Deep in the guts of Russian library stacks exists what remains — little acknowledged or discussed — of a dead and buried atheist dream. The dream first took shape among Russian radicals of the mid-19th century, to whom the prospect of mass atheism seemed the key to Russia’s salvation. When Lenin seized power in 1917, the Bolsheviks integrated it into their vision of heaven on earth.

To the extent that people in the West have heard of this atheist dream, it has come to them mainly through the voices of its enemies. In 1983, Ronald Reagan put Lenin’s rejection of religion at the heart of Soviet unfreedom in his ‘Evil Empire’ speech. That same year, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn blamed atheism for Russia’s catastrophes in his ‘Men Have Forgotten God’ speech at the London Guildhall (in which he also lamented the blasphemies of Monty Python’s Life of Brian).

Even if the whole subject now lies under a layer of dust, visitors to Russia’s magnificent state libraries — Soviet-era temples of learning devoted to the enlightenment of the once-benighted people — can unearth volumes of vividly illustrated anti-religious magazines from the Soviet era that reveal the evolution of a godless utopia. The main anti-religious magazines of the 1920s, Godless and Godless at the Machine, were graphic declarations of war on all religions. Godless published illustrated essays on religion around the world that resembled entries in a children’s encyclopaedia. Godless at the Machine championed Marxism-infused satires and caricatures.

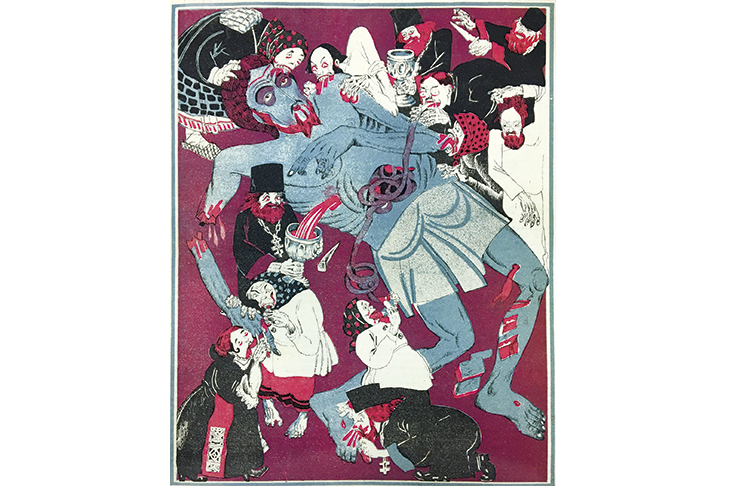

Blasphemous shock and awe were a major part of the Bolshevik aesthetic, which sought to show a still-pious nation just who was in charge. One memorable atheist illustration showed a worker climbing a ladder into the heavens above a landscape of shattered temples to smash the gods. It carried the caption: ‘We’ve finished the earthy tsars and we’re coming for the heavenly ones!’ A stylish lithograph from the same magazine showed a grisly parody of communion, with priests and peasants butchering the body of a dead Christ and eating his limbs and entrails. Some magazines ran photos of real holy corpses: the mummies and skeletons of Russian Orthodox saints which the Bolsheviks had exposed to debunk the popular belief that such relics didn’t decay.

Over the course of the 1920s, the magazines’ emphasis shifted from vivid, imaginative blasphemies to a more regimented, Stalinist genre of atheism, concerned with the construction of godless collective farms and industrial cities at the expense of religious buildings and ‘class enemies’. One Godless at the Machine cover from 1930 showed a village priest as a hungry wolf stalking the outskirts of a collective farm, reflecting the collectivisers’ habit of persecuting village priests and dressing animals in their vestments. A 1930 Godless cover showed — as if to illustrate a bad joke — a priest, a rabbi and a mullah being swept through a dam sluice. These magazines often announced the closure and demolition of ‘centres of obscurantism’ — i.e. religious buildings.

The articles in Godless — into which Godless at the Machine was folded in 1931 — showed a deep awareness of Soviet atheism’s 19th-century intellectual roots. It published features on heroes of the Bolshevik atheist canon, including Nikolai Chernyshevsky and Nikolai Dobrolyubov (both sons of priests), the first writers to deny the existence of God in Russian print. The contributors also scoured western philosophy and literature for all that was anti-religious or anti-clerical, from Hobbes and Shakespeare to Voltaire and Victor Hugo (whose novels a young Josef Stalin was punished for reading during his grim training for the Orthodox priesthood in Tbilisi).

Stalin abandoned the atheist dream when Hitler invaded the USSR in June 1941—when anti-religious publishing ceased more or less entirely — in favour of an Orthodox-tinted ‘sacred’ struggle against fascism. But the Communist party revived it in the wake of Stalin’s death and Khrushchev’s de-Stalinisation campaigns of the late 1950s and early 1960s, during which atheism seemed a handy signifier of a determined return to Marxist-Leninist roots and a renewed faith in communism. The anti-religious imagery of the Khrushchev era celebrated the glories of the space race — with workers’ sons now storming the heavens in rocket ships — and denounced the greed of village priests and the perceived threat of religious minorities such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Soviet satirists struggled to understand the persistence of religion in a now-urbanised, literate country where so many churches had been replaced by gleaming libraries, theatres and TV towers. They showed, too, a deep resentment of the West’s concern with religious freedom in the USSR (which they portrayed as a front for espionage), and of ungrateful jeans-wearing Russian hipsters who flashed crucifixes as symbols of rebellion. The Russian atheist dream died with glasnost, and now enjoys little popular nostalgia. Yet today, the Russian authorities often react touchily to public displays of irreligious irreverence; to them, flirtations with godlessness seem synonymous with revolution.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in