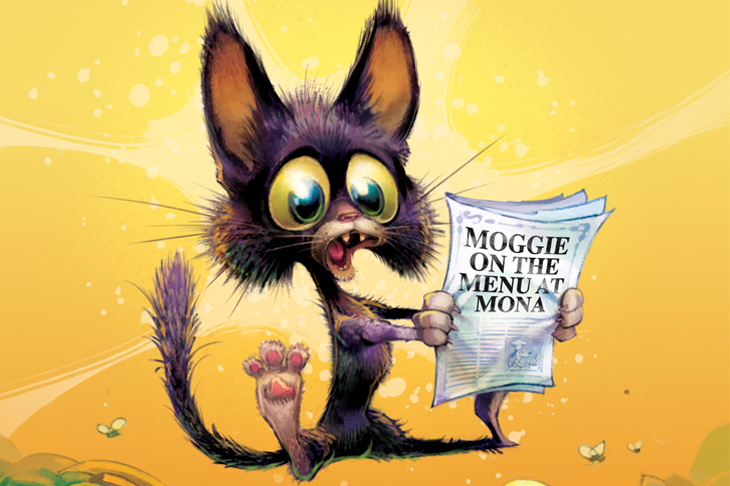

‘Would you like the cat consommé?’ The waiter passes me a spoon. I swallow the broth in one go, deciding that – when it comes to eating feline – fast is best.

I am sitting on the world’s largest glockenspiel deep underground at Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art, taking part in the very first of American artist Kirsha Kaechele’s Eat the Problem feasts.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in