Red tape is exacerbating the economic fallout brought on by the coronavirus crisis by making it more difficult for businesses to adjust to changing circumstances.

While no one could foresee the outbreak of a global pandemic, politicians and bureaucrats have willingly ignored the red tape crisis for years.

Red tape increases the likelihood of economic crises, deepens these crises when they occur, and prevents a quick economic recovery.

Red tape makes the economy more susceptible to economic shocks by putting unnecessary pressure on businesses even during the good times. Many businesses, especially small and family-owned ones, run on very slim margins which are made even slimmer by unnecessary compliance obligations. When a crisis hits and cash flow slows, red tape diverts resources away from recovery and toward compliance.

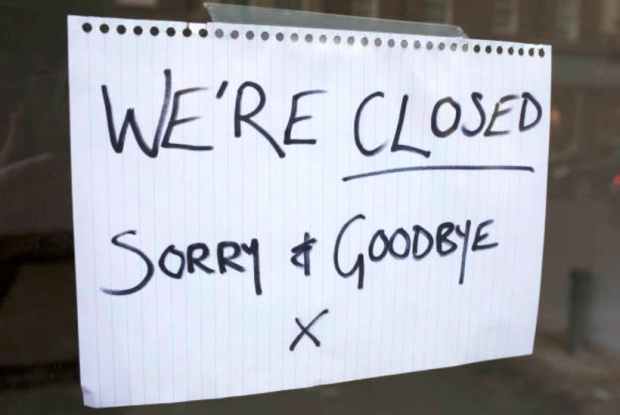

During a crisis red tape prevents businesses from responding in the most effective way. Rather than adapting their business model or innovating to respond to the changing needs of consumers, some businesses are left with no choice but to shut down. This creates enormous stress for owners, with many small business owners risking their family home used as collateral for business loans, and for employees who are now out of the job.

And red tape acts as a handbrake on economic recovery by adding to the cost of starting new businesses and employing new staff.

Three recent examples demonstrate how red tape is making the current economic crisis worse.

Food truck owners in Western Australia have warned that they are likely to lose their livelihoods as their entire calendars are cancelled in order to comply with the federal government’s limit on the size of gatherings. To respond, food truck owners want the freedom to serve food in alternative settings. Cafes and restaurants have been allowed to respond to the lock-downs announced over the weekend by providing takeaway or delivery options. Excessive compliance obligations, however, prevent food trucks from adapting in a similar manner.

Food trucks must be registered under the WA Food Act 2008, with the council where the truck is stored, and with each council they wish to operate in. Each of these registrations requires submitting a form (usually around five pages long), providing supporting documents such as a floor plan and evidence of the truck’s registration with the council it is garaged in, and paying a fee. These forms typically take around 10 days each to process and once approved food trucks can only be operated in specified areas of each council.

Sandra Bahbah, who owns a Perth-based food truck, explained to WAToday, “This is going to be a disaster for the industry. A lot of [businesses] will fail because they won’t be able to afford the hit”.

Supermarket operators want to respond to rapidly escalating demand by restocking outside of the usual hours so that the shelves can be full for customers the following day. But rules which prohibit supermarkets from making deliveries outside of strict timeframes prevent this stocking from occurring. These timeframes vary from council to council, and between different supermarkets within each council. Russell Zimmerman, executive director of the Australian Retailers Association, explained the situation to The Australian earlier this month, saying “If we could get those trucks into those retail stores at other times beyond the curfew times [typically 7am to 10pm], there is a huge opportunity to get the stocks into the shelves so that people would then realise that the stock is there”. Fortunately, some states have acted on this, but there is much more to do.

Section 487 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 allows activists to engage in ‘lawfare’ to delay and disrupt major development projects. Recent research from the Institute of Public Affairs estimated that this has put $65 billion of investment at risk since the year 2000 by holding up projects in court for a cumulative 10,100 days. Section 487 has placed a significant burden on the economy, but it does not improve environmental outcomes. The IPA has demonstrated that 94 per cent of cases brought about through it have not resulted in substantial changes to the original project proposal.

These three examples illustrate the broader cost of red tape which the Institute of Public Affairs has estimated to be $176 billion each year. This cost captures of all the businesses never started, the pay rises never given, and the hours spent complying with the edicts of unelected bureaucrats rather than training new employees and running a successful business.

This red tape burden is one of the key causes of Australia’s weak economic foundations. New private sector business investment is only 10.9 per cent of GDP. This is the lowest level since the last recession in 1990-91 and is even lower than the average rate in the turbulent times under the Whitlam government.

Low business investment is caused by excessive red tape, an inflexible labour market, and a corporate tax rate that towers above the OECD average.

No matter how quickly or slowly the coronavirus crisis passes, these structural issues must be addressed.

Governments at the local, state, and commonwealth level must cut red tape to lessen the severity of the forthcoming economic crisis, and enable a quicker recovery where businesses can open and people can get back into work.

Cian Hussey is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Public Affairs. Join as a member at www.ipa.org.au.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in