The Morrison government has flagged tax cuts and aggressive deregulation as part of a pro-business road to economic recovery. A focus on stimulating rapid growth on the other side of the coronavirus pandemic is expected to guide October’s federal budget. — AAP report, April 20.

Future government action must focus strongly upon savings as a result of the 15 per cent of GDP ($340 billion) that has been spent on combating coronavirus.

Fifty years ago, the Commonwealth budget accounted for 18.3% of GDP. In the years since then, even before the current spending spree, the share had grown to 24.6%. Right now, with an extra $340 billion budgeted, the share of GDP will have become 35 %.

The nation’s phenomenal intrinsic wealth allowed Australia to prosper in spite of the growing claim on income by a largely unproductive government sector and an even greater impost from expanding regulatory impositions and prohibitions placed on productive activity.

While most government spending is poor value, a great deal of it actually creates negative value – it destroys value in addition to the costs incurred in funding it and its associated paper burden. Mathias Corman among others has called for deregulation that has now become urgent to allow the economy to mend. Anthony Albanese, predictably, has slammed this as “right-wing ideology”.

Here are seven deadly sins that are candidates for immediate reform. Although some of these (urban planning, gas exploration, locking up land in national parks) are state responsibilities, as with the reform agendas in the 1990s, the payments from coronavirus grants offer the Commonwealth leverage to force the state government into productivity-enhancing reforms.

Industrial relations

Uniquely in the world, Australia has a system where wages and working conditions are set by an “independent” body dominated by former trade union leaders. The ALP, when in government, invariably seeks to expand this coverage into contractors and others it argues should be “deemed employees”.

As Steve Knott has shown, and as corroborated by the attempts to change arrangements in light of the COVID-19 crisis, the system’s 122 minimum standards are highly inflexible.

Setting mandatory wages and working conditions ostensibly favours employees over employers. But nobody can be sustainably paid more than they produce, except at the expense of others. Attempting to do so lowers national productivity. Employment flexibility requires the Fair Work Commission’s functions to be stripped back to become similar to those in other jurisdictions where they are limited to oversighting issues of unfair dismissal and human rights abuses.

Land use regulations for housing

While Australia’s apartment blocks are built under union tutelage and more expensive to construct than in other nations, the house building industry is based on sub-contracting and is among the lowest cost in the world.

But overriding the low-cost housing construction, vested interests combined with ideological aversion to “urban sprawl”, have created regulatory barriers to converting farmland to land for new houses. Publications like Demographia show that Australia’s system of urban planning has created among the most expensive houses in the world – a remarkable achievement for a nation that has the world’s most ample land supplies!

While in Germany and US cities like Houston, Atlanta, Cincinnati and Chicago, median house costs are around three times median incomes, those in Melbourne and Sydney are nine times median incomes. Other Australian cities are not far behind.

Planning regulations, in rationing the use of land for housing, especially on the city peripheries, mean that once an area is approved for housing, the uncleared land previously worth $15,000 per hectare becomes worth $1-2 million. The land component of a new house is thereby priced at upward of $200,000, compared with its worth in the absence of regulatory measures of just a few thousand dollars. Because of these regulations, a new four-bedroom house in places like Houston costs around $A250,000, three times that of its Sydney or Melbourne counterpart. These cost boosting measures are also reflected in the existing stock’s prices.

Reforms would eliminate measures that restrict the availability of and for housing.

Land use regulations: to prevent mining, agriculture and timber getting

To appease green agitators and to virtue signal, state governments have vastly expanded areas of declared national parks. Victoria has been especially prominent in pursuing this quarantining of land from commercial uses.

The current fire season has once again demonstrated that the creation of national parks (which in Australia, unlike in most other countries, means forbidding most commercial activity) brings limited permitted clearing and an absence of the heavy firefighting equipment that is present where logging takes place. The disastrous consequences have been identified by Roger Underwood.

The loss of land for mining, forestry and agriculture is even more costly. These costs were assessed for the Goldfields area, the latest slice of the state forests planned by the Victorian Government to be taken out of productive use. For the Goldfields region alone, the targeted area is close to a relatively recent gold mining development and would, if closed to commercial activity as the Government plans, bring costs to the people of Victoria over coming decades estimated at around $3 billion.

Reform would involve preventing further land use restrictions on public land and seeking to remove existing restrictions which have negative value.

Electricity reform and greenhouse policies

In a recent article, I showed the direct subsidies for renewable energy, at some $4 billion per year, had forced more reliable coal generators out of the market and lifted wholesale prices by $13 billion a year. Abandoning all subsidies for renewables would allow energy users to recoup the costs these impositions have brought to energy consumers, both household and commercial, and offer a major boost to firms’ competitiveness.

The subsidies are sold as being to meet the Government’s obligations from its accession to the 2016 Paris Agreement on Climate Change. They are among many other economically harmful measures in place in pursuit of these emission–defraying goals.

