Does the arrival of Boris Johnson in Downing Street signal the end of the politics of branding and the beginning of the politics of principle? Can we already see in the announcements and actions of the Johnson Government a new style of politics?

The early signs would suggest so. Boris’s first speech outside No.10 was devoid of fluff. The promises – extra police, delivering Brexit on time – were clear and precise and will provide an easy way to judge his record.

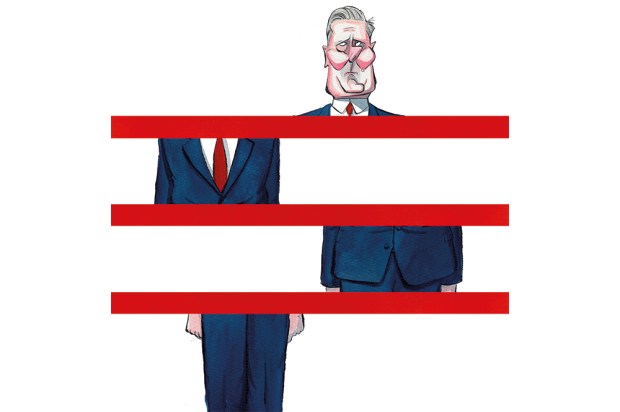

Another source of optimism is the clear difference between Boris and his predecessor. Whereas May stirred up resentments with misleading gender pay gap publications and talk of burning injustices, Boris seems eager to ditch the spin and take steps to make society more even. Of course, Boris has only been in office for a few days – and things could change for the worse. But it looks possible that PM Boris could kill off the politics of branding for good.

If so, it’s about time. This era of branding began with Clinton in America. It was copied initially by Blair, and later by Cameron and May. The US Democrats faced the same problem as the British Labour party. There were not enough members of the working class to vote Democrat or Labour out of sheer loyalty.

The remedy adopted in both America and Britain had two elements. The first was based on deployment of advertising techniques to sell their ‘brand’. They calculated that some people would never vote for them and that some would always vote for them.

They could ignore the interests of the working class loyalists who had ‘nowhere else to go’ and find out through focus groups what the floating voters wanted. Party platforms would offer them what they sought regardless of the traditional policy commitment of the party.

In America, the most notorious example was Clinton’s support for the 1996 welfare reforms, previously strongly opposed by Democrats. Blair’s equivalent was supporting NHS reform that treated the NHS as a consumer service that was too dominated by producer interests. Doctors and nurses were no longer dedicated public servants guided by altruism but producers with their own self-serving agenda.

The second element was to embrace the politics of identity. It was no good trying to win over voters with ‘evidence-based’ policies. People vote on sentiment and there are only a few emotions powerful enough to be useful.

Religion still weighs heavily, as does race. But hate is one of the strongest emotions and can easily be stirred up by dividing society into victim/oppressor configurations. Gradually new contrasts between victims and their oppressors began to be shaped for political exploitation: disabled versus able bodied, gay versus straight, women versus men, trans versus cis gendered.

Soon governments themselves were busy creating and maintaining the victim status of identity groups. Under Theresa May, the social construction of politically useful victimhood reached its peak with gender pay gap statistics and the race disparity audit, which used misleading statistics to create a sense of victimhood. It also pointed an accusing finger at blameless oppressors. May ensured that identity politics became central to the Tory brand. Fighting injustice was falsely defined as siding with identity groups based on spurious statistical analyses comparing their disproportionate representation in various occupations.

Yet ironically, as home secretary, May herself presided over one of the greatest genuine injustices of recent times when members of the Windrush generation were deported when they had every right to live in the UK. On immigration, the two elements of the politics of branding clashed. Floating voters wanted immigration to be controlled. It turned out that the possibility of garnering the votes of ethnic identity groups was not as politically useful as selling a message to floating voters.

Boris Johnson’s arrival has ended the ignoble era of political branding and the early signs are that we could be entering a new age of idealism. There are some key tests that will tell us whether the politics of branding has finally gone.

Brexit is the most obvious first test. Will the Government respect the majority view? The foremost interpreter of our constitution, A.V. Dicey, taught that we have a political sovereign and a legal sovereign. Parliament is the legal sovereign, but the people are the political sovereign. Both Government and Parliament should represent the majority of the people.

The second test is the challenge of ending the shameless exploitation of identity politics. Stirring up resentments in the hope of party political gain is unworthy. Instead of making political calculations about the voting advantages of inventing grievances via doubtful statistics, the Government should aim to provide opportunity for every individual regardless of the group to which they belong.

Third, will the Government abandon the assumptions of fiscal hawks, who deploy a false analogy between family budgets and national economic policy? Such commentators say that we should not add to the national debt because it will have to be paid off by our children and grandchildren. But actually investing today in new public assets is the best thing we can do for the future generations. They will continue to gain from new services and public assets long after today’s leaders are gone.

The fourth test concerns how liberty is perceived. It is common to portray freedom as nothing but selfishness. This caricature must be fought. However, one of our greatest defenders of personal freedom, Michael Polanyi, distinguished between private liberty and public liberty. What makes freedom a noble ideal is public liberty. Private liberty can mean using our freedom to advance our own interests as we think fit. Public liberty implies using our freedom to achieve public purposes, such as the advancement of knowledge, the conquest of disease, or the creation of the widely-shared prosperity.

Liberty at its best is a public ideal whose benefits can be enjoyed by all. Ayn Rand is admired by many defenders of freedom but she distorted private liberty into a defence of domination by people she regarded as superior. How we organise education is the ultimate test. Do we aim to allow some people to get ahead or to give everyone a fighting chance of success?

So dare we hope that with Boris in office, the politics of branding – with its manipulative advertising and the exploitation of grievances is over – and a new era of public liberty about to begin?

David Green is CEO of Civitas

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in