With both the mainstream and the social media full of jubilation or alternatively tears about the British general election results, let me sound a characteristic Arthur Chrenkoff note of caution: what we have witnessed yesterday was the most left-wing Labour leader since Clement Atlee being defeated by the most left-wing Tory leader since Ted Heath.

It’s the testament to the crazy times we live in – not to mention how far left the left has moved – that Boris Johnson is considered some sort of a hard right populist xenophobe. The reality is quite different; as a fellow Oxonian, Andrew Sullivan, writes in his recent perceptive profile of Johnson,

As a longtime liberal Tory, Boris… saw the deep unpopularity of his party’s legacy of fiscal austerity and the need to shift left in economic and social policy. So he is quietly forging a new conservatism — appealing to the working poor and aspiring middle classes, tough on immigration and crime, but much more generous in spending on hospitals and schools and science. Or so he says for now. And if he succeeds — by no means a sure thing, though at this point it almost seems foolish to bet against him — he won’t just be charting a new future for the U.K. but pioneering a path for other Western parties of the center right confronted by the rise of populist extremism.

Whether Boris is a committed liberal Tory, or as both Sullivan and Mark Steyn describe him, an “unprincipled opportunist”, he has managed to on the one hand take a mass working-class following away from the Labour Party and on the other neutralise the right-populist parties like UKIP and Brexit Party. But he’s neither really a Trump clone (whether by temperament or inclination) nor a Thatcherite (again, Sullivan):

The truth is Johnson has a record as a liberal Tory: a conservative who can celebrate “our fantastic National Health Service” and has no interest in politicians’ preaching about morality. And it was this conservatism that enabled him to become mayor of London, a largely Labour city, where he thrived. He brought back the double-decker bus; launched a successful, if unprofitable, bike-sharing scheme, “Boris Bikes”; backed an amnesty for illegal immigrants; banned booze on the tube; raised the recommended living wage in London; and presided over an Olympics that became a public-relations coup for the entire country. Crime declined — as it did everywhere. And Boris became one of the most famous cyclists in the city, careening back and forth, often on his mobile phone. By the end of his term, a YouGov poll found that almost twice as many Londoners thought he did a good job as mayor as those who didn’t.

As always, Johnson’s ideological flexibility was key — so much so that it led him to resist the more doctrinaire forces in his own party. As mayor, Johnson complained about the austerity measures of the Tory Cameron government. And as prime minister, he has immediately ramped up public spending on the police, schools, and hospitals. He shelved a previous proposal to lower the corporation tax and has focused on raising the income threshold at which Brits pay the equivalent of the Social Security tax and on raising the minimum wage nationwide. He has urged people to “Buy British” — a slogan anathema to market economics. Whether this is posturing or serious, no one knows exactly, but it sure is a sharp move rhetorically left for the Tories, away from the wealthy and austerity and toward the working poor and debt.

Or as Steyn comments, “It would be nice to think that the Conservative Party might now think it safe to offer a bit of conservatism. But that would be too much to hope for…” The most right-wing things about Boris are Brexit (he was against, or at least very ambivalent, before he was for it) and some of his rhetorical flourishes, which truth be told have more to do with his self-cultivated buffoon image and a penchant for tabloid flourish than with any particular bigotry.

Personally, I’m quite fond of Boris because he is a character, which is rare these days in our over-sanitised politics, but he’s not a right-wing champion of the old, if by right-wing one means a small government economic liberal. This is perhaps because an economic “dry” would be unelectable today just as an unapologetic socialist like Corbyn has proven to be. This in itself deserves further attention.

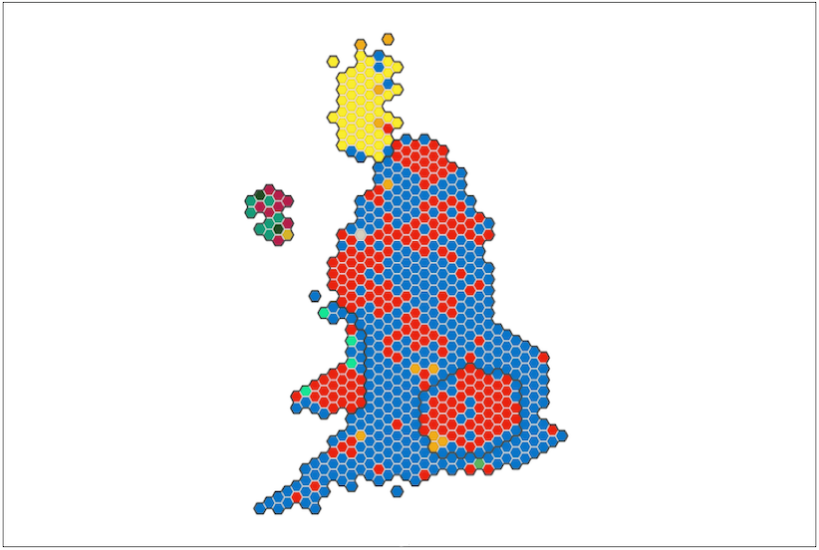

Whatever the new ideological cleavages in the 2019 electorate, they are also very much regional – Scotland almost completely dominated by the pro-independence and pro-EU leftist Scottish Nationalists, Conservatives an almost wholly English party, and Labour, to again quote Steyn, “a pantomime horse of urban redoubts – immigrant enclaves in the North and Midlands and upscale champagne-socialist quartiers of London”. In what is potentially the most dangerous development of all, nationalist representatives now outnumber unionists in Northern Ireland.

Laugh or cry in the aftermath of this December poll, the five years ahead are set to be stranger and more tumultuous than any other in recent times. To borrow from Churchill – whom Johnson resembles both in style and in policy – this is not the end, this is not the beginning of the end, but it’s perhaps the end of the beginning of the journey to the new Britain.

Arthur Chrenkoff blogs at The Daily Chrenk, where this piece also appears.

Illustration: BBC.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in