In 2013, I started promoting a tactical voting alliance between Conservative and Ukip voters. It wasn’t just about avoiding the calamity of a Labour victory at the 2015 General Election – which looked likely then – it was also about trying to secure a parliamentary majority for an EU referendum. I called the campaign ‘Country Before Party’.

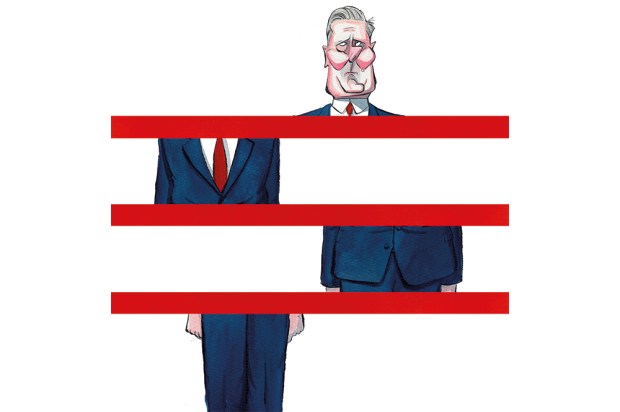

Given that a potential alliance between the Tories and the Brexit Party is something that almost half of Conservative Party members are in favour of, I thought it might be worth recounting my experience. Having once been a tub-thumper for this type of arrangement, I’m now less enthusiastic.

It’s happened before, of course. To give what feels like the most pertinent example, in 1981 a new political party entered into a formal pact with an established party, whereby each agreed not to field candidates in those seats where the other was most likely to win. The SDP-Liberal Alliance held strong for two General Elections – 1983 and 1987 – and only ended when the parties merged in 1988.

Unfortunately, it was an abject failure. In 1983, at the peak of the Alliance’s success, the two parties won only 23 seats in spite of receiving 25.4 per cent of the vote. Those votes were too evenly spread out to be translated into seats, even with the pact. Contrast the Alliance’s performance with Labour’s in 1983. In spite of polling only 27.6 per cent, Labour won 209 seats.

But that alone isn’t a reason to think a Con-Brexit Alliance would fail. It would be starting off with many more incumbents (although it’s unlikely all 314 Conservative MPs would be given a free ride by the Brexiteers) and it would probably command more than 25.4 per cent of the vote. In addition, that support is skewed in a way that’s more likely to be translated into seats.

But what are the chances of the leaders of the two parties agreeing a similar arrangement? At One Nation group hustings in the House of Commons on Tuesday, the biggest cheer went to Sajid Javid when he pooh-pooed the idea of an alliance with Nigel Farage. Most of the other leadership contenders have poured cold water on it, too. Farage hasn’t categorically ruled it out, but he has said he wouldn’t countenance a pact with Boris because he doesn’t trust him on Brexit.

That echoed my experience in 2013. I met with Farage, but he was sceptical because he didn’t trust “cast iron” Dave to honour his pledge to hold an EU referendum. Ukip had agreed not to field candidates in the 2010 election against five Conservatives – three sitting MPs and two prospective parliamentary candidates, all Eurosceptics – but that was when Malcolm Pearson was leader and even he kept the arrangement at arm’s length.

There were other objections, too, which Farage raised. Ukip was hoping to pick up lots of ex-Labour voters in 2015 and they might be put off if the party entered into a formal pact with the Tories. Then there were those Conservative refugees who made up the bulk of Ukip’s activists and who hated their previous tribe with the zeal of born-again non-smokers. Persuading them to stand down their candidates and campaign for Conservatives would be near impossible.

I didn’t discuss the idea with Cameron, but did meet with Grant Shapps, then the party chairman, and he expressed similar reservations. He pointed to a 2013 YouGov poll which showed that a Con-Ukip pact would actually help Labour. Separately, the Conservatives and Ukip polled a total of 44 per cent against Labour’s 40 per cent, but together they could only muster 35 per cent while Labour’s support climbed to 45 per cent. In particular, five per cent of those intending to vote Conservative said they’d switch to Labour in the event of a pact.

It’s a safe bet that a Con-Brexit Alliance would have a similar effect – probably large enough to see some Conservative MPs lose their seats, particularly in those constituencies in London and the South where a majority of the electorate voted Remain. (Roughly 25 per cent of Tory seats fall into that category, according to Chris Hanretty.) Even removing Brexit from the equation, there would be some moderate Tory voters who would be driven into the arms of other parties if the new leader got into bed with Farage. For that and other reasons, the chances of the Conservative party endorsing an electoral pact are remote – particularly if the leader is Boris, who will be anxious to shore up his liberal, centrist credentials.

Back in 2013, I concluded that my pact was always going to be vigorously opposed by the party leaders and I think the same today. But could there be a less formal arrangement at grass roots level?

