Amazon rain forest is burning in Brazil and people are angry:

When a fire tore through Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris earlier this year, donations poured in across the world at such a rapid rate, more than one billion was raised in just two days.

The world was made aware of the catastrophe within three minutes of the first flame…

Well, another horrific fire is burning in one of the world’s most crucial natural landmarks — but it’s taken three weeks for the world to really take note.

The world hasn’t stopped. In fact, it’s only just started to get some attention, despite more than one-and-a-half soccer fields being destroyed every minute.

There are several reasons for that. Firstly, Notre Dame is one of the world’s most famous buildings and tourist attractions in the middle of one of the world’s most visited cities. The Amazon, on the other hand, is pretty far from everywhere. Secondly, Notre Dame is a man-made masterpiece and people tend to be more affected by damage to historical heritage than to nature. Thirdly, Notre Dame is unique; rain forest is not. Fourthly, flowing from the previous point, Notre Dame is irreplaceable and very difficult to repair, whereas rain forests can be regrown, however difficult that process might be. Finally – and perhaps most importantly – unlike Notre Dame, Amazon rain forest burns every year.

The fires at the moment are no doubt terrible and all efforts must be made to extinguish them, but arguably it’s not quite an ecological apocalypse that will wipe out “the lungs of the world”. It’s time to act, but it’s not time to panic.

In line with that, here a few things to keep in mind. Contrary to some overheated commentary, fires have nothing to do with climate change. Most of them have been deliberately lit by farmers and graziers to clear land. You can blame the global demand for beef for that, but that is a separate issue. Brazil needs to more successfully juggle managing its rain forest, which is a global good, and managing its farmers, who are more interested in putting bread on the family table.

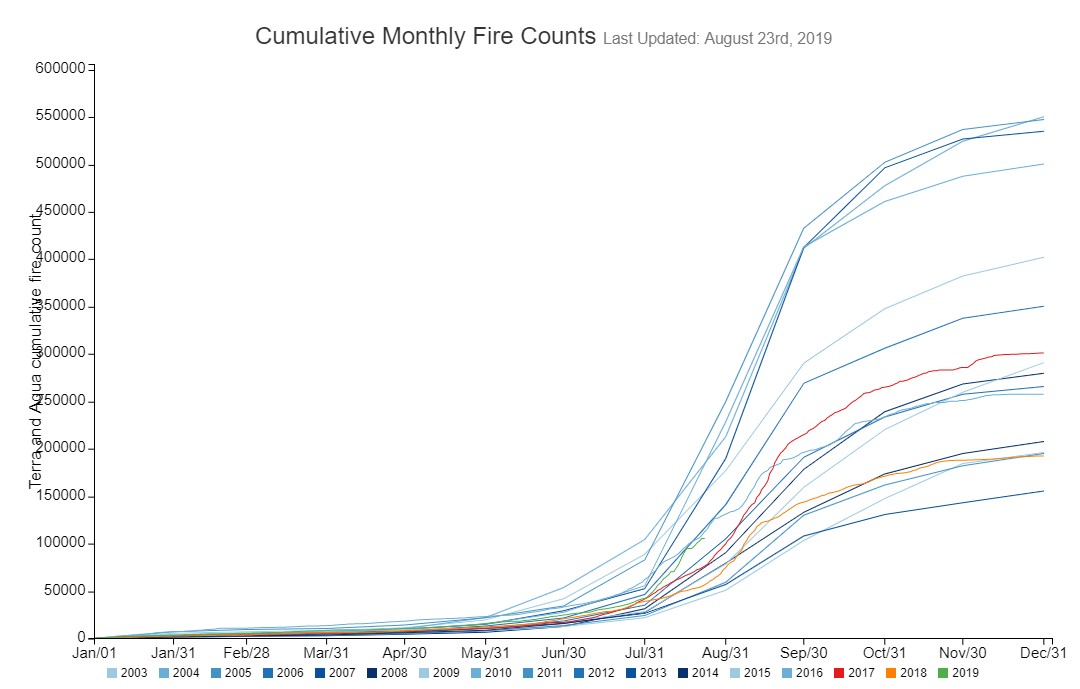

Fires are a yearly occurrence in the Amazon, both man-made and (much less so) natural, every dry season. How exceptional is this year?

