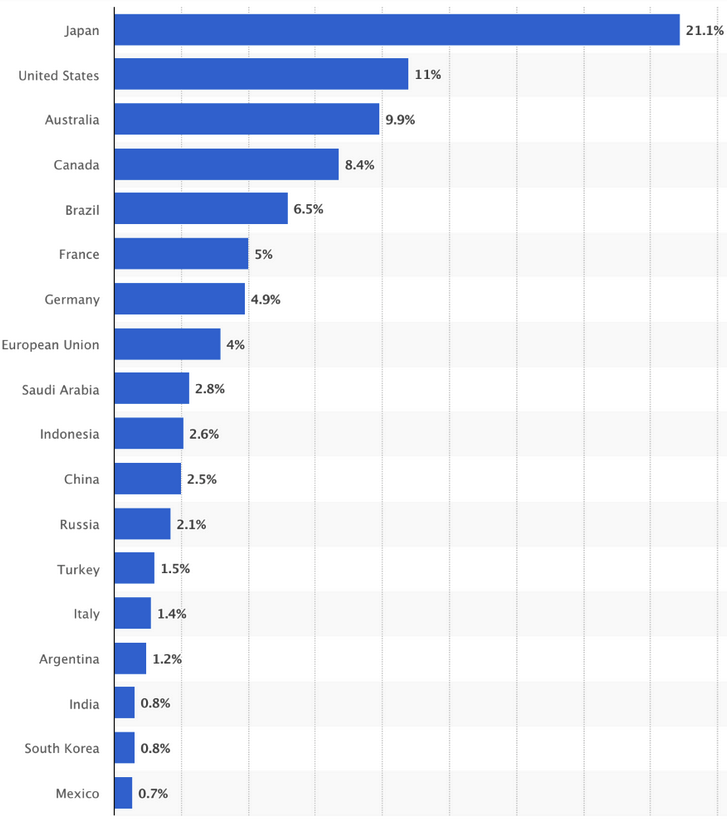

Relative to GDP Australian government spending to address COVID-19 has been among the highest in the world.

The Morrison government seems pleased to have been a world leader in mortgaging the future to combat the crisis. Its package, totalling $320 billion, comprises five elements:

- The PM’s initially announced health spending $2.4 billion

- JobKeeper and JobSeeker business support $168.78 billion

- Credit support$125 billion

- Access to superannuation$0.876 billion

- Income support$23.839 billion

The first two of these are supportive responses, though over-generous compared with those overseas. The third is similar but would be expected to be repaid at little cost should a smooth recovery eventuate.

Access to superannuation is simply permitting people to have some of their own money early (though might be regarded as a cost in so far as the absence of these forced savings would increase future pension payments).

Income support can be regarded only as a costly and counterproductive means of stimulating demand when the absence of this is not relevant. Enforced isolation means lower levels of spending (and the goods and services that are available for such spending are not undergoing any demand shortfalls). It is an item that for the Keynesian economists running Treasury is unashamedly a stimulus – and one that pushes on a string. For the politicians, it is a feel-good down payment for votes at the next election.

Even if the total package cost turns out to be as low as $200 billion, this raises national debt by 40 per cent. In addition, there is the loss of revenue from the much-reduced taxes that nearly half the workforce will be paying. The $220 billion that individuals pay in income tax if the crisis lasts six months is likely to mean over $50 billion less personal income tax

At issue is how to repay the expenditure, for unless one subscribes to the magical Modern Monetary theory, where spending is financed by borrowings from the central bank, spending cannot be costless. The alternative means of financing the expanded debt are to pay it gradually from future incomes or to raise the funds now and in the near future by taxation, other spending reductions or reducing regulatory restraints that suppress incomes.

One immediate revenue source is a temporary income tax surcharge on those unaffected by the measures. Out of Australia’s 13 million employed in March 2020, the Prime Minister has said that there are now six million people on JobSeeker and JobKeeper.

Broadly speaking, this means that these six million are earning, with the government top-up, 30 per cent less than they did.

None of the public sector’s two million employees are affected. Hence, those now earning at least 30 per cent less than they did comprise half of the 11 million people employed in the private sector.

As a result of the measures the government has taken, if the crisis effects last six months half of private sector workers are likely to earn perhaps 15 per cent less than expected. The costs to revenue are likely to be $168 billion plus and a further $60 million plus in reduced income taxes.

Ordinarily, there would be calls to have the burden shared, perhaps through a tax surcharge on those the government has not forced into unemployment. A 20 per cent tax surcharge on those still earning their full wage would raise around $40 billion. But the fact is those quarantined from the costs are the very ones – public servants and politicians – that are forging the policies.

Australia has such fabulous natural resources and has been so poorly governed over the past 20 years that there are multitudinous other government measures where reform can yield benefits. The $90 billion submarine folly and the $5 billion plus that is the Snowy 2 white elephant immediately come to mind. In addition, we could dismantle many other regulatory measures ranging from siphoning off Murray Darling irrigation water for spurious environmental uses through the regulatory barriers to mining developments and the billions of dollars wasted on subsidising renewable energy.

Will any of this take place? Probably not much because our politicians and their Treasury advisers are closet believers in Modern Monetary Theory Magic or at least prefer to put off the day when they rectify the national accounts. That outcome will leave us with a stagnant economy and one that may become wracked with inflation.

Alan Moran is with Regulation Economics. His latest book is Climate Change: Treaties and Policies in the Trump Era.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in