Save the children

Sir: Your leading article is correct that the government should have evaluated the detriment caused by shutting schools, against the risk posed by Covid-19 (‘Class divide’, 16 May). This is not a glib trade-off between protecting lives and allowing children to go to school: the predicament foisted on young people will affect their future for decades.

Exams were abruptly cancelled in March. This has left many schools dealing with apathetic individuals. The disparity between disadvantaged and affluent students is widening: middle-class schoolchildren are twice as likely to receive online tuition, and only 8 per cent of teachers in low-income communities report more than three-quarters of work being submitted, compared with 50 per cent in the private sector. The government claims to be ‘following the science’. But it seems that the effect school closures have on curbing the virus is tenuous. If the government explained this, more parents would want to send their children back.

Schools and colleges should reopen for all pupils on 1 June. Given the inordinate harm being inflicted on poorer children, time cannot be wasted.

James Smith

London SE9

On accepting risk

Sir: As a teacher in a comprehensive state school, I and most of my colleagues have no opinion on the opening of schools from an epidemiological perspective. But many of us do want a strong case to be made for the value of schooling alongside the warnings of the health risks taken by returning students to their classrooms. We are proud to serve our communities and we hope that what we do is important enough that accepting some risk to health is worth it. Thank you for making this argument.

Graham Marsh

Cambridge

Heights without depth

Sir: I feel even Hitchcock himself may have agreed with much of Deborah Ross’s assessment of Vertigo (The Heckler, 16 May). The director famously considered his films less slices of life than ‘slices of cake’. It was only pretentious French film critics of the 1950s who assigned any level of depth to the Hitchcockian oeuvre. Modern critics have lazily inherited this interpretation. It’s about time we restored the great man’s reputation as a master of suspense who occasionally turned out garish, clumsily plotted nonsense like the movie currently being touted as the greatest ever made.

Matt Pitt

Brighton

Full circle on Dizzy

Sir: As always, Alistair Lexden displays learning and lucidity (Letters, 16 May). He is right to extol Robert Blake’s Disraeli; there is no more enjoyable political biography in the language. Even so, when Lords Blake and Lexden claim that Dizzy was more than a ‘lucky charlatan’, they are defying the evidence. Solely motivated by ambition, Disraeli broke up the Peel government, split his party and ensured that it would be 28 years before it could form a majority government. Nearly 180 years later, it is still possible to be angry with Peel. Goaded beyond endurance by Disraeli, he asked him why, if he found his leadership so distasteful, he had asked to serve under him. Disraeli denied having done so. Had Peel produced the letter — which survived — Disraeli would have been destroyed. Lord George Bentinck might well have horse-whipped him on the steps of the Commons. He would instantly have become an unlucky charlatan. Yet there is one argument to be made in Dizzy’s favour. In 1867, over the Second Reform Bill, he deceived his colleagues, invented figures and revelled in a serene contempt for truth. But this charlatanry may have been in his party’s best interests. Did Disraeli foresee the inexorable march towards democracy? Was he determined to ensure that the Tories did not find themselves on the wrong side of history, as they were in 1832 over the Great Reform Bill (before being rescued by Peel)? Or did he merely want to dish the Whigs and cling to office? We shall never know.

Bruce Anderson

London SW1

Scruton the seeker

Sir: May I be allowed a comment on Sue Prideaux’s judgment that ‘Scruton didn’t believe in God’ (Books, 9 May)? I knew Roger for 35 years. He preached for my congregation when I was Rector of St Michael’s, Cornhill. Over those years, Roger spoke to me at length and, as you might imagine, in depth, about the deep matters of faith. From these conversations, I can lustily affirm that Roger was no atheist: he did not not believe in God. He was always seeking to satisfy his mind on this subject: always, as he himself would put it, ‘on the lookout’.

The Revd Dr Peter Mullen

Eastbourne, East Sussex

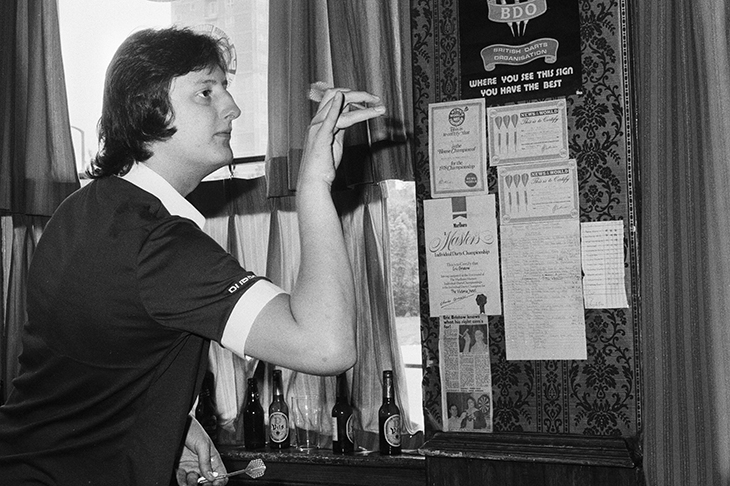

A sport and a game

Sir: I am a work colleague of Rory Sutherland. So I correct with hesitation his ranking of sports (The Wiki Man, 9 May). My understanding was that if you could drink during a recreational activity, it’s a game. If not, it’s a sport.

Tommy MacDonnell

Dublin, Ireland

Following the Izal

Sir: In 1968 while serving in the army, my sister and I decided to drive to Switzerland to join a ski party. We did not have a map, but army friends lent us their AA map of Europe so that we could trace the route. We did not have any tracing paper — and time was short. Fortunately the British Army still used Izal (Letters, 9 May). So from Bulford Camp, Wiltshire, we traced our route over 23 sheets of Izal, across France to Verbier. It worked, and we made Verbier in good time.

Mark Brazier

Cheltenham, Gloucestershire

Write to us: letters@spectator.co.uk/>

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in