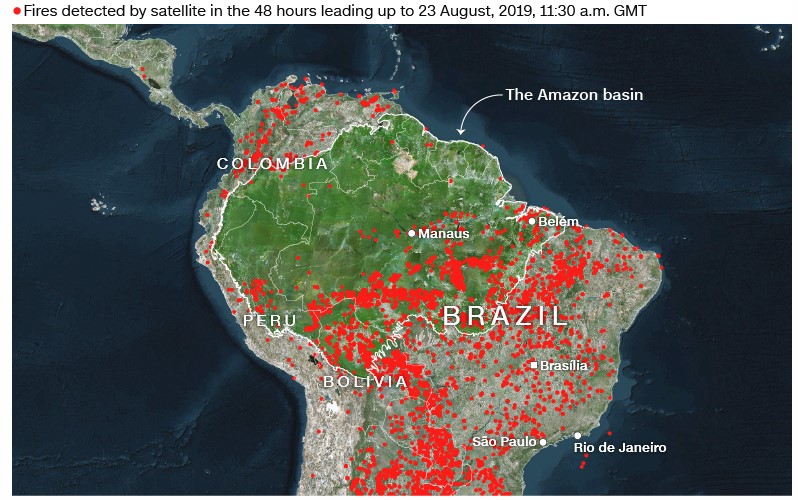

Note that this point in time, August 24, this year (green line) is pretty much in the middle range for the past 15 years. There are two caveats to add to this, however: the table covers the entire Amazon region, not just the Brazilian part of it (though if Brazilian fires are exceptional this year, this means that the rest of the Amazon is exceptionally fire-free – which seems to be the case judging from the graphic below), and secondly, this is a fire count, and doesn’t tell us in a straightforward way about the cumulative area affected.

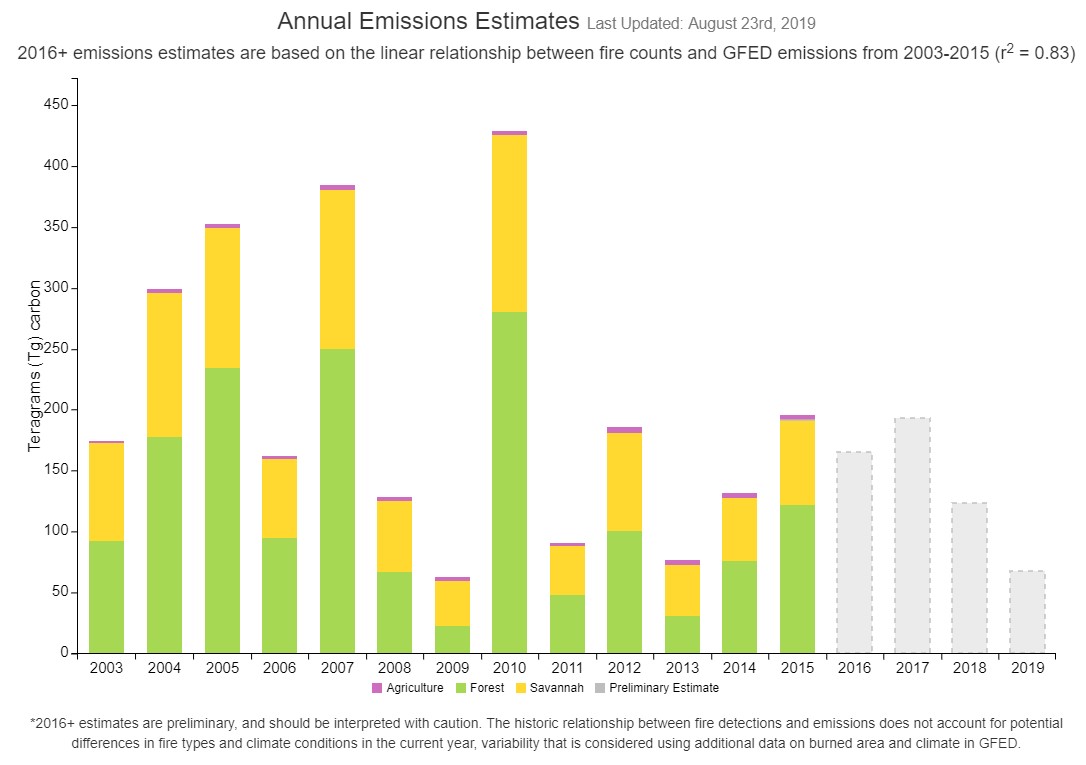

How bad is it in terms of the carbon released into the atmosphere – a proxy of sorts for the severity of the fires? Again, some caution is needed as we are talking about estimates here, but if these estimates are correct, the 2019 dry season is actually not as bad as it seems.

