for those who have other medical issues or are elderly, and are less able to control their immune system. At this stage, much is unconfirmed. But it should be noted that the promising Phase one vaccine results came from fit and well volunteers. The real challenge for the vaccine will be how it fares in the Phase Three study, particularly amongst older people with other significant medical conditions – exactly the demographic who have suffered most in this pandemic.

Another potentially fascinating medical discovery came earlier this week with the unconfirmed finding that an immune modulator medication – interferon-beta – may also improve outcomes involving Covid-related severe respiratory involvement. Caution needs to be attached to this news, as it came from a pharmaceutical pre-announcement of the results of a small trial which has not yet been published. But again, it potentially reinforces the message that better control or regulation of the immune system is beneficial, and that in some of the most serious cases, the issue is not direct attack from the virus itself but its triggering of an abnormal increased immune response. Put simply, there is an argument that we should be looking at fortifying our immune systems.

As a doctor who sees a lot of people with what are termed autoimmune disorders (diseases in which the body effectively attacks itself) there are several common risk factors, chiefly poor general health like obesity and smoking, and chronically low levels of Vitamin D. To my mind there has not been enough guidance and emphasis from the scientific advisors and the Department of Health on these factors with regards to Covid-19. NICE, the main review body of the NHS, did look at the issue of Vitamin D deficiency and concluded there was no definite link to severity of Covid-19. But this analysis was complicated by a paucity of clinical trials and problems with design. This is almost inevitable: designing a study on a substance we derive mainly from sunlight is fraught with difficulty.

Modern medical practice in several autoimmune diseases now is to simply accept that getting definitive trial evidence is almost impossible and simply advise supplementation of the vitamin anyway, as it is associated with little or no risk. In medicine, particularly when seeing many patients daily, one learns to be pragmatic and develop a feeling for what intrinsically works. Indeed, several countries – but not the UK – fortify common foodstuffs with vitamin D on this basis. As you can imagine given our rather unpredictable weather, an extremely high proportion of people in this country are relatively vitamin D deficient.

It would be relatively straightforward for there to be a programme to try and boost vitamin D levels in those most at risk of severe Covid-19 infection and also to assist people in weight loss and smoking cessation programmes. Yet there has been virtually nothing from the NHS top brass on this. To compound this the main governmental strategy to combat coronavirus – lockdown – actually reduces our vitamin D levels, and by minimising exercise and increasing stress and boredom, our overall general health is made worse.

One has to guess as to why there is such an approach of seemingly ignoring the wider physical wellbeing of people by those who are leading the response to the virus. The question, unfortunately in my opinion, has not been asked of those responsible as the debate on health policy really has never got beyond the superficial.

It is very difficult for medically untrained correspondents to question scientists on fine details such as this and when there is any attempt to do so, it is too easy for the experts to give an answer which is beyond the expertise of the journalist to then challenge. The result of this has been a perception that the medical advice given is definitive. This can be problematic as the way we learn and improve our ability to care for people with disease is by constant reflection, analysis and critical appraisal of the evidence before us – otherwise one does not learn.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in