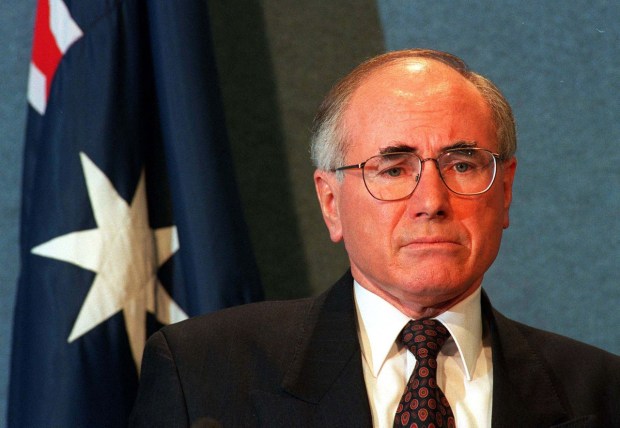

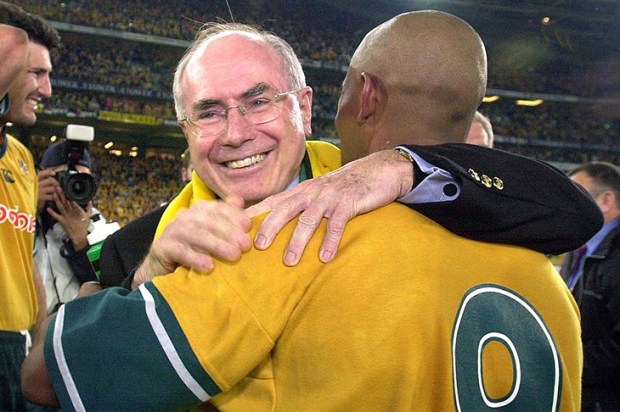

One of the most harmful of such other measures was implemented by the Howard Government in collusion with the ALP governments in NSW and Queensland. This prevented agricultural land clearing, without which Australia would not have achieved the emission reduction goals it set for the 1998 Kyoto Convention. The economy-wide costs in lowering the value of farmland were estimated at $200 billion. One notorious case was that of Peter Spencer where the Appeal Court judge refused compensation for the value the appellant lost from his land being reclassified on the grounds that “just terms” compensation was not provided for in the NSW constitution!

The reclassification of land to defray greenhouse gas emissions remains a policy goal of the ALP and the Greens. In order to ensure owners have the ability to improve their land, governments should be required to compensate them for regulatory costs.

Embargos on gas exploration and drilling

Aside from Queensland (and recently the Northern Territory) state governments have been spooked by a mix of green activists’ and farmers’ concerns into banning the use of fracking techniques to extract gas unconventionally. The fracking technology has been in place for over 60 years, is well proven and safe and has converted the US from being a huge net importer of oil and gas into a net exporter.

Similar results are available for Australia where, in response to the embargos, gas prices have until recently been three times those in the US. Mining engineer, Jeremy Barlow, covered the costs of present policies and potentialities for change.

States should be required to allow this process to be available to producers.

Restoring irrigator water in the Murray Darling

Among the most egregious policy developments in recent years has been the removal of around 20 per cent of the water formerly assigned to irrigators in the Murray Darling region responsible for 40 per cent of the nation’s agricultural output. As a result of the measures, water shortages (aggravated by drought) have brought a tenfold increase in the water price. This has led to the impoverishment of many farmers.

The water was needlessly taken to assuage green activism. It did nothing to enhance environmental outcomes. If sold back to farmers, this vital agriculture input would bring an increase in value of some $12 billion over the next 10 years.

The Great Barrier Reef

Walter Stark points out that public attention and concern generated by phoney claims that the GBR is threatened have become the foundation for an ongoing taxpayer-subsidised industry devoted to “saving the Reef” at a cost of several hundred million dollars per year.

This is another example of negative value expenditure – not only is the funding in search of a confected problem but it has brought about unnecessary costs to farmers on the Queensland mainland.

The accumulation of environmental regulations

The nine-year gestation period in the permitting of the Adani coal mine in Queensland stands in stark contrast to that which preceded the opening of the Kambalda nickel mine in Western Australia during the 1960s. From its discovery to commencing development Kambalda took just eight months, catapulting Western Mining to become one of Australia’s biggest mining houses.

One of the more important blockers among the layers of environmental regulations are the laws designed to combat the so-called species loss Australia faces. The Australian Environmental Foundation has demonstrated that the alleged loss is illusory. A vast bureaucracy has been created to police and continuously add to species nominated for protection – often in the confines of “unique ecological communities”. The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC) is at the heart of Commonwealth controls and an example of unnecessary and harmful expansion of responsibilities the Commonwealth has assumed over the past decades.

The Act covers an undue number of issues which duplicate state acts. Indeed, the opening objective, “provide for the protection of the environment, especially matters of national environmental significance”, makes this clear with the word “especially” pregnant with an unnecessary Commonwealth trespass on State responsibilities.

Among the totally irrelevant provisions are those covering the EPBC

- nuclear actions (including uranium mining)

- a water resource, in relation to coal seam gas development and large coal mining development.

Uranium mining should be treated like any other mining as a matter for state responsibility.

The provisions on coal mining and CSG appear to have been inserted in deference to particular matters that are the target of powerful pressure groups and should not be incorporated in general national legislation.

Environmental regulations have grown relentlessly and must be cut back.

Alan Moran is with Regulation Economics. His latest book is Climate Change: Treaties and Policies in the Trump Era.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.