In the days before Christmas 2019, thousands of tourists flooded into the township of Mallacoota, close to the New South Wales-Victorian border. The picturesque town is immensely popular at holiday time, with the regular population often swelling from just 1,000 to over 9,000. The town is accessible by a single road snaking some 25 km through thick forest to the Princes Highway.

Little did these holidaymakers know that they were destined for a firestorm of biblical proportions.

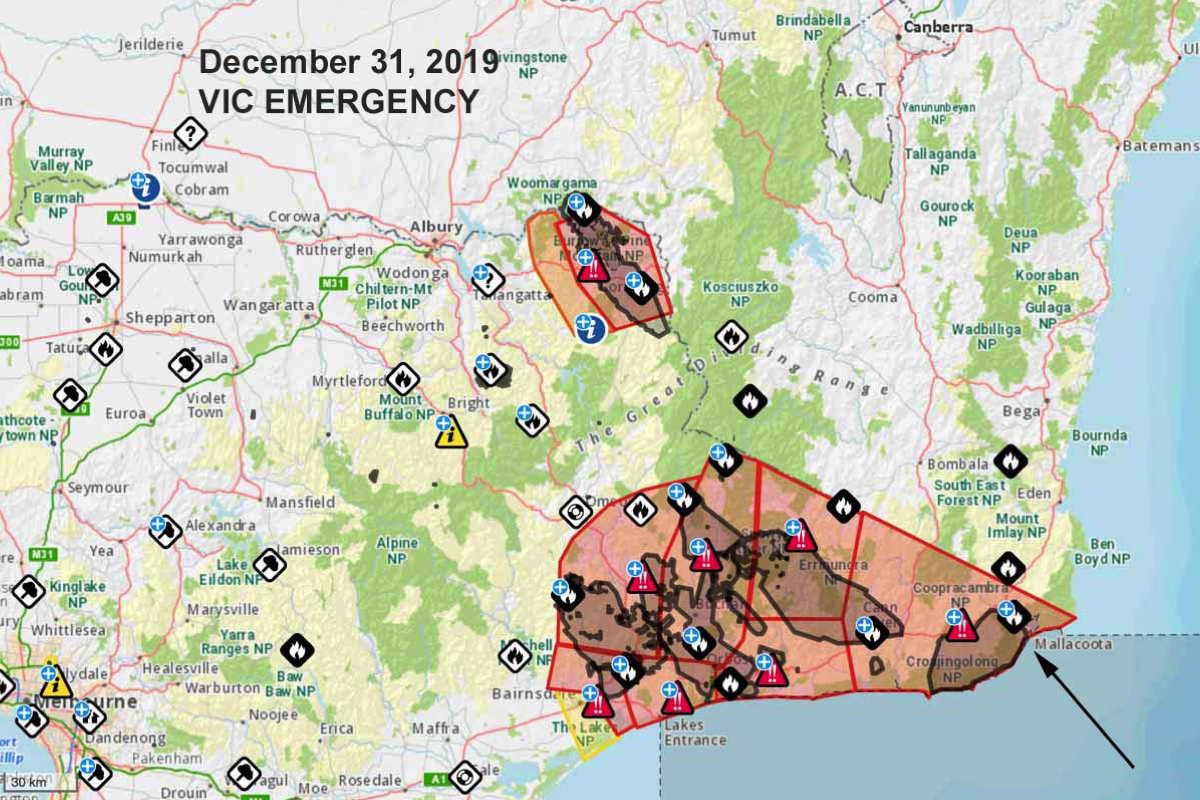

Fires originating in the Croajingolong National Park, west of Mallacoota, had grown out of control on the weekend of December 28-29, and by Monday authorities had decided it was not safe to attempt to evacuate people from the town. Country Fire Authority volunteers worked courageously but unsuccessfully to control the blazes. However, by New Year’s Day the fire had reached the town, and the firefighters were forced to withdraw to last-ditch positions protecting people sheltering on the beach with the sea behind them and the fires in front of them.

The stories and images for the fire are etched in our memories: walls of flame, the courage of the firefighters, the fears of families taking to boats or huddled on the beach, and their ultimate rescue by the ADF. But none of this should have happened.

Few of the people trapped in Mallacoota would realise that their days of terror were the consequence of bureaucratic policies which tolerated the residual fire risk in the district rising to manifestly dangerous levels. It can now be shown how and why this was allowed to occur.

