It is 178 years since the last recorded charge of blasphemy in Scotland, against the Edinburgh bookseller Thomas Paterson for ‘exhibiting placards of a profane nature’ in his shop window in 1842.

One of those placards announced that ‘Paterson & Co (of the Blasphemy Depot, London)… Beg to acquaint infidels in general and Christians in particular that… [we] will sell all kinds of printed works which are calculated to enlighten, without corrupting — to bring into contempt the demoralising trash our priests palm upon the credulous as divine revelation — and to expose the absurdity of, as well as the horrible effects springing from, the debasing god-idea.’ For good measure he added: ‘The Bible and other obscene works not sold at this shop.’ Richard Dawkins couldn’t have stuck it to Christians more pungently.

Anyway, Mr Paterson, a veteran of the English blasphemy wars, wanted a fight, and he got one. But interesting as his fate is, it’s not what you could call a current grievance. Which hasn’t stopped the Scottish government from proposing to do away with the blasphemy law, modernising it and extending it to cover discrimination against age, disability, race, religion and sexual orientation.

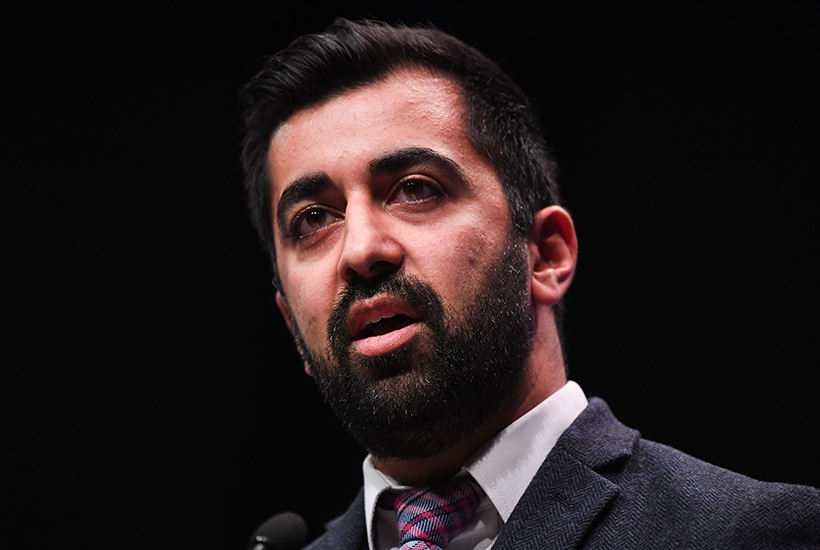

The Scottish Justice Minister Humza Yousaf said: ‘Stirring up of hatred can contribute to a social atmosphere in which discrimination is accepted as normal. By creating robust laws for the justice system, parliament will send a strong message to victims, perpetrators, communities and to wider society that offences motivated by prejudice will be treated seriously and will not be tolerated.’

Trouble is, offences motivated by prejudice lack the relative specificity of the old blasphemy law, which aimed originally to prevent the vilification of the Christian religion, and later, to prevent breaches of the peace caused by unbelievers outraging religious sensibilities in a wilfully provocative way. The offence of blasphemy in its later form wasn’t intended to defend God as such — in England, a 1917 case involving the Secular Society expressed the principle that God could look after himself — deorum injuriae diis curae. The law was meant to ensure that anti-God rhetoric wasn’t wilfully provocative. Insults could be visual: in 1909 an exhibitionist was accused of blasphemy in Dublin after appearing at a public skating rink dressed ‘as a travesty of Christ’.

The rule of thumb when it came to deciding whose religious feelings should be protected was that the law should defend those of reasonable people and the general community, not nutters.

The offence of blasphemy was abolished in England in 2008. Irish blasphemy laws were removed by referendum after there was the horrible possibility that they could be used against Stephen Fry, who had opined on Irish television that ‘the God who created this universe, if it was created by God, is quite clearly a maniac, an utter maniac, totally selfish’. If he’d said something about the incompatibility of divine omnipotence and the existence of evil, no problem.

The reality, not just in Scotland, is that replacing blasphemy laws with hate legislation acknowledges that this society has its notion of the sacred, of protected ideas, just like previous generations did. They’re just the polar opposite of the old Christian ones. And whatever about the legal penalties, their violation often entails a persecution that’s more pervasive than the old sort.

Do I need to spell out what the new orthodoxies are? Mr Yousaf’s proposals suggest the outlines of the new no-go areas. How about these positions? That gender is not a social construct but a biological genetic reality. Taking issue with aspects of Islam relating to the life of the prophet of Islam. Expressing the view that abortion is immoral because it involves taking a human life (it’s forbidden to demonstrate outside clinics in many cities). Suggesting that the best model of parenthood is the heterosexual married couple. Pointing out that a man accused of predatory sexual behaviour isn’t guilty simply because women say so. Refusing to accept that all alleged victims of abuse must be believed, regardless of the evidence.

If the Scottish government does replace the old blasphemy law, perhaps they should consider keeping the word blasphemy in there somewhere. That way, we’d know what we were doing in challenging the consensus. We’d be subverting the new orthodoxies, outraging public feeling.

Except the new orthodoxies don’t need legal protection. The punishments of ostracism, no-platforming, Twitter lynching, deselection by political parties (Robert Flello, former Labour MP, was deselected by the Lib Dems as their candidate for Stoke-on-Trent South in 2019 for being off-message on gay marriage), petitioning for dismissal (students tried to get the philosopher John Finnis sacked from Oxford for his views on homosexuality) are more various than the old ones and don’t actually need the sanctions of a court.

The spirited unbeliever Thomas Paterson conducted his own defence in his blasphemy case. He observed: ‘In any really well-governed realm, so far from attempts being made to bludgeon men into silence, if they dared to speak heterodoxy, measures would be taken to encourage the free and honest expression of opinion, for the inevitable effect of coercing thinkers into a seeming acquiescence with creeds, fashionable or established, is a plentiful crop of hate, disgust and hypocrisy.’

We’ve got established and fashionable creeds now all right, with nonconformity called out and sanctioned. Mr P would, I think, be a little depressed at the outcome.

While we’re about it, we could give some thought to a country where the blasphemy laws really matter, viz, Pakistan. Christians, who constitute around 2 per cent of the population, are ten times as likely as other citizens to be charged with blasphemy. The law is a means to hold minorities, including non-conformist Muslims, in a state of perpetual fear lest they inadvertently offend against Islam — the case of Asia Bibi is only the best known. You might think that the British government would take this into account in its dealings with Imran Khan, the prime minister formerly much in demand in the best London society. The blasphemy laws aren’t amusingly archaic in Pakistan; they’re a matter of life and death.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in