Plague and pestilence have always ushered in social and economic dislocation. The Antonine Plague of the second century AD marked a turning point in the fortunes of the Roman Empire. The Black Death caused widespread economic and social disruption, and even a return to serfdom in Europe. The Great Plague of London in the seventeenth century had similar far-reaching consequences.

So, will the COVID-19 pandemic be any different?

The Black Death in Britain and Europe is the first pandemic for which we have reliable data on the economic and social consequences that accompany widespread disease. In scenes similar to today, shopkeepers closed their doors, people attempted to flee cities for the country, and strict quarantine measures were put in place

In Britain, the large scale loss of life precipitated a shift from cultivation to animal husbandry, which would ultimately lead to widespread land enclosure. Reading through extensive histories from the period however, it is obvious that some families did very well, while others suffered massively.

The determinant of whether people emerged richer or poorer after the Black Death was their circumstance before the outbreak began. Those who thrived were the ones who had sufficient savings or income to embrace the opportunities which presented themselves. But those who suffered were those who were in debt, including the aristocracy.

Fast forward to 2020, and the same will be the case again. The people who will suffer most are those who lose their jobs and are heavily indebted, however in debt-laden Australia, that will be many.

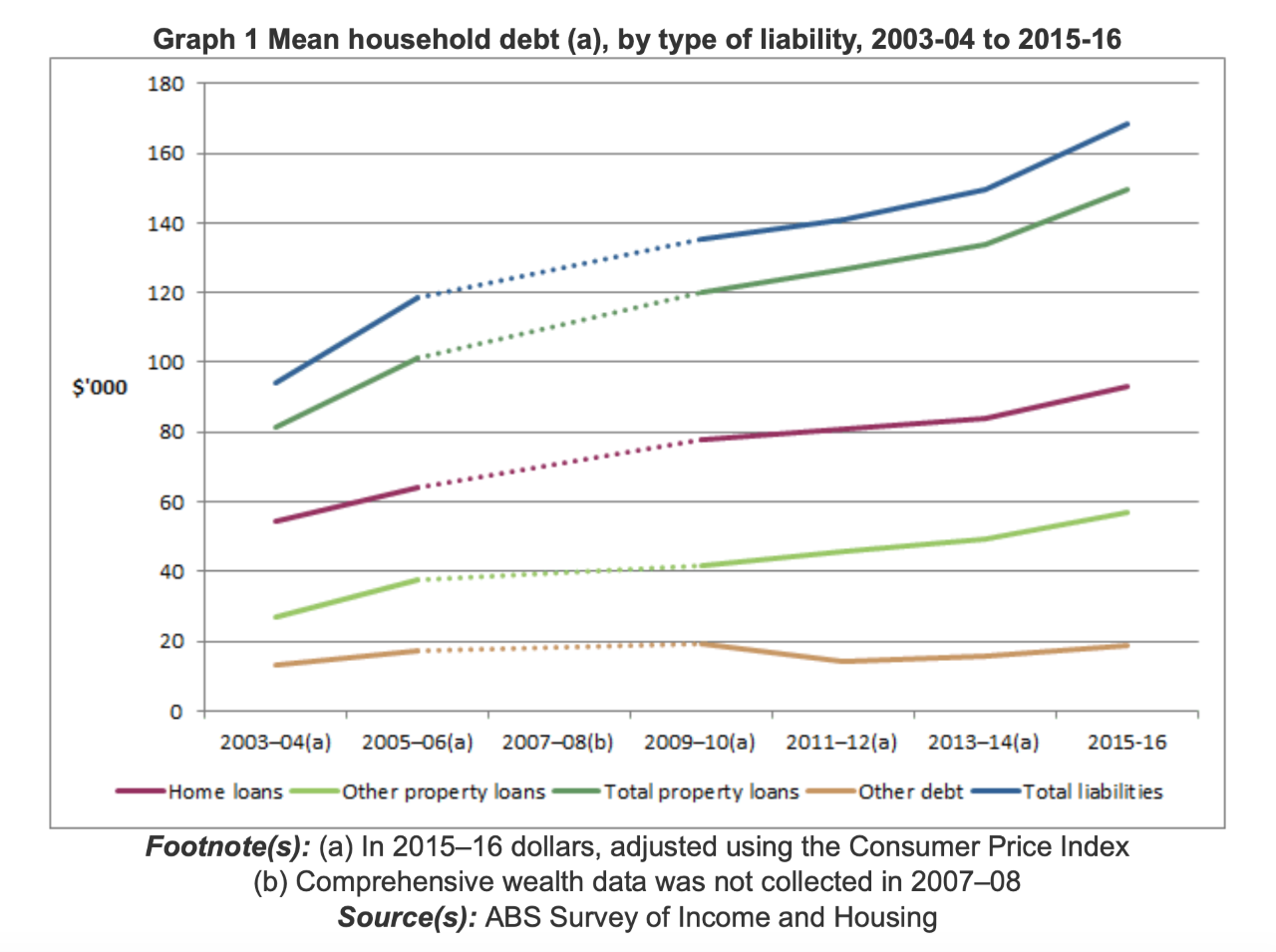

The ABS Survey of Income and Wealth 2015-16 released in 2018, contained a number of sobering observations on household debt in the Australian economy.

The ABS Survey of Income and Wealth 2015-16 released in 2018, contained a number of sobering observations on household debt in the Australian economy.

In fairly blunt terms, the ABS noted:

High levels of debt, when considered against the value of current household income and assets, indicates vulnerability in the event of an economic shock, such as increases to interest rates, the loss of a job, illness or injury, a change in family circumstances or a drop in asset prices.

That economic shock is here now, and Australia is horribly exposed.

Between 2003-04 and 2015-16, mean household debt increased by 79 per cent, but mean asset value increased by 51 per cent and gross income by only 38 per cent.