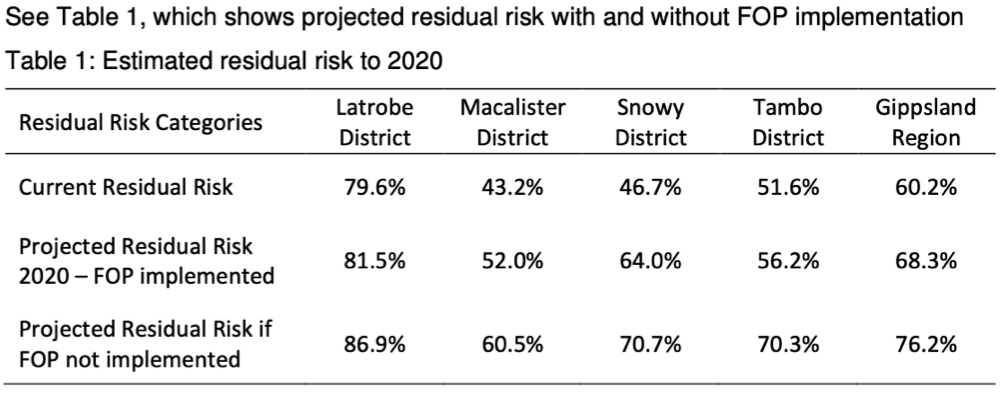

Rural Victoria is divided into six fire regions, each of which is covered by a Fire Operations Plan that governs how the risk of fire is supposed to be managed.

The current Fire Operations Plan for the Gippsland region was put in place in 2017. It was intended to cover the two years from 2017-18 to 2019-20. It breaks the region into four districts, one of which is the Snowy district in which Mallacoota is situated.

The Gippsland region’s Fire Operations Plan sets out the priorities and principles for fire management, as well as detailed schedules for controlled burning. The objective of the Fire Management Plan is to control the residual risk of fires. It says: “Residual risk, is the risk, on average, that bushfires will impact on life and property across the landscape. It is expressed as the percentage of the risk that remains after bushfire history and fuel management (mainly planned burning) activities are considered.”

The only problem is that the Fire Operations Plan for the Snowy district specifically planned for the residual fire risk to rise from 46.7 to 64 per cent over the two year period, as this table taken from the Fire Operations Plan shows.

The idea that a fire management plan should not merely tolerate a 64 per cent risk of fire impacting “on life and property across the landscape,” but allow the risk to rise disturbingly fast to that level is simply unimaginable.

Equally unimaginable is the extremely limited extent to which controlled burning was intended to limit the residual risk of fires. In the Snowy district, the fire operations plan was supposed to reduce the residual risk of fire by just 6.7 per cent over two years.

