We were in a club, discussing Norman Stone, recently departed, over a meal that he would have enjoyed. Norman divided opinions. This manifested itself in his obituaries. Professor Sir Richard Evans summed up for the prosecution. He cited Norman’s failure to build on his early scholarly promise and his chronic neglect of academic duties. He concluded by quoting an old adversary of Norman’s, who described him as ‘amoral’.

This is a difficult verdict to refute. Yet it is only part of the picture. He won the enduring affection of most of his best pupils, despite — or because of — his unorthodox methods. In Norman’s Cambridge days, an earnest young man turned up for his first supervision. No Stone. Next week, ditto. Third week, the youngster arrived in a belligerent mood, determined to complain to his director of studies if there was another no-show. Knocks on the door: no reply. But just as the pupil was about to stalk off in a rage, a faint voice said ‘Come in.’ Norman, who had forgotten all about the supervision, was having a bath. Unfazed — history does not relate whether the same was true of his visitor — Norman invited him to pull up a chair and read his essay. After a couple of paragraphs, Norman exclaimed, ‘No, no, no.’ ‘What d’you mean, no, no, no?’ replied the pupil, his dander still up. ‘That’s not how the French do things.’ ‘How am I supposed to know that?’ ‘Surely you’ve been to France?’ ‘No.’ ‘Fetch me a towel.’ Twenty minutes later, they were heading for the Channel ports. Nor does history relate how many other supervisions Norman missed during his absence.

He was a life-enhancer. A university consisting entirely of Normans would collapse. But a university without eccentrics and witty sinners would be a diminished institution.

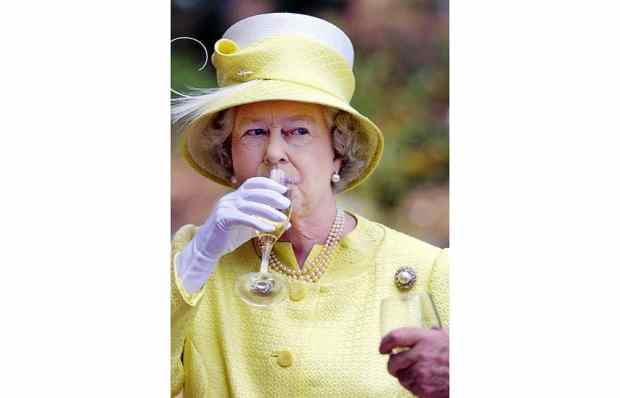

There was, however, a mystery. As Oxford was the Cavaliers’ citadel, it was far more appropriate for Norman than Roundhead Cambridge. But there are limits. By the time Oxford appointed him to a chair, Norman’s habits were well-established. It undoubtedly helped his cause that his predecessor, Richard Cobb, had been one of the more distinguished diners of his generation. He was once invited to a reception in Buckingham Palace. A chap in tights came over to prepare him to be introduced to the Queen. He sized up the situation and moved smoothly on to plan B. ‘Professor, would you like to see Her Majesty’s Winterhalters?’ So Cobb was taken down a corridor, where he admired the pictures. At the end of the passage, his escort opened a door, saying ‘Professor Cobb, your car.’

Yet Cobb never neglected his university duties. He may not have been safe in palaces, yet if he was due to lecture at 9 a.m., he would be on parade. Oxford must have assumed that the same would apply to Norman. But anyone who scheduled him for a nine o’clock lecture must have been either naive or an ironist, or both. Our deceased friend did have one principle, to which he always adhered. He was determined that duty should never take precedence over pleasure.

We took our pleasure at a new venture, a wine salon run by Quintessentially in Soho. That firm is run by oenophiles who take the trouble to track down excellent wine from diverse regions. They are now organising dinner parties at a Georgian house. Everything was stylish, including the glass. We ate beef carpaccio with summer truffles, followed by a risotto and a saddle of lamb: a two-rosette meal. After Ayala champagne, which had gained depth from extra time in bottle, we had several Italian reds from Piedmont and Tuscany. They included a couple of Barolos in the modern idiom: ready to drink when younger but losing none of that wine’s traditional depth. We finished with a Super Tuscan, a 2011 Ornellaia. Everyone agreed that this was an admirable addition to wine-lovers’ London.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in