The situation in Spain due to coronavirus is dire. But what is particularly horrifying, is how many of the nation’s elderly are being neglected during this time. BioEdge reports that:

Not all of the human drama in the Covid-19 pandemic is cheeriness under pressure, heroic doctors and nurses, and the generosity of neighbours. Some very bad stuff can – and probably will – happen.

Nothing illustrates this more vividly than what happened in Spain this week. On Monday, military units seconded to help in the crisis entered various residential centres for seniors in Madrid. What they found was appalling. Some of the residents were dead in their beds. Others were wandering around “in a state of complete abandonment” with poor hygiene. It sounds like a canto in Dante’s Inferno.

And worst of all, the care workers were nowhere to be seen. They appear to have fled, terrified of contracting the coronavirus.

For these residents, it must have been the worst death imaginable – alone, helpless, choking, without any accompaniment in their last moments.

Even more shocking, according to the English translation of the Spanish newspaper El Pais:

Many seniors have fallen ill in care homes without ambulances taking them to hospitals. Some family members have said that their parents or grandparents are being left to die because they are considered lost causes, as they have prior medical conditions or are of an advanced age. One worker said they had been looking for someone to help a 91-year-old man who was struggling to breathe since early Thursday morning. Last Friday, a doctor visited him and said he was a “possible Covid-19” case but did not have a kit to confirm the diagnosis.

“I see this man crying and he should be cared for in a hospital,” said the worker, who asked to remain anonymous to protect their job. “We have called 112 [for emergency services] seven times and nothing. After waiting two hours, they told me in an unfriendly tone that they couldn’t help us.”

If there is any “positive” to come out of this unmitigated disaster, maybe it’s that people will reassess their view of euthanasia. For as we are seeing, it is the elderly who are most vulnerable in relation to coronavirus. Note that of coronavirus deaths in Australia, The Guardian reports that the youngest fatality was a sixty-eight-year-old man.

As the experience in Spain shows, there need to be legal protections for people in tragic situations such as these. Dr Hannah Graham (Lecturer in Criminology at the University of Sterling) and Dr Jeremy Prichard (Associate Professor at the University of Tasmania) have produced a comprehensive report outlining the plethora of reasons as to why legalising euthanasia is so problematic.

First, is the obvious potential for elder abuse. The European Court of Human Rights has stated, “The risk of abuse inherent in a system which facilitated assisted suicide should not be underestimated.” As Dr Pritchard has stated in The Examiner:

In coming decades we face a rapidly aging population, a shrinking tax base and increases in health problems like dementia…euthanasia could form part of government planning for service provision for people nearing end-of-life…If that sounds far-fetched, consider two cases from Oregon where patients’ applications for medical treatment were rejected, but followed by departmental notifications informing the patients they were eligible for assisted dying.

Second, the bioethical. At the heart of this issue is the role of the medical professional. In particular, are they a healer, helper or killer? Significantly, a national survey in the United Kingdom has shown that the majority of doctors do not support the practice of euthanasia. What’s more, our own Australian Medical Association has also been highly critical of the practice. Dr Christopher Middleton has stated:

I think it would completely change the mind-set and the ethos of medicine in Australia because in their practice, in training, doctors tend to see themselves as agents of hope and healing and comfort, and certainly not as agents of death.

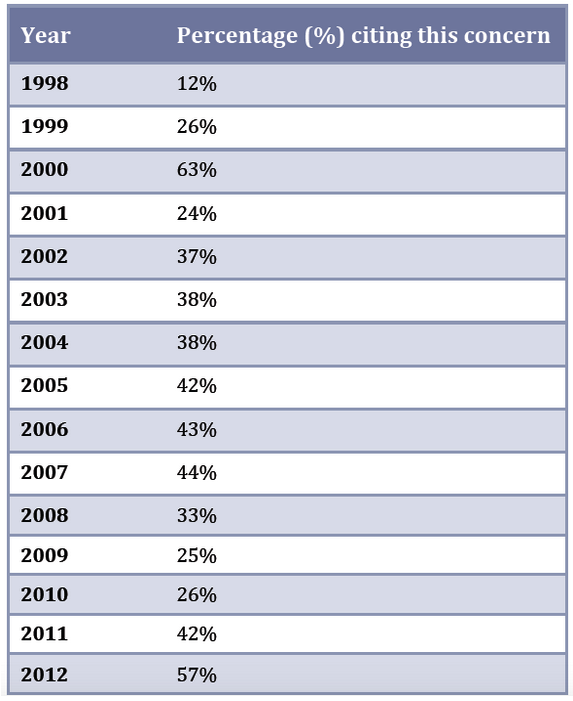

Third, the psychological pressure to end one’s life. Note the following table based on statistics from Oregon, which shows that since euthanasia has been made legal there has been a significant and steady increase in people choosing euthanasia so as not to be a burden on their family and friends.