The plan I settled on in 2013 was to draw up a list of constituencies where I thought tactical voting would have the most impact and then encourage supporters of both parties in those areas to vote for the candidate that had the best chance of winning. It didn’t matter if the national parties were opposed. My organisation would just by-pass the local officials and run a separate campaign.

But how to decide which party had the better chance? Ukip finished behind the Conservatives in every constituency in 2010, so if you based it on the previous election results there wouldn’t be a single seat in which the Kippers were in pole position. In the end I managed to scrape up 15 constituencies where you could, at a stretch, make the case for voting Ukip. Alongside them were 73 seats where I’d be urging Kippers to vote Conservative, including a ‘Dirty Dozen’ Lab-Con marginals occupied by Labour big beasts like Ed Balls.

Could a similar exercise be carried out today? This time you have last month’s European election results to base your projections on, but that gives rise to the opposite problem: the Brexit Party polled better than the Conservatives in almost every area. One policy wonk suggested to me that most Brexiteers could be persuaded to vote for Tory incumbents, provided they signed a ‘no deal’ pledge. But would that be enough?

In 2013, I wanted all the Conservative candidates I’d be supporting to sign a declaration committing them to voting for an EU referendum in the next parliament and promising to campaign for Leave. But the pledge they’d need to make this time round isn’t as straightforward.

It wouldn’t be enough for them to promise not to oppose a no-deal Brexit because that wouldn’t stop them voting for Theresa May’s deal, backstop and all. Supporters of Brexit who are united in their willingness to leave without a deal are divided when it comes to what would constitute an acceptable alternative. (Several of the no-dealers in the Conservative leadership election are proving a bit slippery on that question.) And even if the architects of the pact could agree a form of words, there would still be a trust issue. Suppose Rory Stewart took the pledge. Would bug-eyed Brexiteers trust him to honour it?

It’s that issue of trust which is so problematic. There have been plenty of these informal, bottom-up alliances in the past, most of them frowned on by national parties, but those were in the days when there were two-member towns and boroughs.

Local activists could agree on a vote-swapping arrangement between themselves, depending on which of their candidates was best placed to defeat their third preference, and then dispatch monitors on polling day to make sure the pact was being observed. In the absence of that being possible, the next best thing are neighbouring constituencies where a local pact is clearly beneficial.

In 2001, Billy Bragg organised a vote-swapping drive between Labour and Lib Dem supporters in three Conservative-held seats in Dorset and, partly as a result of his efforts, two of them changed hands – one going to Labour, the other to the Lib Dems. But the number of neighbouring constituencies where such mutually beneficial deals could be made by supporters of the Conservative and Brexit parties is probably very small.

Absent that, there’s another possibility: an app that enabled individual voters to pair up, each agreeing to vote for the other fellow’s party. The introduction of a personal, peer-to-peer element might overcome doubts people would have about such arrangements being honoured, but it still wouldn’t address the Rory Stewart issue – and that’s before you get into the bun fight about which candidates you should vote for in those seats not currently held by Conservatives. At bottom, loyalists to political parties are resistant to the idea of swapping votes because it runs counter to their sense of tribal belonging.

There are issues with the app, too. How would you stop Remainers signing on, masquerading as Brexiteers, and then ‘swapping’ with voters in other constituencies to minimise rather than maximise the chances of pro-Brexit candidates winning?

Come to that, how would you stop supporters of pro-Remain parties from using the app to forge their own election-winning alliance? Finally, if the app proved to be effective, and a Con-Brexit Alliance actually won the election, the poor people who created it would probably face a long investigation by the Electoral Commission, as well as a crowd-funded law suit by Jolyon Maugham.

I was eventually persuaded to abandon my original plan by a veteran of numerous political campaigns who convinced me that the Conservatives could win a majority in 2015 without the need for a pact and that Cameron would honour his referendum promise – both of which happened.

Does Boris Johnson (or Michael Gove or Sajid Javid) possess the necessary electoral Viagra to win an election if he’s forced by a no-confidence vote to go to the country and ask for a majority so we can finally leave?

I pray to God he does, not least because the stakes are so much higher this time. A Corbyn-led Labour Government would be worse by an order of magnitude than a Miliband-led one – a full-scale nuclear winter, rather than Chernobyl. And if Labour doesn’t win outright, but finds itself in coalition with any of the pro-Remain parties, the chances of Article 50 being revoked are high. Indeed, that might happen even if Labour gets a majority. At the very least there would be a second referendum. Whichever way you cut it, the chances of us ever leaving the EU would recede.

So I’d love to make a Con-Brexit Alliance work. (Or the Brexit-Con Alliance, as its enemies would inevitably call it.) But it’s a lot more complicated when you start drilling down into the detail. Maybe the problems I encountered in 2013 could be solved, but we probably don’t have much time. The Doomsday Clock is ticking and the fate of the UK as an independent nation states hangs in the balance.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in