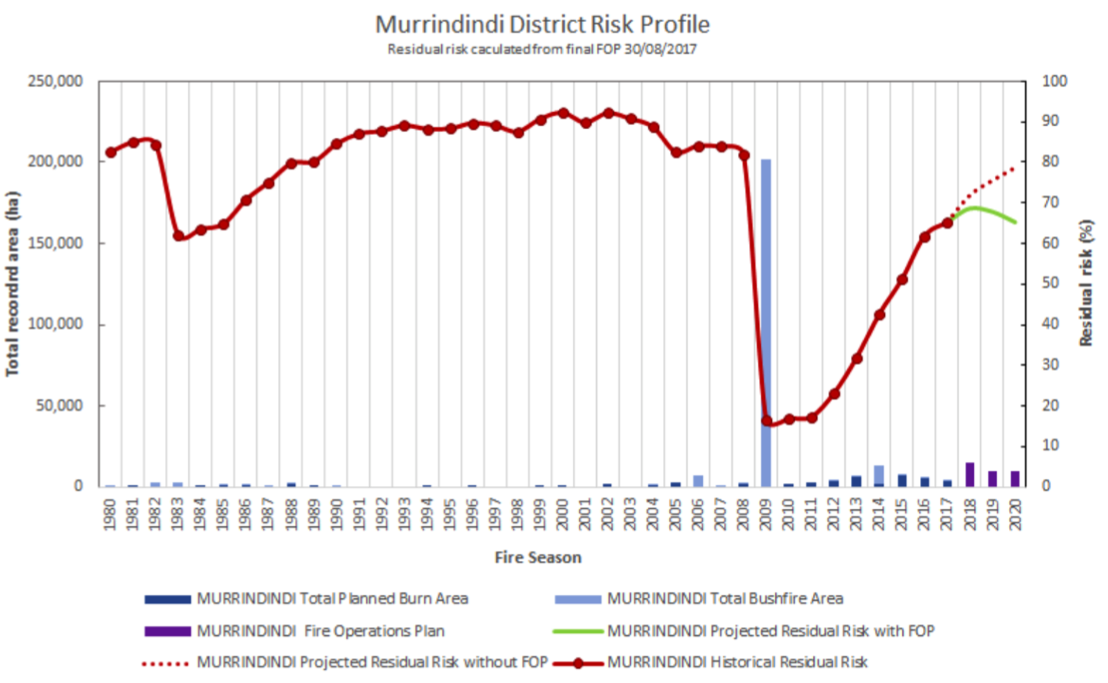

The Gippsland region is not alone in this regard. The Fire Operations Plan for the neighbouring Hume region is just as alarming. All of the districts comprising the Hume region have experienced significant bushfires in the last fifteen or so years. Bushfires burnt almost 250,000 hectares in the Upper Murray district in 2003; some 170,000 ha were burnt in the Goulburn district in 2007, and 200,000 ha were destroyed in the Murrindindi district in 2009.

In the intervening period, the residual fire risk in all these districts has been allowed to rise to levels near those when they last experienced major bushfires. Common sense dictates that this is not just unwise but unacceptably dangerous. In the Murrindindi district, the residual fire risk has risen from less than 20 per cent in 2011 to near 70 per cent, as shown in the graph below from the Fire Operations Plan.

Despite international media attention, the recent fires in NSW and Victoria are not Australia’s worst. As Dr Neil Burrows points out, in February 1851 fires burnt five million ha of country in Victoria and took 12 lives. In 1939 two million ha of Victoria were burnt and 71 people were killed. The Ash Wednesday of 1983 fires led to the deaths of 47 people and left 200,000 ha burnt, and in 2009 the Black Saturday fires claimed 180 lives.

The 2009 bushfires led to a Royal Commission which examined the causes of the blazes and sought to make recommendations to prevent similar catastrophes occurring again. The Royal Commission made 67 recommendations, but repeatedly declared the guiding principle behind all of them was that “the protection of human life should always be the overriding objective.”

Ten years later this clear principle has been so subverted such that protecting human life and property is just one of three objectives of Victorian Fire Management Plans, alongside “maintaining and enhancing ecosystem resilience” and “achieving other desired outcomes as identified by communities.”

It should be obvious that any public official who attempts to “balance” these competing interests will of necessity make decisions which do not make protecting human life the overriding objective, and in so doing, they put people’s lives at risk. There seem reasonable grounds to suspect that some of the lives lost in Victoria might have been saved had this not been so.

How did this come to be? In part because successive governments in Victoria have failed to enshrine the recommendations of the Royal Commission in legislation. Instead, decisions relating to public land are hamstrung by the provisions of Victoria’s Environment Protection Act 1970. These include requirements to consider biological diversity and intergenerational equity, in decision making. These requirements have the effect of subordinating the protection of human life to environmental miscalculations.

In Mallacoota, the arrival of the firefront on New Year’s Eve was presaged by plumes of smoke rising 12 kilometres into the air. Given wing by these winds, fiery embers travelled huge distances before finally falling to ground and starting new fires.

Local resident and community radio presenter, Francesca Winterton was broadcasting from the town at the time, and described the scenes.

“It’s not pleasant, it’s pitch dark here and the emergency vehicles have disappeared from sight,” she said.

“My home’s in the fire path, I won’t have a home, that’s just the way it’s going to be, we have to try and be calm.”

The fires that threatened Mallacoota had spread across thousands of hectares of bone dry land which should have been subject to fire reduction burning but had been left untouched. These included areas of long undisturbed vegetation, those that provided a habitat for the Leadbetter’s Possum, and areas that were deemed to have little bushfire reduction value. Additionally, there had been minimal burning in some 70 per cent of public land that was deemed to be “below minimum tolerable fire interval”. The exclusion of these lands was the consequence of Victoria’s overdone environmental polices.