As NASA comments: “It is not unusual to see fires in Brazil at this time of year due to high temperatures and low humidity. Time will tell if this year is a record-breaking or just within normal limits.” So far – despite all the media attention – it seems to be the latter, but it might of course still change.

And celebrities, once again and not surprisingly, are not helping:

Many high-profile figures seeking to denounce the fires in the Amazon — from Madonna and Cristiano Ronaldo to Leonardo DiCaprio and Emmanuel Macron — have unwittingly ended up misleading millions on social media, either sharing photographs of the region that are years old or images taken in other parts of the world.

One example among many cited:

“Our house is on fire. Literally. The Amazon, the lung of our planet which produces 20 percent of our oxygen is burning,” France’s President Emmanuel Macron said on Twitter, posting a photograph of a burning forest accompanied by the hashtag #ActForTheAmazon.

“It is an international crisis. Members of the G7, let’s talk in two days about this emergency,” Macron said ahead of a planned summit this weekend in Biarritz.

But the photograph used by the French leader does not show this year’s fires. A reverse image search showed that it was taken by the American photojournalist Loren McIntyre, known for his work for National Geographic.

Although the image search tool does not reveal when exactly the photograph was taken, McIntyre died in 2003, meaning the image is at least 16 years old.

One can argue that a catastrophic fire is a catastrophic fire, regardless of what photo is used to illustrate it (and without being too arborialist about it, all rain forest looks pretty much the same), but it’s nevertheless indicative of the usual rush to panic, which can be seen in itself as another type of a celebrity virtue signal. And in this rush, facts often get lost and the reality plays the second fiddle to posturing and concern (however sincere).

As I said before, rain forests are important, fires (especially those deliberately lit) are a problem that needs to be addressed seriously, and we should not be complacent. But turning every weather event or a disaster (whether natural or man-made) into an unprecedented catastrophe that is another signpost on the road to hell needlessly terrifies some while desensitising others, and does little to solve the underlying problems.