Fourth, is the negative societal perception of those who have a disability with their deaths being treated as an act of ‘compassion.’ Graham and Pritchard state that, “The implication that some people are ‘better off dead’ and that ‘some lives are not worth living’, phrases which have been used internationally in euthanasia debates, are potentially offensive and stigmatising to those who live with the same or similar symptoms and conditions.”

Fifth, is “bracket creep.” What has been observed in countries that have legalised euthanasia is that the wishes of family members have pressured the patient to choose to be euthanised. What’s more, there is widespread under-reporting of the practice and there has also been a significant increase in the use of ‘terminal sedation’ resulting in the patient’s death. For instance, Dr Philip Nitschke, one of the leading proponents for legalising euthanasia, has been quoted as saying:

In the intervening 16 years since the Northern Territory Rights of the Terminally Ill Act came and went, the debate on voluntary euthanasia has been extended beyond those who are terminally ill, to include the well elderly (sic) for whom rational suicide is one of the many end of life options.

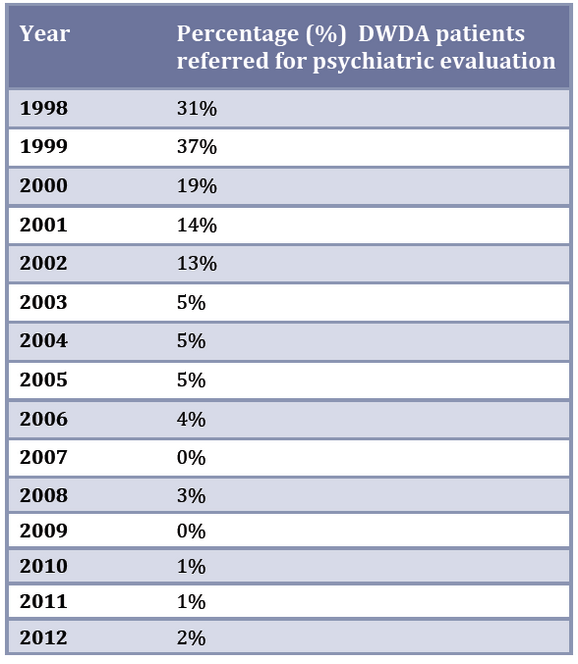

Sixth, the ‘safeguards’ of psychiatric referral and assessment are gradually ignored. Graham and Prichard state that, “In the Flanders region of Belgium approximately half of euthanasia cases are not formally monitored as doctors do not report them to authorities. The rate of underreporting in the Netherlands appears to be between 20-23 per cent.” What’s more, in Oregon, the percentage of people being referred for psychiatric evaluation has dramatically decreased, as can be seen in the following table:

Seventh, is the eventual practice and acceptance of non-voluntary euthanasia. In Belgium, where euthanasia has been legal since 2002, it has been observed that people were put to death without their consent. What’s more, nurses have taken upon themselves, without the presence of a doctor, the responsibility of administering euthanasia drugs.

Eighth, numerous countries have examined and rejected it. No country should feel that they are on the “wrong side of history” in rejecting this practice when the majority of countries around the world have decided against its legalisation.

Ninth, is the associated guilt that occurs when a medical professional is involved in ending another person’s life. For instance, Dr Kenneth Stevens, after researching this particular aspect, makes the following finding:

The physician is centrally involved in PAS and euthanasia, and the emotional and psychological effects on the participating physician can be substantial. The shift away from the fundamental values of medicine to heal and promote human wholeness can have significant effects on many participating physicians. Doctors describe being profoundly adversely affected, being shocked by the suddenness of the death, being caught up in the patient’s drive for assisted suicide, having a sense of powerlessness, and feeling isolated. There is evidence of pressure on and intimidation of doctors by some patients to assist in suicide. The effect of countertransference in the doctor-patient relationship may influence physician involvement in PAS and euthanasia.

Tenth, there are gendered risks, especially for women. There is a growing body of academic literature that highlights the ‘disproportionate victimisation of women’. As Prichard and Graham explain:

It is vitally necessary to carefully consider the potential for gendered violence and familial control to be directly or subtly influential, if not implicated, in matters of the ‘voluntary’ assisted death of women. Where there has been coercion, control and gendered violence in a woman’s life, the nature of which may often be kept hidden and secret from others (including in professional and personal relationships) in her life, it is important to ask whether this might be a factor in a woman’s death.

In Newspeak that would have made even Orwell gasp in disbelief, the term ‘euthanasia’ has been given a plethora of innocuous-sounding alternatives; ‘Voluntary assisted dying,’ ‘dying with dignity’, ‘therapeutic homicide’, ‘therapeutic killing’, ‘mercy killing’, and ‘physician-assisted suicide’. However, there is never such thing as a “good death,” as the word ‘euthanasia’ would etymologically have us believe.

The recent events that have occurred in Spain are a prescient warning as to some of the dangers that lie ahead in adopting it. Of course, it’s not what people envisage “dying with dignity” with be like. But it’s a horrific example as to what many people rightly fear will ultimately take place if legal safeguards are removed.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Mark Powell is the Associate Pastor of Cornerstone Presbyterian Church, Strathfield.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in