Boris Johnson thrives on risk. His political life so far has consisted of a succession of gambles that have paid off: leaving the Commons to be Tory mayoral candidate in a Labour-voting city; choosing Leave in the referendum against the odds and the establishment; resigning as foreign secretary; and then becoming Prime Minister when many thought he was a busted flush. These decisions are the marks of a man from whom we ought to expect the unexpected. And there is good reason for him to now make the ultimate bet and call a snap election.

It’s now widely assumed that Jeremy Corbyn will table a motion of no confidence soon after Parliament returns from summer. As I wrote on Coffee House this week, the anti no-dealers’ best strategy is to use such a vote, in combination with legislation, to force the PM to seek an extension to Article 50 at the EU Council summit of October 17. The EU would surely grant such an extension, and a document leaked to the Times this week suggests this is exactly the plan of attack.

To make this strategy even more dangerous for Boris Johnson, MPs could, during the two-week period granted after a vote of no confidence for MPs to try and form an alternative government, legislate to amend the Fixed-term Parliaments Act. This period would allow those determined to block no deal a chance to remove the PM’s control over the election date.

Of course, there is a possibility that the motion of no confidence does not pass the first time round. Or Jeremy Corbyn could surprise people, as he promised to do before the summer recess, keeping his powder dry and holding off on a vote of no confidence. This could come after the party conferences, when Parliament returns on October 9. Or after the EU Council summit, assuming there is no new Brexit deal. In either case, the close proximity to exit day, with jittery markets and a tanking pound, would mean that the anti no-dealers are likely to prevail, either in forming an alternative government or by passing laws in parliament to disrupt Boris’s strategy.

Johnson, however, can pre-empt such manoeuvres on September 4 when Parliament returns by tabling a motion for an early general election, to be held on October 10.

This date is opportune for two reasons. First, Parliament would dissolve by law on September 5. This immediately eliminates the threat of MPs taking control of parliamentary time, keeping the exit date of October 31 intact.

Second, this election date comes a week before the EU Council summit. If his gamble pays off and he were to win a majority, the PM would have the strong negotiating position required to obtain a new deal. If the EU still refuses to budge, the Government could spend the final weeks passing relevant no-deal legislation to minimise disruption before Britain leaves the EU.

There is, of course, the question of whether Boris can win a snap election. But although there is a risk for the PM here, politically this strategy makes sense. The Conservative party conference will be a Brexit rally behind Boris Johnson. Labour will no longer be able to triangulate its position on Brexit. This would surely mean fireworks at their gathering in Brighton.

Would Jeremy Corbyn pursue a policy of a second referendum and campaign to Remain – thereby alienating the party’s core support and competing for the same slice of electoral pie as the resurgent and consistent Lib Dems? Or would Corbyn continue with the sludge of a “jobs-first Brexit” – and alienate the Labour membership and the majority of the parliamentary party?

Another advantage for Boris in these circumstances could be that the Brexit party chooses to be a help, rather than a hindrance, to the Tories. Surely Nigel Farage’s party would not scupper the whole project by standing candidates in seats where October 31 “do or die” Tories have the best chance of winning?

The risk of holding an election before October 31 should, in any case, be judged against the narrowness of Boris Johnson’s other options. The Government’s only viable counter-strategy to anti no-dealers while Parliament is in session is to prorogue it. This would be the surest way to restart negotiations with the EU; Parliament can be recalled at any time while prorogued in order to vote on a new agreement. If this achieved a deal without the backstop, the decision to prorogue would retrospectively attract significant approval, as it would prove that MPs had been obstructing the Government from negotiating an outcome for which there was already a majority (demonstrated by the Brady amendment back in January).

What’s more, while some MPs thought they had succeeded in preventing prorogation from happening, put simply, they hadn’t. These MPs hoped that they had blocked this option by inserting measures into the Northern Ireland bill to compel the Government, every 14 days from October 9, to lay before Parliament a report on the progress of talks to restore the NI Assembly, and to move a motion on the report in both Houses (and if Parliament was prorogued on the necessary day of compliance, it would have to meet on that day and for the following five weekdays). But the Government can get round this by laying the report, then moving the motions at the beginning of the next day, and then immediately proroguing Parliament again. This would comply with the terms of the Act and considerably cut down the time for MPs to take anti no-deal measures. Dominic Grieve, it seems, has overestimated his powers of ingenuity.

However, although Boris Johnson hasn’t ruled out prorogation he has been dismissive of the idea. As proroguing is a “reserve power”, the Queen is not bound by her ministers’ advice. This means that the decision to prorogue would effectively be hers. With John Bercow pledging to ‘fight with every breath in my body’ to prevent prorogation happening, it seems all too inevitable that Her Majesty could be dragged into politics if her PM suggests this.

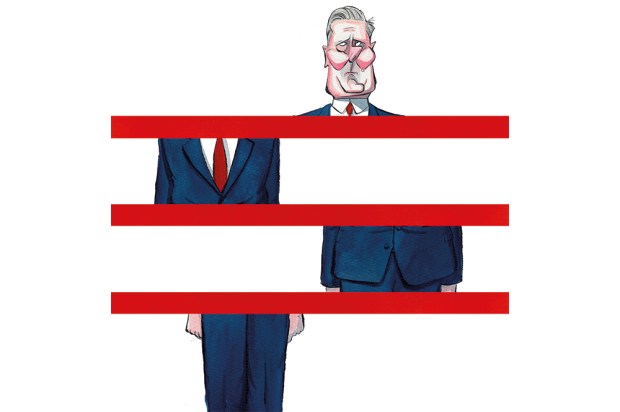

If Boris Johnson wants to avoid that, his options then come down to this: be forced to fight an election with the Brexit can further kicked down the road. Or choose to fight an election on his own terms.

As long as the EU believes Parliament can frustrate no deal, it has little incentive to re-open negotiations. As long as anti no-dealers are organised and sufficient in number, the Government will be unable to deliver an October 31 exit. When the potential weakness of its position becomes apparent, it will be better to strike with a bold move, taking advantage of opponents’ disunity, rather than waiting for events to take over as they did while Theresa May was in charge. “The point of winning is not to imitate the losers,” said Alexander the Great. Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson should dare to emulate his namesake. History may judge him great for it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in