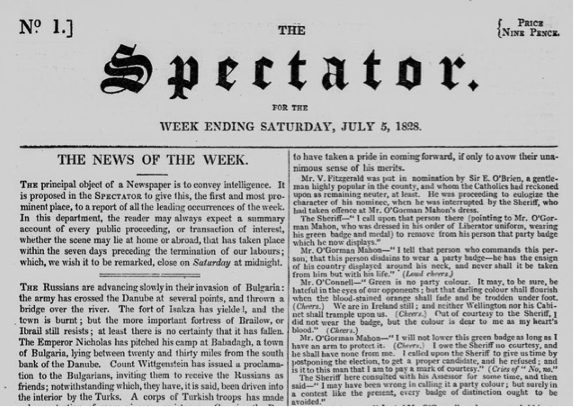

This weekend The Spectator reaches a truly historic milestone. For forty years, it has been the oldest current-affairs or literary magazine in the UK, since Blackwood’s Magazine (1817-1980) at last came to an end. But now, in its 2,300th month, it becomes the longest-running news magazine in the world, taking that title from the journal that started the genre.

The Gentleman’s Magazine that appeared in 1731 was not just any magazine: it was the venture that first launched this word in print, repurposing the French/Arabic magasin/makhazin (‘storehouse’) to describe its novel medley of current affairs, news gazette, literary criticism and antiquarian speculation. (While the original Spectator, founded by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele twenty years earlier, was an amalgam of individual essays on all and sundry subjects, it was in no sense a journal of news.)

Devised by the printer and inventor Edward Cave (1691-1754) – under the optimistic pseudonym of ‘Sylvanus Urban, Gent.’ – The Gentleman’s Magazine, or, Monthly Intelligencer sought to cover every topic of potential interest to the British reading classes. As it told its Georgian audience, it offered a monthly

View of all the pieces of Wit, Humour, or Intelligence, daily offer’d to the Publick in the News-papers, (which are of late so multiply’d as to render it impossible, unless a man makes it a business, to consult them all) and in the next place we shall join therewith some other matters of Use or Amusement that will be communicated to us.

Working from his home-cum-office at St John’s Gate, London, Cave threw together reports from the disparate journals of the day, gave extensive reviews of new publications, reported on the muffled goings-on within Parliament, surveyed current affairs at home and abroad, and commissioned notoriously detailed obituaries of the great and the good. An early coup was to appoint Samuel Johnson to its writing staff, who brought some much-needed satirical bite as parliamentary editor (1740-4).

For most of its existence, each volume of a 100-odd pages served as the periodical of general record for the activity of the nation’s gentry and the burgeoning waves of men-on-the-up. While its fascination with British history and obscure country traditions was unrelenting, it also gave ample space over to poetry, literary criticism and correspondence. In the nineteenth century, its team of writers included the likes of Coleridge, Lamb, Hazlitt, Dickens and Ruskin. But, for all this journalistic firepower, competition from other more inventive titles became increasingly intense: The Athenaeum, Macmillan’s Magazine, Saturday Review and The Spectator inevitably eroded the space the Gentleman’s Magazine had first designed.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, despite a new publisher rebilling the magazine as an ‘Entirely New Series’ in 1868, the journal’s energies were flagging. The frequent serialisation of new novels helped slow the decline but it was not enough. Worse was to come in the 1880s, when it lost its famous engravings and illustrations; soon after it lacked the resources to pay for fresh fiction. Despite its readership being comfortably above 10,000 for most of the Victorian era, when the twentieth century arrived it had fallen to below 1,000 and the writing was on the wall. Meanwhile, The Spectator, which had been in existence for three-quarters of a century, had steadily risen to be the most popular weekly in the country. Accordingly, when the public angrily debated the ‘definition of a gentleman’, this was the gentleman’s magazine in which it happened.

The end was nigh, and seemed to come in September 1907, when the last proper issue of the Gentleman’s Magazine appeared. The journal now had nothing distinct to show for itself, other than real pride in its past. Over its long succession of editors – the Cave and Nichols families, followed by Joseph Hatton and Joseph Knight – it could boast a then unparalleled history of 176 years and 2121 issues in print. Indeed, this momentum took some stopping, as the title continued to limp on: for the next fifteen years (September 1907 to September 1922), a four-page bifolium appeared each month, almost entirely devoid of contents. The strategy was partly romantic – to keep the dream alive – but primarily commercial: so long as these ghost issues were lodged at copyright libraries, the premium title of ‘The Gentleman’s Magazine’ was legally protected. By 1922 this rather desperate measure had become a grim joke, and with a whimper the world’s first ‘magazine’ disappeared for good.

A century down the line, and The Spectator is not just the world’s oldest weekly magazine, but also the world’s longest-lasting current affairs magazine, having now survived for 69,985 days. More remarkably, it is very soon to reach the unparalleled achievement of its 10,000th issue, which will appear on St George’s Day (23 April). There are, of course, older English newspapers (led by Berrow’s Worcester Journal, 1690-), and older specialist publications – such as the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (1665-), Lloyd’s List (1734-), Curtis’ Botanical Magazine (1787-), the religious Gospel Magazine (1796-), the Philosophical Magazine (1798-), and the medical Lancet (1823-). But, in current affairs, The Spectator’s global record looks set to last.

David Butterfield is a Fellow of Queens’ College, Cambridge; 10,000 Not Out, his history of The Spectator, is due to appear this April.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in