Crises in the Gulf and Conservative leadership elections come around with unnerving regularity. It is not unknown for both to coincide — that happened in 1990, when Margaret Thatcher was overthrown in the lead-up to the first Gulf War. On that occasion, drama on the domestic front did not smother Britain’s response to the international crisis — unlike now.

It is bizarre to have a US president threatening to ‘obliterate’ Iran while our Foreign Secretary hardly bothers to respond, preferring to pose with fish and chips and Irn Bru on the campaign trail.

Jeremy Hunt did intervene briefly a fortnight ago, when he described Jeremy Corbyn’s refusal to accept that Iran was responsible for attacks on oil tankers in the Strait of Hormuz as ‘pathetic’. But beyond that brief clash of the Jeremys, it is hard to detect that there is any government policy on the current skirmish between the US and Iran. Were the Trump administration to go ahead with a military strike, as it nearly did last week in the wake of Iran’s downing of a US naval drone, would Britain support it or condemn it? If the crisis developed into full-scale war, would British forces join US operations, as they did twice in Iraq? Would we provide tactical support, as we did in Libya in 1986, when the first attacks were made on the Gaddafi regime? Would we sit on our hands, or would we become stern opponents? We don’t know because the government has given no indication at all. That is extraordinary.

Perhaps the government’s silence is a reflection of our loss of military power. As our forces have been run down, it has become ever harder for us to pretend that we could join a US-led operation on anything like equal terms — if indeed we wanted to.

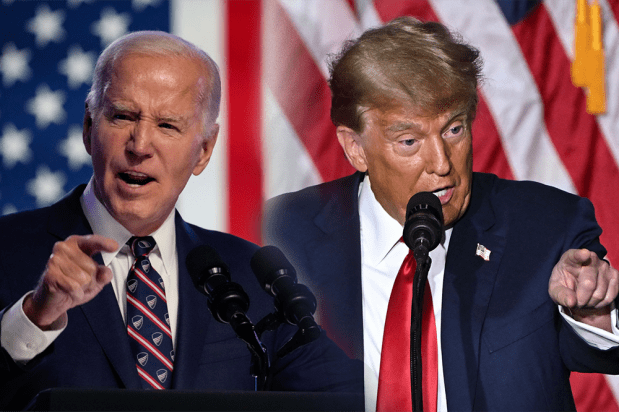

Our failure to take a position on this crisis in the Gulf is possibly also a reflection of the character of the 45th president of the United States. We have become so used to belligerent tweets emanating from the White House in the small hours that we are now inured to Donald Trump’s language. When he first came to office, Trump seemed a terrifying figure, likely to lash out at any moment with the full force of US military might. We cringed when he tweeted that he had a bigger nuclear button than Kim Jong-un. But the longer his presidency goes on, the more familiar we become with Trump’s methods. He likes to talk tough, as he did with the Korean leader, but his threats are really just a way of bringing adversaries to the negotiating table. Far from being the warmonger many supposed him to be, it is quite possible that Trump will complete his term of office without leading US forces into a new offensive anywhere in the world — something which would distinguish him from his five most recent predecessors.

Set against that possibility, however, is the President’s national security adviser, John Bolton, who continues to subscribe to the interventionist doctrines which drove George W. Bush towards a policy of regime change against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq — a policy which, in spite of showing the superiority of American military might in the short term, did not neatly end once victory was declared.

It is far from clear how the present Iran crisis will play out. For Britain, it may well be that a low-key approach to the spat between the US and Iran is the best policy for now. It was not our assessment that Iran had broken the terms of the international deal which lifted sanctions on the country in return for it agreeing to curtail its nuclear programme. We are still sticking to our side of the deal. But in the past few weeks the International Atomic Energy Agency has confirmed that Iran has once again increased its production of enriched uranium. Iran is still governed by a deeply untrustworthy regime. The country’s behaviour over the past few months, since the US withdrew from the international deal which ended sanctions, is not that of an innocent party committed to normalising its relations with the rest of the world. Rather, it suggests a government whose default position is to build up military might, riding roughshod over international accords and treaties in the process.

Before long Britain, along with other signatories of the 2015 deal with Iran, will be forced to take sides. Trump has announced that his next move will be to extend sanctions to those who trade with Iran — with the aim of cutting off all Iranian oil imports. We will have to decide between opposing Trump’s dismantling of the 2015 deal or joining the US in the imposition of sanctions on Iran. China, another signatory to the deal, will be forced to make a similar choice. If it continues to trade with Iran, the trade war between the US and China will intensify.

In four weeks’ time, Britain will have a new prime minister who will be immediately preoccupied with Brexit. Both of the candidates have experience at the Foreign Office but, having been in the job during periods of relative calm in the Middle East, neither will be prepared for the reality of having to deal with the latest chapter of conflict in the Gulf at the same time as trying to leave the EU. Both contenders would do well to prepare by spending some quiet moments over the next few weeks working out how they might respond to a US conflict with Iran.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in