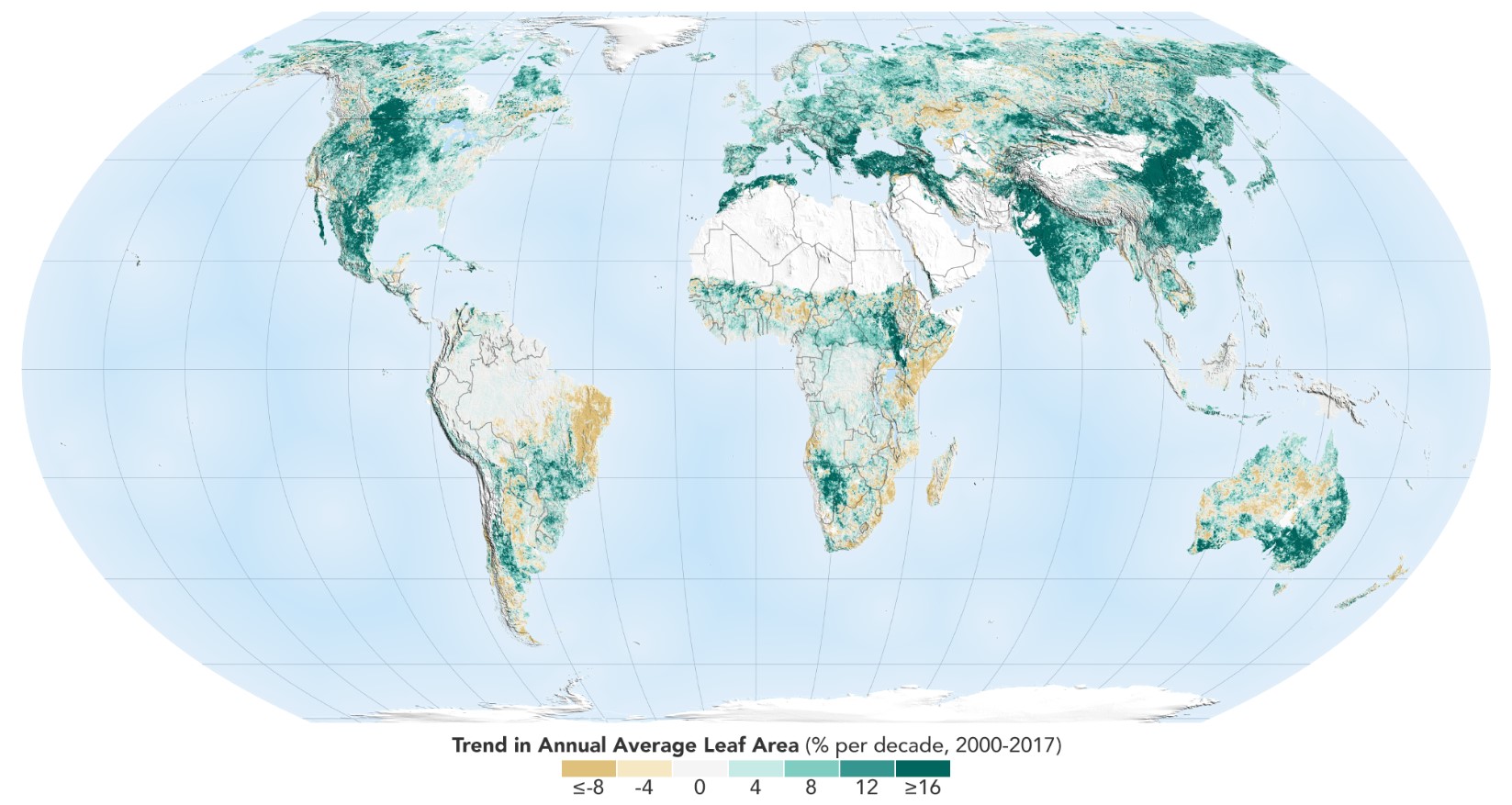

But, the good news is that the world is greener than it was 20 years ago and it keeps getting greener.

Reason magazine states:

So why are there so many fires? “Natural fires in the Amazon are rare, and the majority of these fires were set by farmers preparing Amazon-adjacent farmland for next year’s crops and pasture,” soberly explains The New York Times. “Much of the land that is burning was not old-growth rain forest, but land that had already been cleared of trees and set for agricultural use.”

It is routine for farmers and ranchers in tropical areas burn their fields to control pests and weeds and to encourage new growth in pastures.

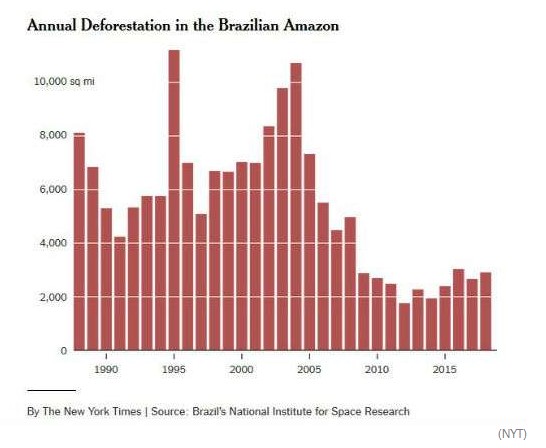

What about deforestation trends? Since the right-wing nationalist Jair Bolsonaro became Brazil’s president, rainforest deforestation rates have increased a bit, but they are still way below their earlier highs:

Various researchers have noted a U-shaped relation between environmental degradation and economic growth. As development takes off, levels of pollution and land degradation rise, but they begin to improve once certain thresholds of per capita incomes are attained. A 2012 study found, after parsing data from 52 developing countries between 1972 and 2003, that deforestation increases until average income levels reach about $3,100 per capita. As it happens, Brazilian per capita incomes reached $3,600 per capita in 2004, which is when deforestation rates began trending decisively downward.

Arthur Chrenkoff blogs at The Daily Chrenk, where this piece also appears.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in