Disturbingly, much of that increase in debt occurred after the Global Financial Crisis. Moreover, that increase in debt was driven by the Reserve Bank cutting interest rates to facilitate further borrowings.

Put simply, Australia’s response to the debt-driven GFC has been to grow more and more debt — at a rate that far outpaced the growth in income.

This was supposedly in pursuit of the RBA’s growth objective. The additional debt was supposed to encourage additional growth in the economy.

There are many problems with such a strategy. The most salient is that ever-declining rates of interest that have been necessary to encourage Australians to borrow. If more debt had grown the economy sufficiently, it would not have been necessary to continue cutting interest rates. The downward slide in interest rates is proof of the failure of the policy itself.

As the ABS points out, the percentage of households which are over-indebted rose from 21 per cent to 29 per cent in the twelve years to 2015-16.

If ten per cent of the workforce lose their jobs, then what will it do to home prices, and the facade of wealth that they represent?

The solution, I predict is that the banks will offer to capitalise people’s unpaid home loan interest on condition that the Government guarantees the liabilities. That will suit the banks perfectly – capitalised interest and rescheduled loans mean people paying the banks more interest and for longer.

Government will agree to this because no government since 2008 has had the courage to call out Australia’s massive debt farce, for fear house prices will fall and the people will turf them out of office. The problem is that would give the banks risk-free loans with a residential mortgage spread. It’s nice money if you can get it.

The end result will be to burden some with crippling debt they will never repay. These are the zombie borrowers. They will still be walking, but economically dead with debt.

And lest we think stimulus packages will save the day, we should remember they too are built on debt. Net Commonwealth debt stood at $361 billion at the start of the pandemic, but $189 billion has already been added to that in the initial rounds of stimulus packages. That debt will have to be repaid, and that will come in the form of higher taxes.

This is not the end of the story. It is not even the beginning of the end of the story; it is but the beginning.

Illustration: Idiot Box Productions/Circle of Confusion/Skybound Entertainment/Valhalla Entertainment/AMC Networks/Entertainment One

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in