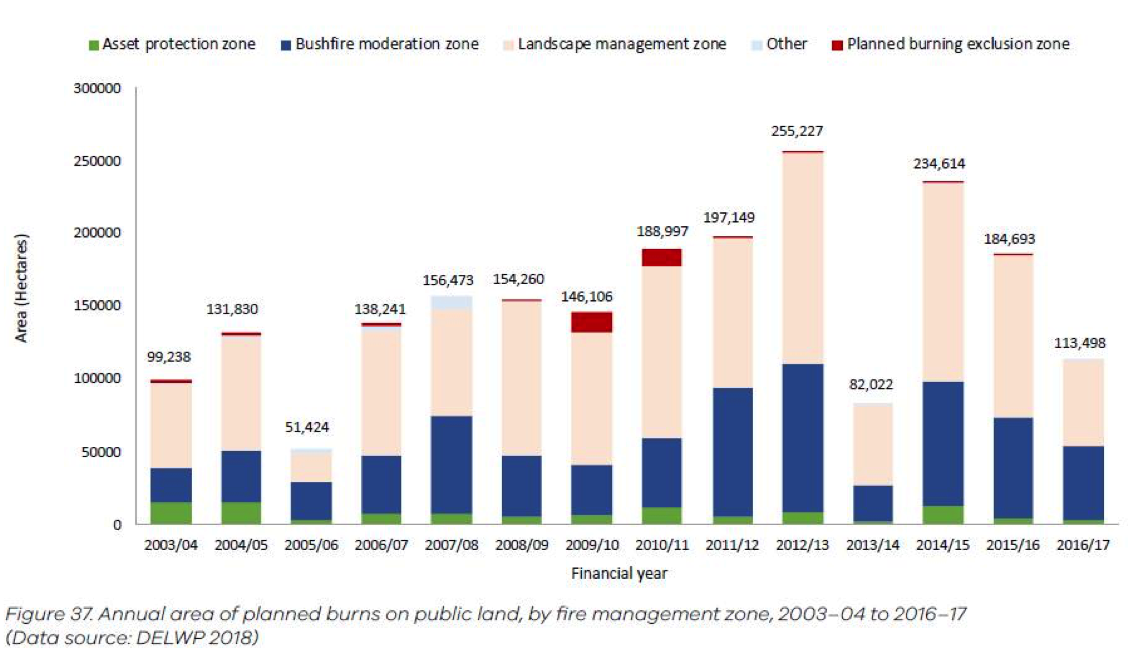

This was not the intention of the Royal Commission, which recommended that a plan of prescribed burning “with an annual rolling target of a minimum of five per cent of public land each year.” However, the Gippsland Fire Operations Plan involved burning just 5.3 per cent of public land over a period of three years.

One of Australia’s most recognised practitioners in forestry management, Dr Gary Bacon AM, points out that it is not just in the Gippsland region, but across Victoria that the government has failed in meeting its fire management obligations. To meet the Royal Commission’s minimum recommendations, 385,000 ha of public land needs fire reduction burning each year.

“Since the 2009 Commission the DSE has burnt on average 2.1 per cent of the crown estate each year, Bacon told The Spectator Australia. “This is well below the amount bushfire experts Phil Chaney and Roger Underwood, and previous inquiries have suggested is needed to reduce social, infrastructure and environmental risks, including the health and sustainability of ecosystems, in the long term.

“Not scheduling burning in areas of long undisturbed vegetation is “utterly inappropriate.”

This has catastrophic and fatal consequences.

“Fuel load is the only metric that we humans can control and it is the most influential component in the fire making process. A doubling of fuel quantity raises the intensity of a fire by a factor of four,” Bacon explained.

On the other side of the world, several dozen protesters assembled recently outside the Australian High Commission in London, to blame the fires on perceived deficiencies in Australia’s emissions reductions.

One of the protesters, 76-year-old Peter Cole, told Reuters: “I’m here because the Australian government is doing absolutely nothing to combat climate change. In fact they’re largely denying it and they need to be put under a lot of pressure…”

Cole and his fellow protesters, for all their good intentions, clearly do not understand the crisis about which they are protesting. They do not understand that these fires are just another chapter in Australia’s long saga of large scale bushfires. They also do not understand climate change itself.

