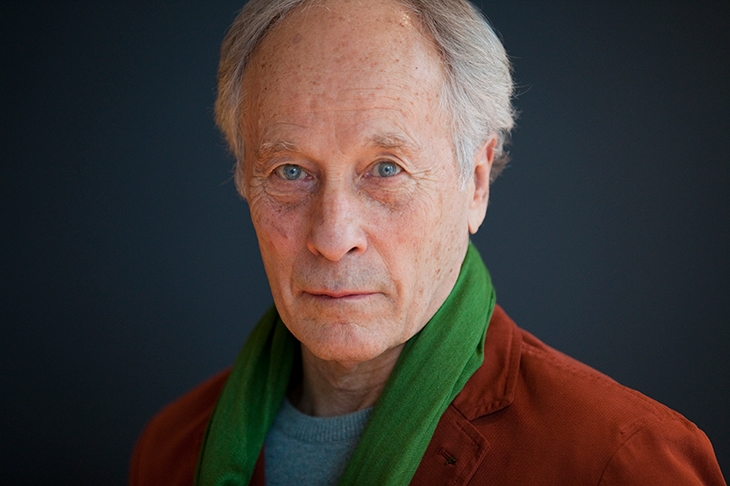

Sorry For Your Trouble (Bloomsbury, £16.99), Richard Ford’s 13th book of fiction, shows a writer still very much on song. The mainly male middle-aged protagonists of these nine stories seem often to be assessing their regrets but coming to terms with them. In ‘Second Language’, a man is enchanted by his glamorous second wife but able to accept when, after two years, she tells him (for no clear reason) that the marriage is over. Alongside multiple divorces, there are plenty of sudden deaths here — not least

that of a wife who simply lays her head on her hands and stops breathing. A doctor later diagnoses cancer, but the conclusion is: ‘Dying was likely the only real symptom she’d experienced.’

The most disturbing story is ‘Displaced’, in which a vulnerable boy becomes desperate for friendship after the death of his father. His only mate is a jaded, older adolescent who, unprompted, kisses him when they go to a drive-in movie. The friend concludes the evening by saying: ‘You’ll kill and steal and break people’s hearts and fuck your sister and burn down houses.’

The American protagonist of ‘Jimmy Green — 1992’ finds himself divorced and displaced in Paris on the night that Bill Clinton is elected. He is beaten up outside a bar after the result is announced, but simply returns home with his date, and at her request, walks her dog while she showers.

In ‘Crossing’, an American lawyer is on a ferry to Dublin the day he is getting divorced. He reflects:

Last night, having gone to sleep thinking of the journey today, he’d had the ridiculous sensation — not quite a dream — that the entire passage of life, years and years, is only actually lived in the last seconds before death slams the door. All life’s experience just a faulty perception. A lie, if you like. Not actual. At the end, though, to feel this way was freeing.

These accounts of mostly monied lives are written with conviction. In ‘Leaving for Kenosha’, a man attempts to buy a greetings card in Walmart on behalf of his 12-year-old daughter while she’s at the dentist, and is overwhelmed by the ordeal: ‘This task was past his capabilities, Hobbes realised.’

But if Ford’s protagonists are generally accepting, those in A.L. Kennedy’s We Are Attempting to Survive Our Time (Cape, £16.99) rage against their circumstances. In ‘Panic Attack’, a woman’s body betrays the symptoms of distress:

In certain moments a presence, a vile presence, might be holding her by the waist and tugging, tugging, rattling her, making her teeth meet in her head. It is forcing her to survive it.

Many of these stories are devastating, particularly ‘Point for Lost Children’, in which a homeless woman asserts: ‘They throw you away with nothing and say you’re fit for work and they don’t understand how much you want them to be right.’

If they offer scant comfort, Maria Reva’s are even darker, in Good Citizens Need Not Fear (Virago, £14.99), at times recalling Lyudmila Petrushevskaya’s short stories (one of which was entitled ‘There Once Lived a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, And He Hanged Himself’). These tales are not quite as macabre, but they are all set in a Soviet-era Ukrainian apartment block that has somehow been omitted from municipal records, along with its residents, who find different ways to survive. The most vivid is Zaya, a cleft-lipped orphan, who features in several stories: first in ‘Little Rabbit’, again in ‘Miss USSR’ (where she crashes a beauty contest) and later still as a sadist for hire in ‘Homecoming’.

Plotlines can be bewilderingly surreal; but there are also memorable flashes of description, particularly at the beauty pageant:

A heavily made-up teenager in a white slip, undoubtedly one of the contestants, limped in circles, sobbing. Another girl, hair set in pink rollers, was dry-heaving over a dustbin.

Margaret Atwood describes these stories as ‘bright, funny, satirical’, whereas I found them too often muddy and confusing. In ‘Novostroïka’, for example, to emphasise how often potatoes are used to replace unavailable ingredients in a canning factory, the word ‘potatoes’ is repeated for almost a page — with such deadening effect that it obliterates the entire point Reva is making.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in