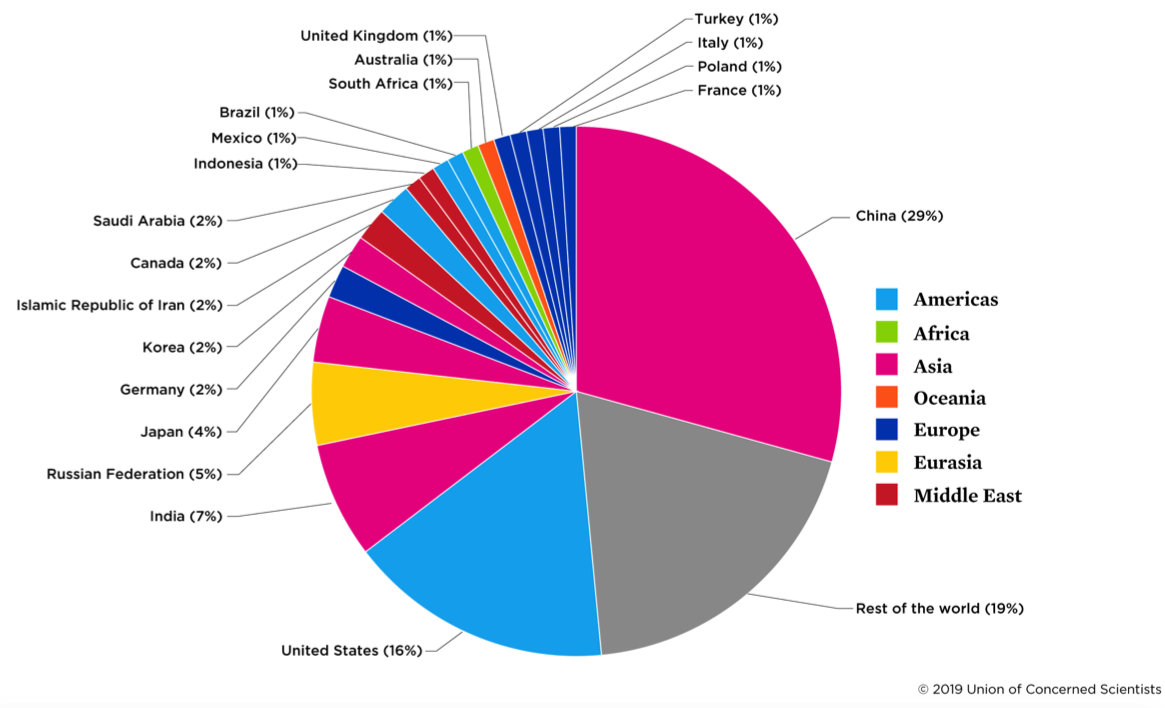

The point about global climate change is that it is just that — global. Local emissions do not drive local effects on the climate. To the extent that CO2 emissions drive climate change, they would be better protesting against Germany’s culpability for the fires, or Japan’s, India’s, Russia’s, or Heaven forbid, China’s culpability.

It is some 25 years since I was the first person to speak in the joint party room in Canberra about climate change and the need to respond to it.

Climate change — by which I mean greater climate volatility, which is far more dangerous than mere global warming — has no easy solutions. If it did, they would have been taken by now.

What was apparent to me 25 years ago, and is more apparent now, is that emissions reductions are only part of the solution. Adaptation to the effects of climate change, and how we manage the environment, are just as important, if not more so.

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists — hardly a right-wing pressure group – Australia contributes just 1.07 per cent to global emissions. However, Australia has 5.2 per cent of global land mass. That means we have little impact on global emissions, but suffer disproportionately from the actions, or inaction, of other countries. Faced with this proposition, we need to do far more to mitigate the effects of climate volatility on the Australian landscape.

The problem is that the last decade has seen reduced hazard reduction burning when we needed more. Victoria is not alone in this. Queensland recently failed to undertake its planned fire reduction burns due to environmental considerations.

Across the Eastern states, successive governments have given in to preservationist pseudoscience that says inaction is the best protection for the environment. The fires in NSW and Victoria have shown this to be a tragically misguided mantra, as hundreds of millions of animals exterminated by fires show.

Governments at all levels need to enshrine the protection of human life in legislation as the foremost consideration in fire prevention and management. They must also remove the failed environmental shibboleths which hinder this and consign them to the dead ashes of history.